From Queen Muse

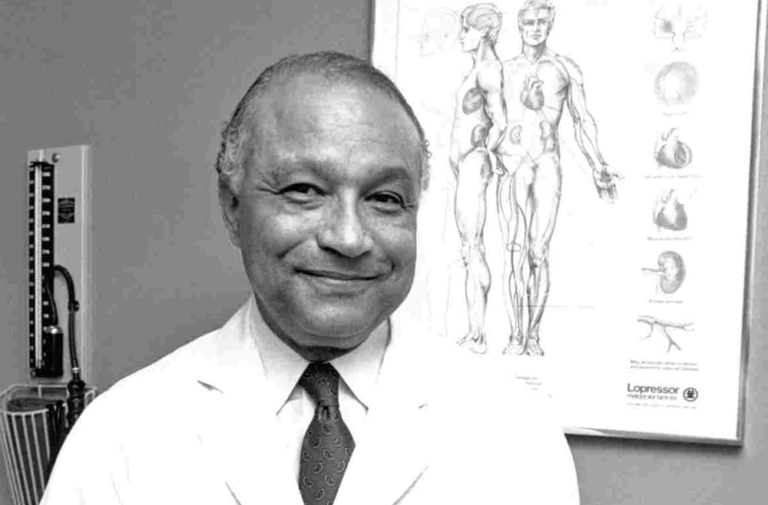

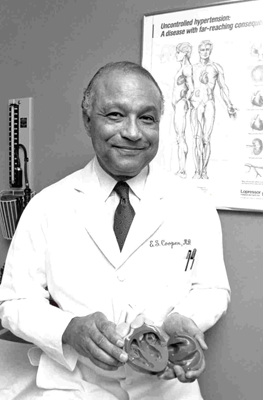

Edward S. Cooper's name adorns Penn Medicine's bustling internal medicine practice in University City. Patients who come in each day for a variety of routine care may not know the story behind the center's name, but they should. Dr. Edward S. Cooper is an accomplished Black physician and a living legend whose distinguished career is marked by numerous groundbreaking achievements in cardiology and health equity. Cooper, now a professor emeritus, served on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania for more than 40 years and as executive director of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania for 25 years. Mr. Cooper, who recently turned 97, announced plans to step down from his role. His influence and his story continue to resonate with former colleagues, new generations of physicians, and future physicians at the University of Pennsylvania and throughout the medical field.

A cardiologist with a sharp sense of purpose

Born on December 11, 1926 in Columbia, South Carolina, Cooper's medical journey began with a deep sense of purpose instilled in him by his parents, Ada Sawyer Cooper and Henry Howard Cooper Sr., DDS . His father and his two brothers were all dentists, and although Cooper took a slightly different path, he aimed to follow in their footsteps. After receiving his undergraduate degree from Lincoln University and graduating magna cum laude with his MD from Meharry Medical College, Cooper began his career as a cardiologist.

As the only black intern in his class at Philadelphia General Hospital, then a public hospital in the city of Philadelphia, Cooper witnessed numerous severe stroke cases, many of them black patients. This inspired him to want to make an impact in the field of heart disease and stroke. But midway through his internship, Cooper suffered a devastating battle with pneumonia, and at one point he thought he might not make it.

“I almost died,” Cooper recalled in an interview with NBC. “I said, 'Sir, if you get past this, I promise you that I will do something about this stroke problem, or at least make people aware of it and try to prevent it.'”

Cooper made good on his promise. He later co-founded and co-directed the Stroke Research Center at Philadelphia General Hospital. In 1958, Cooper joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and began providing internal medicine services and educating patients on stroke prevention through private practice at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

The driving force behind decades of stroke disparity discovery

Over the next 40 years, Cooper made seminal discoveries examining how racial differences affect stroke outcomes in Black people and other medically understudied populations. His research uncovered similar risk factors for stroke and coronary artery disease, such as high blood pressure and high lipid levels, drawing new attention to these common causes.

Kenneth Margulies, M.D., professor of cardiology at the Perelman School of Medicine, emphasized the importance of these contributions and said Professor Cooper's efforts to identify racial differences in protective factors for these diseases will improve public health and individualized health care delivery. said it helped mobilize responses to both of these challenges. . And they inspired Margulies to make similar contributions to the field in his own career.

Mr. Cooper made history in 1972 when he became the first black tenured faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. It wouldn't be the last of his breakthrough moments. In June 1992, Cooper became the American Heart Association's first black president after more than 30 years of service. He went on to chair the AHA's Stroke Council and the committee that produced the AHA's seminal scientific statement, “Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in African Americans and Other Racial Minorities.” I did.

Cooper later published a book. black strokeThis book is considered one of the first comprehensive publications on the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of stroke in Black patients. Today, Dr. Scott E. Kassner, director of the Pennsylvania Comprehensive Stroke Center, keeps a signed copy of Cooper's book on his desk. He says books and Cooper inspire his daily work.

“He dedicated his career to studying important issues related to the epidemiology, risk factors, and management of stroke in African Americans, with a particular focus on disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension,” Kassner said. Ta. “I'm currently leading an effort to improve the diversity of enrollment in stroke clinical trials. So while Ed and I didn't collaborate directly, his life's work has had a huge impact on my life's work.” There is no doubt that he gave.”

An inspiring person who connects the past and the future

Throughout his career, Cooper became a trusted physician and friend to civil rights icons such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the late performer and activist Harry Belafonte, but his humility also made him sought after. He told some interesting details that he would reveal. He has also used his influence to help his students, mentors, and fellow physicians maximize their impact.

“I'm just in awe of his career accomplishments,” said Gerald DeVaughn, M.D., clinical assistant professor of cardiology at Penn Medicine, who cares for patients at HUP-Cedar. “Each time, I am struck by his wisdom in humility and submission.” Although Devaughn did not have the opportunity to work directly with Cooper in the clinic, “it was a strange career opportunity that opened up for me. He doesn't know that I know he's a secret agent behind the curtain. I'm not alone. He knows that I know he's a secret agent behind the curtain. He has championed the careers of many doctors. Many are grateful for his guidance.”

Cooper's many titles and responsibilities sometimes made it difficult for him to spend as much time as he wanted with his wife, Jean Marie Wilder, who was also a doctor, and their four children. But Cooper's daughter, Dr. Lisa Cooper Hudgins, said she understood her father's work was important in more ways than one.

“He was a great father, but he was a busy father, so every moment of his vacation was precious,” said Hudgins, who also attended medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. “As a Black man in medicine, he knew he had to prove himself. He was 100 percent dedicated to treating stroke and hypertension. He truly felt this was his calling. I was there.”

The American Heart Association in Philadelphia recognizes Cooper's impact on the field by naming him its highest honor each year. Margulies became the recipient in 2022, followed by another Penn Medicine cardiologist, Paul J. Mather, in 2023.

Mather cited Cooper's influence and honor. “The more I learn about this man, the more I realize what an amazing person he is. He's a national figure and a hero to a lot of people,” Mather said. “What impresses me most is his grace and gentleness. When I sit next to him, I feel his intelligence and strength of action, but it is wrapped in gentleness and gentle grace. I just sit there and am in awe of him.”

Cooper, who has witnessed and contributed to decades of medical transformation, says medical school recruitment is the most important tool to ensure continued progress toward health equity. He pointed out what the AAMC report was. Turning around: Black men in medicine, found that more black men applied to and were admitted to medical school in 1978 than in 2014. Since then, growth in the number of black men admitted to medical school has been minimal. In 2021, only 5% of all U.S. physicians were black men

“We've been working on this problem for years, and in some ways it still hasn't changed,” Cooper said. “Getting students interested in science early on, starting recruitment in 10th grade, and creating opportunities for more Black men to enter the medical profession is a win-win for everyone.”

Today, Penn Medicine is investing in programs such as a partnership with the Philadelphia College of Physicians to help more young Black men enroll in medical school. The pipeline program offered has been expanded in 2022. Includes several Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

Cooper's advice to future doctors who will soon carry the torch is: “Work hard, study hard and strive for excellence.”