Written by Rose Hoban

The first few years of the Formerly Incarcerated Transition (FIT) Wellness Program were limited to assisting people with mental illness who had recently been released from state prison in Wake County.

Evan Ashkin, a family physician at UNC Health who helped create the program in 2017, said FIT Wellness has been able to serve 45 to 50 people a year in this “very vulnerable population.” That meant helping them connect with psychiatric services, housing, and employment—providing services that would enable them to succeed.

However, the program's footprint was small. Nearly 20,000 people are released from incarceration in North Carolina each year.

Now, thanks to new funding from last year's state budget, FIT Wellness is poised to expand into Durham, Orange and New Hanover counties. Ashkin estimates the program can help about 200 people a year.

The expansion was announced in January by Gov. Roy Cooper as part of a “whole-of-government approach” to helping people transition out of the cancer system and back into society. The goal is to lower costs across the state by reducing recidivism and connecting these people to mental health care and other essential services.

“This is a very important initiative by the governor, setting aside $99 million for people with disabilities. [severe mental illness] They are affected by prisons and the genocidal system in general,” Ashkin said.

Mr. Ashkin will use the $5.5 million that will be paid to FIT Wellness from that stream to show how its approach will not only improve the lives of those in its care, but also reduce the current costs of keeping people locked up. We want to show that it can also save states money.

The funding going to FIT Wellness is just a fraction of the $835 million that Congress plans to spend over two years on behavioral health in 2023.

Those funds are beginning to be distributed, and state Health and Human Services officials plan to make a series of announcements over the coming weeks about how some of the millions of dollars will be spent.

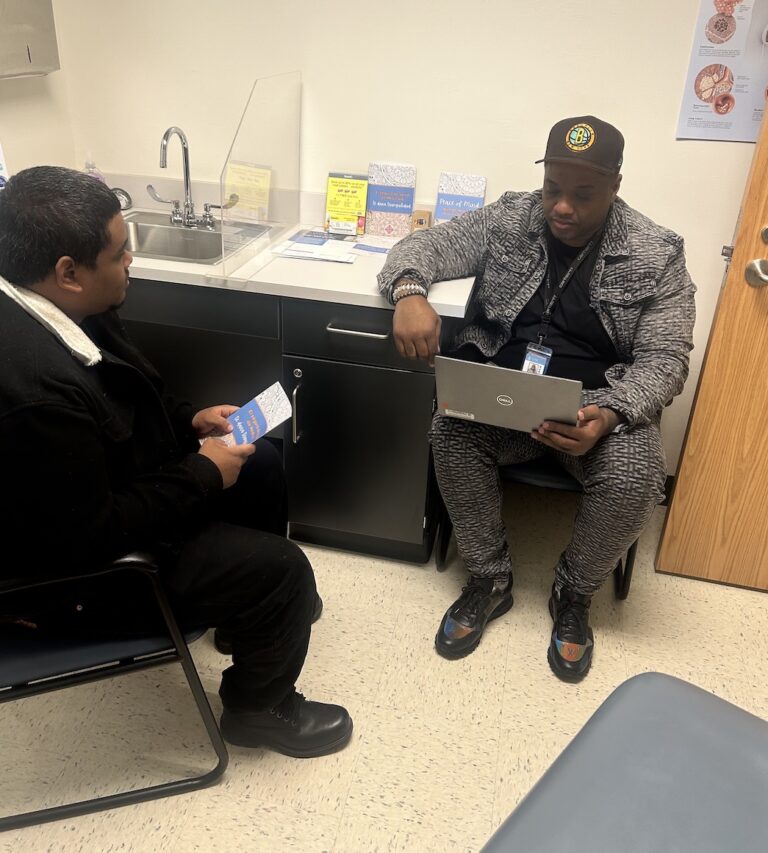

credit: Provided by FIT Wellness

Start

Kelly Crosby, director of the Department of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities and Substance Use Services, said during a legislative committee hearing Tuesday morning how the department plans to spend some of its allocated funds. It was previewed to members of Congress.

A portion of the funding will expand existing programs. Some renovate existing facilities for new purposes. Help the department reap greater benefits in North Carolina, which is still struggling with numerous behavioral health needs that have been underfunded for a decade and made even more acute by the pandemic. Plans are still being finalized.

One goal for the first year of the two-year funding stream is to get money into the system quickly.

“While 'shovel-ready' isn't quite the right word, we looked at facilities already available that needed renovation, projects that were already nearing completion, and locations with room to expand our facilities.” Crosby told the Health and Human Services Joint Legislative Oversight Committee.

“We're trying to think of infrastructure investments that are really cost-effective and efficient, things that can be started right away.”

Crosby compared the current behavioral health system to a crisis management system. For example, when someone calls 9-1-1 with a heart attack, they know the phone number, know that the paramedics in the ambulance will rush to pick them up, and that they will eventually go to the hospital. I am.

Crosby said the state's behavioral health crisis services are lacking in comparison. People looking for behavioral health services may know the phone number, but they don't know who will come to help them or where they will go once they arrive.

“We have the bones of this system in North Carolina,” she said. “It’s fragmented, inconsistent and certainly not well-funded.”

But things are slowly changing, she said. With the expansion of our 9-8-8 crisis line, more people know where to call. Currently, approximately 7,500 calls and text messages reach crisis responders each month.

The next step to getting help can be more difficult than punching in a 9-8-8, Crosby said.

“When I ask people, 'Do you know where behavioral emergency care is in your area?' Most people have no idea,” she said. “When I say, 'Do you know where the crisis center is? It's not an emergency room, it's a psychiatric crisis center,' and no one knows where it is.”

Even if someone knows about the existence of a behavioral health urgent care center, there's another hurdle, Crosby said. Some locations are staffed 24/7, while others are only open during business hours. Some places also offer detox services. Others don't. Some are set up to take care of children. Others are intended for adults only. Many of the facilities tend to be in large counties, leaving open space in smaller rural areas. Mobile crisis teams that visit homes to try to defuse mental health crises are becoming more common, but many counties have yet to create such a workforce.

It's inconsistent, Crosby said. Additionally, many people don't trust the facilities there, she added.

One of the projects putting the state on a path to more stability is converting some facilities in Butner, North Carolina, into crisis treatment centers for children and youth. Once the center is fully operational, it will free up some space at other state facilities that have been feeling cramped.

“We will be adding 44 new beds for children, 64 new beds for adults, nine new beds for behavioral health and critical care, and one new joint response team,” she said. . “This is a mobile crisis. Mental health and law enforcement are working together to respond.”

overlooking the road

Crosby said that in the second year of funding, DHHS will further address system-wide staffing challenges, including a shortage of 20,000 direct support workers who support people with mental health, developmental and intellectual disabilities. He said he would seriously consider the matter.

“We have an untapped resource. We have what we call 'peer support specialists,'” she said. “These are people with lived experience. They're certified, but they're not necessarily getting and keeping jobs in our system. And that's a real loss.”

Crosby and her boss, DHHS Undersecretary Mark Benton, discussed raising pay for nurses and others working in psychiatric hospitals. Currently, 296 (34%) of the state's 894 psychiatric beds are unavailable due to staffing shortages, Benton said.

“These are not easy jobs, but they are very meaningful jobs. So they need good rates,” Crosby said. “And we need to give employers the tools to keep people employed.”

Lawmakers pushed back. Rep. Hugh Blackwell (R-Valdez), whose district includes Morganton, home to the state psychiatric hospital Broughton Hospital, acknowledged the importance of offering competitive wages. But he cautioned that it may not be a panacea, as other providers have also increased pay.

“Everyone is chasing too few people.…What we need in the sector is fresh thinking…What exactly are we going to do about these regulations that are holding us back from hiring when there is a need?” Is there a need?” Is there someone standing in front of you? Blackwell said. “How do we deal with this ongoing payroll issue? How do we use the money we're paying now on a temporary basis to solve some of our payroll needs?”

Robin Whalen, CEO of Central Regional Hospital, said there is evidence that the $220 million salary increases approved at last year's general meeting are alleviating the shortfall to some extent. She told lawmakers that before the pay increase, it was difficult to hire mental health technicians, staff members who are required to be in the facility 24 hours a day.

“The rate of adjustment in the labor market this year has been great for us. It just came into force and I have already seen a medical technician. Last year in 2023, the number of hires was on average around two per month. , which has grown to more than 20 people in the past two months,” she said. “It had such a big effect.”

However, workforce challenges remain. When central regional facilities and other facilities are shadowed by larger health systems that pay better salaries, such as Duke University or UNC Health, state health officials can recruit and retain registered nurses at state salaries. I haven't been able to do that. An RN can make about $64,000 when he starts at a state-run facility, but he can make more than $100,000 at a large academic hospital or staffing agency, Whalen said.

Short-term expenses, long-term benefits

Crosby told North Carolina Health News after the meeting that the department plans to make an announcement about investments from the spending in the coming weeks. She said she's excited to see how spending on mental health services will be saved in the long run if the state continues to monitor carefully.

For example, it costs on average about $48,700 to keep someone in state prison for a year. In a best-case scenario, if the UNC FIT Wellness Program were to serve as many as 200 people per year, the state could save as much as $9.7 million per year in prison costs, which would quickly overwhelm the cost of funding the program. exceeds.

Ashkin noted that FIT Wellness will also help train psychiatry residents at UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke School of Medicine, as well as some residents in New Hanover County. He noted that residents tend to stick around where they train, which could be a side benefit of the program in states with shortages of psychiatric professionals.

“So when you give people exposure, they see how gratifying it is,” he says.