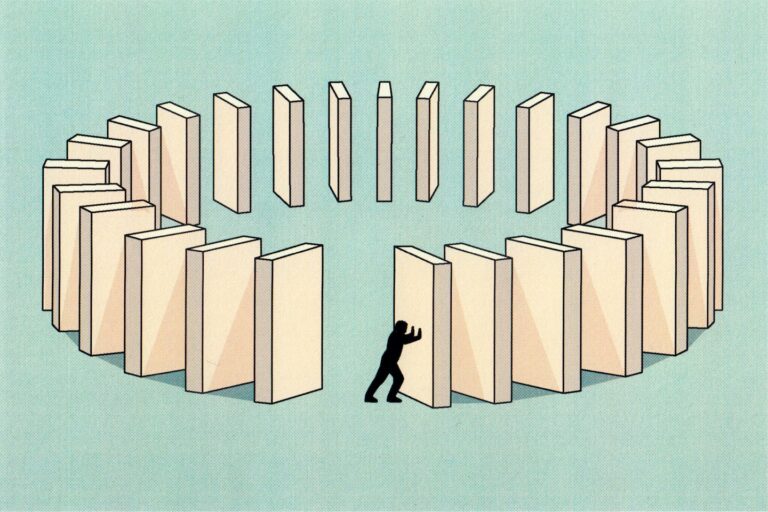

Self-destructive behavior often leads to stagnation, bad outcomes, and poor relationships. But with awareness and conscious effort, experts say it's possible to end the cycle of self-destruction.

an attempt to protect ourselves

Experts say self-sabotage can be the product of a variety of things, including low self-esteem, internalized beliefs, fear of change and the unknown, and an excessive desire for control. But underlying those reasons is the human desire for self-preservation.

We are wired to avoid threats and be motivated by rewards. Self-sabotage stems from an imbalance between our desire for threat and reward, says psychologist and author of Stop Self-Sabotage: Six Steps to Unlock Your True Motivation, Harness Your Willpower and Get Out of Your Own Way said Judy Ho.

“To protect ourselves from potential emotional and psychological stress, we slow down or stop moving in the direction we really want,” she said.

For example, procrastination may not be due to laziness or irresponsibility. Research shows that when a job is difficult or less rewarding, we are more likely to avoid it.

Anne Peck, 57, who was adopted as a child, avoided searching for a biological family because of the deep-seated trauma of feeling unwanted. Two months after his mother was diagnosed with frontal lobe dementia, Peck finally met his birth mother. They were together for less than three years, until her mother passed away.

“I got to know her and part of my story,” said Peck, who lives in White Bear Lake, Minnesota. She says, “But she couldn't have learned so much if I hadn't thwarted her idea of finding her family.”

Damage caused by self-sabotage

Shruti Mutalik, a certified psychiatrist, says she sees self-sabotage not only in her patients but also in herself, and that the main causes are feelings of worthlessness and fear of success. Mutalik once postponed applying for a full medical license and then again postponed renewing it.

Self-sabotage is not only detrimental to your level of success and achieving your desired results, but it can also be harmful to your mental health. “It can lead to self-deprecation and a lowered self-concept,” Ho says, making people less likely to take action to achieve what they want.

Self-sabotage is also associated with increased anxiety, increased risk of depression, and unhealthy ways of coping, such as using escapist strategies such as alcohol or drug use.

How to prevent self-destructive behavior

Many of us recognize that our self-destructive actions and inactions are harmful, but we still find it difficult to stop them. But experts say there is hope even in what seems like an insurmountable situation.

Approach your own struggles with compassion. Many self-destructive behaviors may have been helpful in the past, but they are no longer helpful. Treat yourself and your struggles with compassion.

Ellen Langer, a psychology professor at Harvard University, said that our negative behaviors often have a positive side. For example, a person who is perceived as gullible by others may consider himself or herself to be trusting, but because he or she emphasizes the positive aspects of that negative behavior, may find it difficult to change, she said.

“Every action, every action of people has meaning from the actor's point of view, otherwise the actor wouldn't do it,” Langer said.

Be aware of unhelpful thought patterns. “The next time you notice a negative emotion or action you wish you hadn't done, ask yourself, 'What was I thinking just before I noticed this feeling or action?'” Ho says. suggest. Once you become aware of your thought patterns, you can question them, modify them, or change your relationship with them.

Try labeling your negative thoughts. Start by saying, “I have the idea that…” Ho said. For example, you might think, “I'm afraid I'll end up alone.” This reminds us that thoughts are just that: “You don't have to believe your thoughts or believe them to be true,” she said.

Challenge self-destructive behavior. Mutalik, who had been delayed in getting his medical license, said his therapist asked him, “What does it mean to you to become a doctor and apply for a license?” Mutalik found himself worried that his professional identity as a doctor would be replaced by his personal identity. Over time, she came to see them as complementary. That, along with her therapy and other changes, led her to “prioritize her behavior over avoidance.”

Please be responsible. “We need to recognize the role we play in our own lives,” said Ryan Sultan, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry and director of mental health informatics and integrative psychiatry at Columbia University. .

“We have to accept the idea that sometimes we make mistakes. I think that's a prerequisite to understanding our own self-sabotage,” he said. “And some of us have a hard time acknowledging and taking responsibility for our actions in some way.”

Sultan said the way to change is to identify what you want, not what you want, and move forward. This is not easy, he said. “You have to find the motivation to change your life, and change is very difficult,” he says.

Start small and build on it. Sari Ingram, 40, a chess teacher in Tennessee, has battled addiction and other forms of self-sabotage. She has been sober for four years, and she said working on things in short order and breaking down her tasks into chunks helped.

The first time she had to get sober and work on a project, her 12-step sponsor said, “Just do it for five minutes.” That helped, she says. She says, “Because you can say to your brain, 'Look, this doesn't have to be like her 13-hour ordeal.'” Right. Just sit there for five minutes. ”

Choosing the things that are manageable, she said, “What can I undo?''

be patient. Ho said self-improvement takes time. “You'll notice small changes for the first few days, but it may not feel like new self-driving until a few weeks later, but that's to be expected,” she said. “Give yourself a little grace.”

Have questions about human behavior or neuroscience? Email BrainMatters@washpost.com I may answer that in a future column.