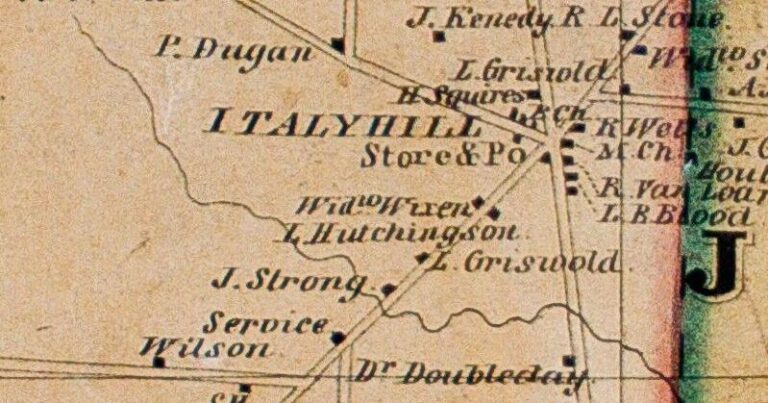

TThe town of Italy's two main communities have always been Italy Hollow (now simply called Italy) and the twin hamlets of Italy Hill, located around the intersection of Italy Hill Road and Pulver Road.

The populations of these communities were never large, but they have now decreased significantly. However, it was once a lively place. Each had its own school buildings, factories, taverns, hotels, shops, and churches. Of her two villages, Italy Hollow was a little larger and busier, but there was more coming and going for the residents of the hamlets, which were about three miles apart.

In the 1920s, Frances Bowen Curtis of Dansville, Livingston County, recalled: chronicle express About his childhood spent in the hills of Italy in the 1840s and 1850s. His anecdotes about school, church, and other aspects of life emphasized the closeness of the community. He particularly recalled one incident that occurred on the Italian Hill Turnpike, which still runs between the two sides.

In the years before television, telephones, and radio, news was slow to travel, especially in isolated areas like Italy. Entertainment and socializing were also restricted. When their schedules permit, men in small communities gather at the post office or local stagecoach stop (or wherever newspapers and letters might be read or shared) to listen to the news and gossip. They were known to play games and interact with their neighbors. Another correspondent, who also grew up on Italy Hill, wrote: “People at the halfway point gathered at the post office, waiting for their mail to be distributed.” The Italy Hill post office was combined with a general store operated by Luther Blood on Pulver Road.

So when a new mail route opened between Italy Hill and Italy Hollow in 1852, it was a big step. Italy already had a gentleman mailman named Chester Lamb who had a Plattsburgh-Penn route that ran through this area. Therefore, a new young man was appointed in charge of the Italy Hill – Italy Hollow route, on which he operates three flights a week. Mr. Curtis declined to name the new mail carrier in his article, but we'll see why in the future.

This new courier had become somewhat arrogant and arrogant, knowing that people in both communities depended on the mail for news and entertainment and looked forward to his arrival. He rode into town on horseback and cracked his whip. A little boy near the turnpike will feel that pain if he somehow stands near the mailman's route. He “used a big whip pretty harshly on young boys,” Curtis recalled.

During this time, it was common for postmen to be armed to ward off thieves, and it was also common for them to carry whips as weapons. These were not small riding crops like someone would use on a horse. Anyone who has read Laura Ingalls Wilder's Farmer Boy, a book about her husband's childhood in upstate New York in the 1860s, is familiar with the story of a schoolteacher's disarray of teenagers in a one-room schoolhouse. You remember when I used the whip on you. If used correctly, such a whip can cut meat or break bones. It's unclear if the whip the cantankerous postman used was this big, but it was large enough to strike the boys running off the street, making a cracking sound. “Many times the boys had to find the bottom rail of the (turnpike boundary) fence or they were whipped,” Curtis wrote.

counterattack

Boys in both settlements were alarmed by the postman's dramatic entrance with a whip at their expense. No one was seriously injured, but everyone was outraged by the use of this dangerous weapon. The boys met in a “war council” to decide how to deal with their common enemy.

Immediately after the “council,” six to eight boys armed with sticks stopped a young mail carrier on the Italian Hill Turnpike and managed to pull him from his horse. They put the mailbag on his back and forced him to carry it up the hill to town. Perhaps one of the boys was leading the bewildered horse. The postman was then made to promise never to use the whip again.

The reaction to the boys' actions was explosive.

Adults in Italy Hollow were furious, claiming that interfering with the mail was a federal crime and that the boys, or their parents, would get in trouble or even go to jail. More than a week has passed and no one has been sent to prison. However, about 10 days later, when one of the boys was sent to Luther Blood's general store and post office to make a purchase, a “strange gentleman” was there. In a small community, a stranger will stand out, and the boy noticed the guy. Brad, who happened to be teaching Sunday school to the boy, approached the boy and asked him to read out the incident with the mailman to the stranger. The boy told the stranger that the new postman had hit the boys with a whip and that they “couldn't take it anymore” and told him what they had done. The man “smiled many times during the boy's story.”

Curious about the stranger, the boy's father approached Brad the next day and asked about him and if he had any trouble with the mailman. Blood reassured him with a laugh. “No problem, your son cleared them all. A U.S. military officer was here and said he thought the postman got what he deserved,” Curtis recalled. Apparently, after being humiliated by the boys, the postman complained to higher ups, but he didn't get the response he had hoped for.

He learned his lesson. Mr. Curtis does not recall any further trouble with himself or his postal service in general. Although he was already in his 80s when he wrote this article, the little Italian boys who stood up for themselves were clearly a cherished memory for him.