In north Denver, the city operates a reception center set up to manage the arrival of an influx of newcomers. Many of them are coming across the country's southern border due to dire economic conditions, political instability and violence.

Few people check in. A city worker sitting in front of a laptop asks questions in Spanish. He carries one or two bags, and some people roll them around. The walls are lined with boxes of donated shoes and clothing. Although the reason is not clear, traffic has decreased significantly.

“We don't have a lot of people here right now,” said John Ewing, a spokesman for Denver Human Services, adding that the city will accept 144 busloads of new immigrants in December 2023, many from Texas. He pointed out that he had been “What we were seeing a few weeks ago was 200, 300 people arriving in Denver per day. There was a line out the door, a line outside the building. There was a line.”

Ewing said there are still about 20,000 new immigrants living in the metro area, although that number has decreased. Some of that number of people will probably get colds and flu. Some people suffer from chronic illnesses such as diabetes or heart disease. Some are pregnant. There are also children. In addition to medical needs, these new immigrants also endured long and grueling voyages.

Now, Coloradans and the state's health care system are working to ramp up care for the number of new immigrants who unexpectedly increased last year.

This includes places where extra personnel strain staff and resources, such as doctor's offices and hospital emergency rooms.

A man who recently arrived at the welcome center explained through an interpreter that his name was Oscar and he was 19 years old. He was wearing a baseball cap, striped samba soccer shoes and was carrying several bags.

Oscar declined to give his last name, but said he was from Colombia.He traveled for three months by foot, bus, and train, including crossing dangerous jungles through Panama to reach the United States.

“Yeah, it was really tough,” he said. “Mui difficile.”

He came to Denver by way of New York. He said he was cutting his hair, showing a trimmer in his bag. He left his family in Colombia because Colombia was not safe. Now he said he wants to study and work.

If you don't work, you can't eat, Oscar said in Spanish.

Hart Van Denberg/CPR News

“They have come a long way.”

In the past 15 months, the city has seen 40,000 new arrivals. Many have moved elsewhere, but about half remain, putting a strain on services.

“By the time they get to us, they're completely exhausted,” said Dee Dee Gilliam, a public health nurse with the Denver Department of Human Health and Environment. “They are starving. They are dehydrated from the long journey.”

Gilliam said new immigrants will first be provided with food and water. New recruits then undergo a brief medical exam that includes important questions. 5,000 people have been tested so far.

“We’re looking for respiratory disease,” she said. “We're primarily looking for symptoms of coronavirus or influenza. The skin diseases we're looking for are Mpox, chickenpox and measles.”

So far, no cases of highly contagious measles have occurred. But Ewing, the DHS spokeswoman, said the city has recorded more than 600 cases of chickenpox in the past year or so, including 150 in January after a cold snap.

“With so many people in shelters and the cold weather not allowing everyone to come together,” he said. “It just makes it more likely to spread.”

Newcomers will be offered the option to get vaccinated when they arrive at the reception center, Ewing said. These include varicella, TDap, MMR, influenza, COVID-19, and meningococcal vaccines.

Ewing said that since January, health care providers have vaccinated 90 adults and 84 children at the reception center. First-timers can also get vaccinated at public health clinics.

Hart Van Denberg/CPR News

Mayor Mike Johnston said the city was facing a “tornado” due to the twin crises of homelessness and dealing with the arrival of new immigrants.

Supporting new immigrants cost the city more than $42 million. This is on top of the more than $48 million spent on the House1000 campaign to get more than 1,000 people off the streets and into shelters in late 2023, Denverite said.

In search of better medical care

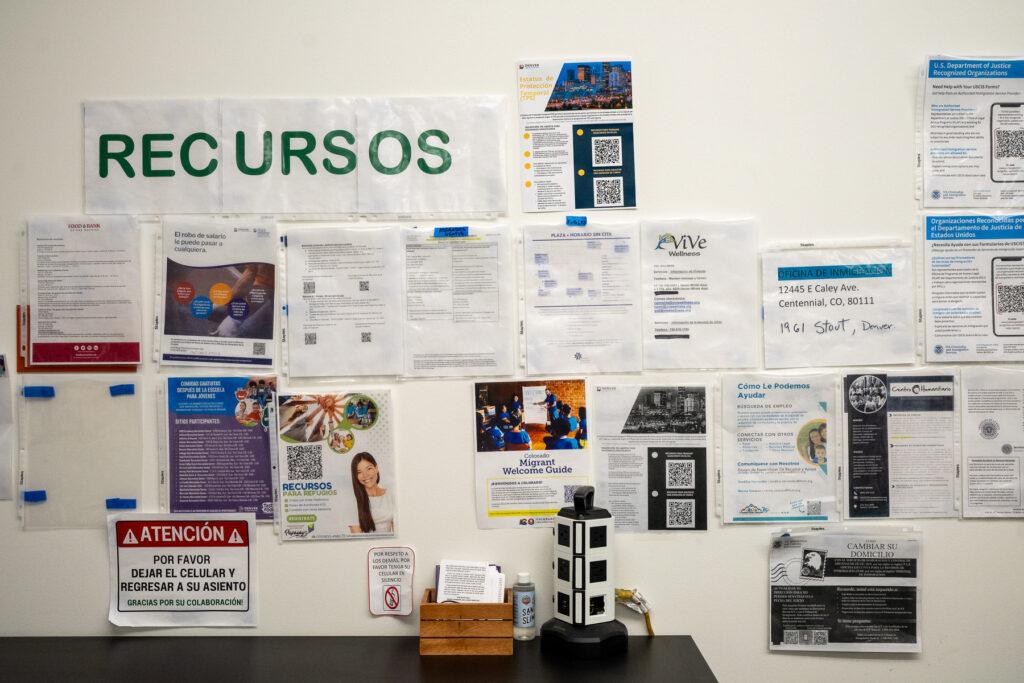

At the reception center, behind the tables where the nurses sit, there are pictures drawn by visiting children. Public health nurse Courtney Peters said some people come to the center with specific needs.

“Many of them are coming here seeking better medical care. And some of them have come by taking medicines at the border,” she said.

Hart Van Denberg/CPR News

In February, the ACLU, along with partners, reported that medicines and medical equipment are among the items Border Patrol routinely seizes when new immigrants cross the southern border.

Critically ill patients arriving in Denver are referred to emergency rooms, urgent cares and clinics.

“The number of patients has increased significantly. It's good that we have increased capacity with this new building,” said Tepeyac Community Health Center, which cares for newcomers and other underserved populations. CEO Jim Garcia said.

We recently built a new building, which triples our capacity. This was helpful as volumes and wait times increased. Dr. Garcia said the wait time for new uninsured patients has increased from about six to seven weeks in October to 12 weeks now.

In many cases, new patients who immigrate have no acquaintances in Colorado, are unable to pay, and government reimbursement is uncertain.

“They're coming with even less support and resources than the typical immigrant family,” Garcia said.

This sentiment is echoed by volunteers who work with new immigrants. Grassroots organizations are scrambling to provide food, clothing and transportation to new immigrants, many of whom are crammed into hotels.

“Oh my god, it's really, really difficult,” said Lydia Flynn, one of more than a thousand volunteers who stepped up to help. She said seven groups have formed, including NE Denver Community Outreach, of which she is a member.

Health care is a hurdle, she says.

“I was so worried about new moms. I actually met a mom the other day who was 37 weeks pregnant,” she said. “But she looked maybe four months old.”

Many newborns end up in pediatric intensive care units with low birth weights because of poor maternal eating habits, Flynn said, adding that many newborns also need help with their mental health.

“We have families affected by domestic violence, anxiety and a lot of depression.”

In late 2023, many children from warmer climates complained of cold and flu-like symptoms. Not knowing what to do, volunteers took the people to the Denver Health Center.

“Just to get basic medical needs. I mean, none of us are doctors, so the best thing we could do was go to Denver Health,” she said.

Further increase in patients

Denver Health is the state's primary safety net hospital. We care for patients regardless of their ability to pay. It's a big job these days.

“We estimate that we have seen approximately 8,500 patients from countries new to Denver,” said Dr. Steve Federico, a pediatrician and director of government and community affairs.

That was in 2023. As a result, his ER visits increased by 10% in the fall and early winter, putting even more pressure on the staff.

“In terms of where the tension is, that's really the story,” Federico said. “It's probably related to additional patients that we didn't have the staff or weren't scheduled to see.”

The demographics of new arrivals has changed over the past year from more young people to more families. At Denver Health, he delivered over 100 babies during that time, which is not surprising considering the number of people who visit Denver.

“It creates an additional moral conflict in that you think, 'Okay, what's going to happen to this family with a new baby in our community?'” Federico said. “At a time when, as the city regularly points out, it is becoming increasingly difficult to respond to the numbers in terms of social needs.”

And, of course, there's the economic cost: Treating those patients in 2023 will cost $10.5 million, Federico said.

The hospital provided a total of $140 million in free care in 2023. So hospitals already face rising costs and low reimbursement from government programs and will need to care for the new arrivals.

“I don’t see a path forward unless the public steps up significantly to provide funding to advance our mission,” he said.

Hart Van Denberg/CPR News

When I returned to the Denver Welcome Center, three more people arrived. Important documents were lost in transit and I had to deal with government documents.

Lorena, 37, who just gave her name, said in Spanish that she cleans houses and does nails. However, as Venezuela's economy plummeted, she left the country.

She tearfully explained that due to her financial situation, she had left behind four children, three teenagers and one 10-year-old. She could not afford to feed her family. She lived in a shelter and earned money by recycling her cans. After her arrival in Denver, she developed serious problems with her kidneys.

At the shelter where he was staying, he suffered from severe pain and had to be hospitalized. Lorena now needs to see her specialist, but she is worried about the cost, she said through her translator.

“She doesn't want to go again to see a specialist because she knows it will increase her debt to the hospital,” the interpreter said. Where did she go for treatment? “She went to Denver Health.”

Navigating both her health and medical costs will be an ongoing challenge for this new immigrant and the city in which she currently resides.