Suzanne Alexander vividly remembers a report about a St. Louis baby born with congenital syphilis.

Blindness, hearing loss, developmental delay.

Some were underweight. Some had bone problems.

That is if they survive.

Alexander, director of infectious diseases for the St. Louis City Health Department and a member of a task force studying the causes of Missouri's rising congenital syphilis numbers, said more than half of the cases he has investigated to date show an alarming trend. Stated. Outside.

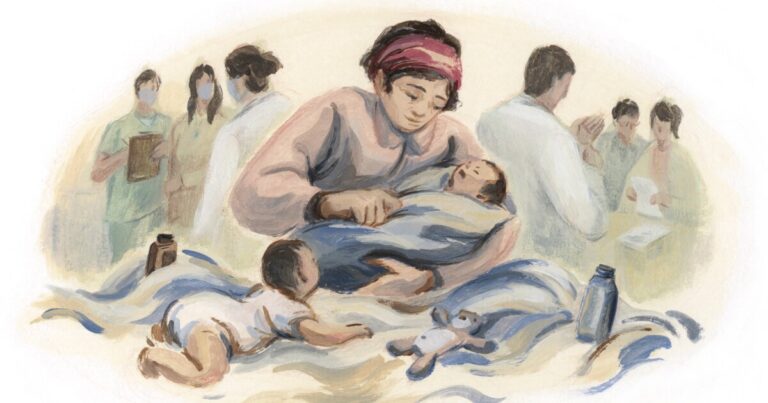

Mothers of babies born with this infection received little prenatal care.

State and national health departments have been sounding the alarm in recent years as cases of congenital syphilis increase and local health care workers are overburdened.

From 2017 to 2021, the number of congenital syphilis cases increased by 219% nationwide. Missouri saw a 593% increase, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

From 2012 to 2015, one stillbirth due to congenital syphilis was reported in Missouri. At least one infant has died every year since then, with 18 deaths reported from 2016 to 2022, according to the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services.

If detected early enough, the disease is reversible in utero.

Two bills introduced by Republicans in the House and Senate would create a system to further crack down on such incidents. The bill comes after the state health department issued another alert last week reporting that Missouri had recorded 81 congenital syphilis cases in 2022, the highest number in 30 years.

“This is an eight-fold increase in preventable disease,” the advisory warns.

Currently, only two syphilis tests are required during pregnancy: during the first trimester and at birth. The bill would add a third test at 28 weeks, when there is still time for mother and baby to be treated. The bill would also require third-trimester testing for HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B, which can cause liver damage in infants.

“We're sending a signal to providers that this is a very important service,” Alexander said. “And they have the support of Congress.”

What is congenital syphilis?

A mother can transmit congenital syphilis in the womb at any point during pregnancy.

In adults, symptoms include a rash on the palms and soles of the feet, hair loss, swollen lymph nodes, and pain. Often these symptoms go away on their own, but the disease remains.

According to the CDC, if a mother becomes infected within four weeks of giving birth and does not receive treatment, the infant has a 40% chance of dying at or shortly after birth.

“This bill is really about maternal and child health, making sure mothers get the care they need, and babies get the care they need,” said Spring, who proposed the bill. said state Rep. Melanie Stinnett, a Field Republican. He helped pass postpartum Medicaid expansion last year.

The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services partners with 180 sexually transmitted disease testing and treatment facilities across the state. The location can be found at: health.mo.gov/testing.

The test can be done during your regular appointment and does not require an additional doctor's visit. The cost will be covered by Medicaid.

Stinnett, who has a background in the medical field and is vice president of therapeutic services at Ark of the Ozarks, a nonprofit organization for people with disabilities in Springfield, said he believes the bill, which has bipartisan support, He said he has high hopes that the bill will be passed.

A similar bill was proposed by state Sen. Elaine Gannon, a Republican from DeSoto. The bill has had a committee hearing but has not yet been voted on.

“A healthy mother equals a healthy baby,” Gannon told the Senate Health and Human Services Committee on Wednesday. “This is just another step we can take to ensure our most vulnerable people have access to appropriate health care.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Missouri Center for Public Health Excellence testified in support of both bills.

Syphilis Trends in Missouri

Dustin Hampton, director of the state Department of Health's Division of HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections and Hepatitis, said he has seen a shift in the population most affected by syphilis over the past two years.

Hampton said that in the past, most cases of the virus were transmitted to men who had sex with men in urban areas. Therefore, for the past 15 years, much of the health department's education and messaging has targeted this group. But in recent years, cases have shifted to rural white heterosexuals.

In most of the congenital disease cases we have seen, women have had only one prenatal diagnosis or none at all.

“In many cases, the only care they received was when they arrived at the hospital to give birth,” he says.

Hampton said the bill would help quickly identify infected people, but would not prevent the spread of syphilis between sexual partners.

“People who are currently experiencing an increase in syphilis may not even realize they are at risk for syphilis,” he said, adding that they may not know they have syphilis until the day their child is born. She added that she had heard many stories from women who didn't know her. .

Hampton said the health department has started offering rapid syphilis tests at some laboratories so patients can get results within 20 minutes instead of waiting days.

The department has also established a statewide syphilis advisory group and is in the process of launching a congenital syphilis review committee. It also helped double the number of disease intervention specialists in public health agencies and county health agencies.

Treatment of syphilis during pregnancy requires three doses of benzathine penicillin G given one week apart.

A recent investigation by ProPublica revealed that some drugs used to treat syphilis are in short supply.

Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services spokeswoman Lisa Cox said the state has not experienced any shortages so far.

“We continue to receive regular shipments of Bicillin from our distributors,” Cox said. “We have maintained an adequate supply of medicines and encouraged health care providers to utilize shared decision-making for all those treating syphilis.”

A crisis that goes beyond STD testing

As lawmakers work on legislation, local governments in Missouri are facing deeper problems than just a lack of testing.

When investigating cases in St. Louis, where cases of congenital syphilis increased 11-fold between 2017 and 2021, Alexander noted how fewer women were receiving prenatal care and those with a history of substance abuse problems. I noticed how many there are.

“One of the challenges in this tragedy is that not everyone is testing for social determinants of health,” she says. “So we don't know what kind of support the mother will need to have the ability to proceed with treatment.”

The St. Louis Health Department is currently meeting with community-based organizations and people diagnosed with syphilis to learn more about prevention education and common barriers to treatment.

“There are very few successful cases of ignoring a problem,” Alexander said. “We are seeing the effects of lack of access, and we are seeing the effects of lack of access, and because we have not had proper medical care, we are living with lifelong illness and yet are unable to understand what the disease is like. We are seeing the impact of not knowing.”

In St. Louis, the largest increase was among black women. Ms Alexander said stigma was also a factor, as was not enough sex education in schools to make her partner more likely to use condoms.

“There's a genuine fear among women in general of being labeled as 'diseased,'” she says.

In a business session ahead of Thursday's Kansas City Council meeting, Dr. Benjamin Glynn, chief medical officer for the Kansas City Health Department, said the problem isn't that mothers aren't getting tested at their appointments, it's that they aren't getting tested. said. First of all, prenatal care.

He attributed this to social determinants of health, such as substance use disorders, housing insecurity, intimate partner violence, and lack of transportation. Ms Glynn also lost contact with her mother, who did not come for her full treatment despite her positive diagnosis, she said.

Kansas City has seen a 221% increase in syphilis cases among women since 2017. Many of those women were of childbearing age. As a result, the city has added sexually transmitted disease-related positions to the health department in hopes of more efficient contact tracing, especially after visitation at local sexual health clinics has declined during the pandemic. Added 5 people and 2 supervisory positions.

Tracy Russell, executive director of Nurture KC, said the nonprofit serves about 300 pregnant women and mothers of newborns in 14 of the metro's poorest zip codes and educates families about safe sex practices. He said he also supports education.

Mr Russell said a lack of knowledge about sexually transmitted diseases remained an issue. Some families don't know that they can have sexually transmitted infections during pregnancy, or that they may be asymptomatic.

“The message that always resonates most with pregnant women is the impact on the baby,” Russell said.

However, this does not guarantee good access to healthcare. Russell pointed to a lack of trust in the health care system, especially in communities of color.

“You can't underestimate the mistrust in the system…not having enough providers from these communities is also very problematic,” she said. “All these issues converge to produce this type of outcome.”

This article originally appeared in The Missouri Independent, part of States Newsroom.