For Shawn Pleasants, the descent into homelessness wasn’t so much a plummet as an awful, incomprehensible slide. It was hard at first to even grasp the basic reality. “We lived in my Ford Explorer for a little over a year before I was willing to admit that we were homeless,” he said. That denial, he thinks now, was the only thing that kept him from panicking: “It was my protection.”

A Yale graduate with a bachelor’s degree in economics, Pleasants had worked as a Wall Street banker for several years before moving to Los Angeles in the late 1990s to start a small photography and filmmaking company. For a while, things went well: business was thriving, money was plentiful, and Pleasants bought a home in the city’s trendy Silver Lake neighborhood.

But then his company began to unravel amid disagreements with his cofounders, and, ultimately, it dissolved. At about that same time, in 2010, his mother died of cancer. The two had been close. Pleasants grew up in San Antonio, a bright kid in a loving family, one of four siblings raised by a teacher and an Air Force mechanic, and her death shook him. He felt lost.

After the business faltered, Pleasants figured he’d find other work or else rebuild his company. But neither happened, and when he was no longer able to pay rent on the house where he and his husband, David, then lived, they found themselves suddenly without a fixed address. “From this point on, I went through all my resources,” Pleasants recalled during a 2021 talk at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). “Because you’re scrambling. You don’t want to end up on the street, so you’re spending money as you have to.” Then, when the street becomes unavoidable, “you’re without any resources whatsoever.” Savings, social connections, friends and family: “You’ve exhausted all that.”

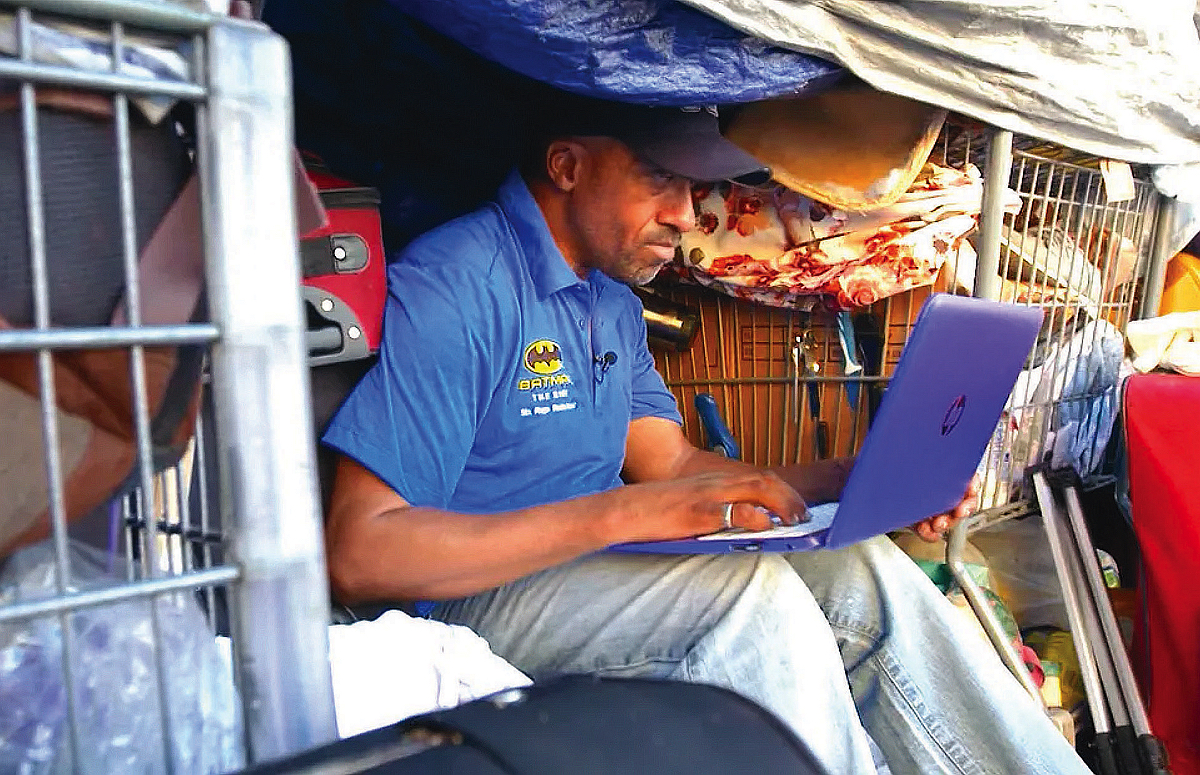

For a while, Pleasants and his husband couch-surfed; other nights they paid for a hotel. Eventually, they started sleeping in their car, moving from spot to spot, paying close attention to parking restrictions and street-cleaning schedules. But tickets piled up anyway (despite a clearly displayed handicapped placard) and the city impounded their car. Even then, as they moved their possessions into a tent in L.A.’s Koreatown, Pleasants held onto disbelief. “In your mind, you’re telling yourself, ‘It’s just around the corner, we’ll get things together and find another place. We just haven’t landed housing yet,’” he recalled in a recent interview. “I just had to keep that hope going.” He and his husband stayed for six years in their tent at the corner of 7th Street and Hobart Boulevard. By the time they had a roof over their heads again, they’d been homeless for nearly a decade.

“Everything in their life gets worse”

Every night, roughly one in 500 Americans sleeps somewhere public because they have nowhere else to go. They bed down in crowded shelters or empty buildings, parks, sidewalks, stairwells, subway tunnels. They sleep in their cars, or in tents by the side of the road, like Pleasants and his husband. Recent research finds homelessness is increasing among older adults; and longstanding structural racism means that people of color are disproportionately homeless. Black Americans are overrepresented more than threefold.

In 2023, amid skyrocketing rents, shrinking public assistance, an affordable-housing shortage, and the disruptions of COVID-19, the homeless population surged to 653,104, the largest on record. The number had been rising incrementally since 2016, but last year’s head count was a 12 percent jump. The increase was disproportionately high among the so-called “unsheltered” homeless, who now make up 40 percent of the total and are among the most vulnerable.

They are also the most visible. It is not uncommon today to see homeless encampments in American cities, some with tents and tarps stretching for blocks. This is especially true in places like California, where the need for shelter beds far outstrips the number available. Los Angeles has more than 46,000 homeless people but only about 16,000 beds. Washington’s King County, which includes Seattle, has 6,400 emergency beds for 14,000 homeless people. In Phoenix, where last November, city officials dismantled a massive encampment that on some nights accommodated 1,000 people, there are only half as many beds as homeless individuals.

Residents and business owners have reacted to the visible presence of the unhoused with increasing anger and impatience. State and local governments have tightened laws against loitering, panhandling, and camping on public property. Some go further: Kentucky’s state legislature is considering a bill that would allow people to use violence against someone camping on their land, and a city in Oklahoma passed an ordinance penalizing people who feed the homeless without a permit. This January, the Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments in Grants Pass v. Johnson, which could give governments much more leeway to clear out encampments and criminalize homelessness.

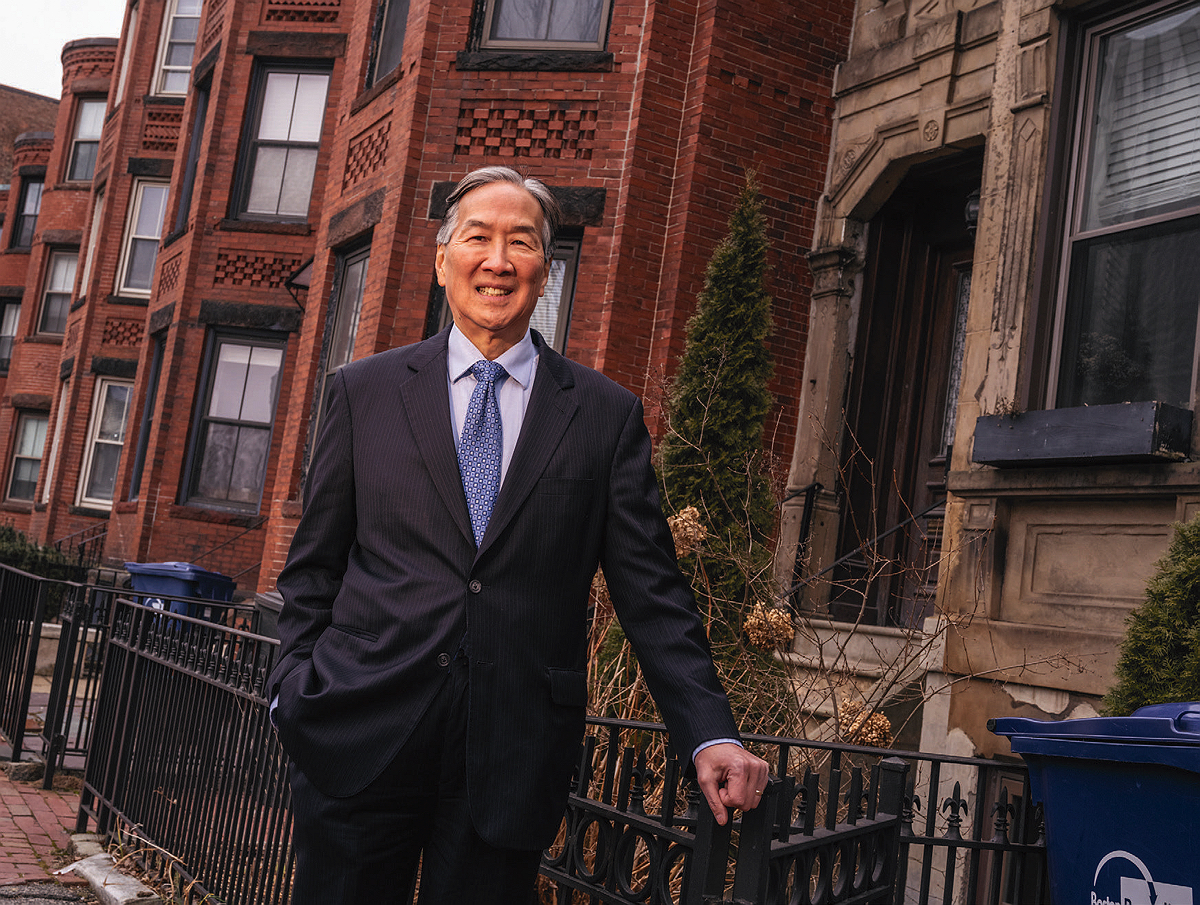

The need for answers has grown desperate. “Those encampments that are roiling communities from coast to coast—they are a very visible sign of the many systems failures that have driven this crisis,” said Howard Koh, Fineberg professor of the practice of public health leadership and faculty chair of the Harvard Initiative on Health and Homelessness (IHH), which launched in 2019 as an “academic home” for research and discussion on the subject. “Homelessness,” he added, “is undermining the very fabric of our society.”

Among those systems failures is public health. Amid the rising sense of emergency, it can be easy to overlook that homelessness is itself a devastating public health crisis, with ruinous, often permanent, effects on people’s lives. In a study published in 2018, Jill Roncarati, M.P.H. ’07, Sc.D. ’06, followed unsheltered homeless people in Boston for 10 years and found that their mortality rate was 10 times that of the general Massachusetts population. It was three times higher than for homeless people living in shelters The leading causes of death included cancer and heart disease. Being unhoused shortens life expectancy by decades.

Other studies reach the same grim conclusion. Roncarati, who works as a researcher for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), recently found that veterans without stable housing are 53 percent more likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or dementia. A 2023 report from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, focusing on older Americans, noted that many homeless people in their 50s and early 60s suffer from illnesses typically seen in patients 20 years older. Ryan Keen, Ph.D. ’23, a postdoc at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH), has found that childhood experience of housing insecurity is linked to elevated levels of anxiety and depression—nearly double, in some cases—and that link persists well into adulthood. Keen’s research, based on decades of longitudinal data collected in western North Carolina, also suggests that housing insecurity “embeds” itself biologically in children, elevating their inflammatory responses in a way that simple poverty does not. “Homelessness and housing insecurity get under our skin in a literal sense,” Keen said. Chronic inflammation carries a higher risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other conditions. “These are biological mechanisms,” Keen said, “that govern our health outcomes over the whole course of our lives.”

And a massive survey of California’s homeless population published last year paints a similarly searing picture. Led by Margot Kushel ’90, director of the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at the University of California, San Francisco, it is the deepest examination of American homelessness in more than 25 years. And because California is where nearly one-third of the nation’s unhoused live, the implications are national. Of the 3,200 homeless people Kushel and her team spoke to, two-thirds reported that they currently had symptoms of mental health issues, but only 18 percent had recently received nonemergency mental health care. Nearly half described their physical health as poor, and 60 percent said they had at least one chronic condition. The participants’ median age: 47. “Everything in their life gets worse when they lose their housing,” Kushel said: physical health, mental health, alcohol and drug use—“everything.”

“I couldn’t even cry”

Shawn Pleasants lost a tooth for every year he was homeless. His blood pressure, which went unchecked, spiraled so high that he developed cardiomyopathy. “And apparently, I had glaucoma,” he said. “I wasn’t aware.” By the time he saw an ophthalmologist, after moving off the streets, the pressure in his left eye was so high that the doctor said another couple of months delay would have cost him his vision. He had been diagnosed with HIV before becoming homeless, and for six years he stopped taking his antiretroviral drugs because, after his car was impounded, he had no place to secure the medications: in the tent encampment, they kept getting stolen. His only encounters with the healthcare system came during extreme emergencies: a severe bout of food poisoning, a case of pneumonia that hospitalized him for seven days. After a stranger stabbed him in the neck with a screwdriver, a police officer pulled it out, and Pleasants, in shock, was never taken to the emergency room.

“I saw so many things that a human should never see. I had never seen someone get killed before….I’d never seen someone starving….Things like that shake you to your core.”

And his mental health? “That’s a whole other ball game,” he said. “I saw so many things that a human should never see. I had never seen someone get killed before, I had never seen someone shot. I had never seen a woman being beaten in front of me. I’d never seen someone starving….Things like that shake you to your core.” He struggled with trauma, anxiety, depression. The shame and low self-esteem were sometimes unbearable. “I developed the mindset that I didn’t deserve help,” he said. “So when I would speak to my family members, my father and my brother, I would tell them everything’s OK, we’re just staying with friends. And meanwhile, I’m standing at a pay phone in the middle of the street in tattered and dirty clothing.”

The sweeps of his encampment carried out by the city’s sanitation department were devastating experiences. “When you first fall into homelessness,” he explained, “the things you have with you are directly from what I call your ‘real life’”—possessions that provide a tether to oneself. Pleasants kept family photos, medical records, medals from races he’d run, and his mother’s pearls. Then one afternoon, city workers came to clear out his encampment for the first time, and he lost everything. He remembers falling to the ground as the truck pulled away. “I couldn’t even cry,” he said. “Knowing that tomorrow I’m going to wake up with nothing from yesterday—it’s beyond naked, the way you feel.”

Over time, despair drove him to methamphetamine addiction. The drug provided a temporary escape, and it also kept him awake at night, which made it easier to fight off thieves and attackers. (Kushel’s research shows this to be a common phenomenon: 31 percent of the respondents in her team’s survey reported using meth to cope with homelessness. “People talked to us really plainly about how they couldn’t possibly stop using drugs until they were housed,” she told an interviewer at Vox.) In a roundabout way, it was addiction that led Pleasants back toward restoration: in rehab, he received therapy for the first time. “They twisted my arm,” he said: therapy was a requirement for getting through the program quickly. “But it changed me. It let the healing start.”

“It felt like an abomination”

All this sounds familiar to psychiatrist Katherine Koh, ’09, M.D. ’14 (Howard Koh’s daughter). She treats patients at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP), a nonprofit clinic founded in 1985 by a handful of clinicians led by James O’Connell, M.D. ’82 (profiled in “Street Doctor,” January-February 2016, page 58). Forty years later, BHCHP has grown into a network of 30-plus clinics tailored to the needs of homeless patients; it’s a fixture of the city’s medical landscape and a model for dozens of other programs around the country. As part of the organization’s “street team,” Koh delivers mental healthcare on foot several days a week to unsheltered people wherever they are. “I have one patient who loves to meet in a church basement,” she said.

She became interested in this work as an undergraduate, seeing people begging on the sidewalk in Harvard Square. “The juxtaposition of people living in abject poverty literally in the shadows of the richest university in the world really bothered me,” she said. “It felt like an abomination.”

When people ask her what it’s like to be a street psychiatrist, she tells them about the “long walk.” It involves patience and a kind of quiet doggedness; it requires the ability to maintain a posture of openness—sometimes indefinitely—with no guarantee that it will be reciprocated. Many of the homeless people Koh encounters on the street suffer from severe trauma, anxiety, depression, or a history of abuse, often dating back to early childhood. Some of them have had bad experiences with traditional healthcare. Often, they don’t want to talk. Koh keeps showing up. “The idea is to build trust and relationships over time,” she said. “We ask if there’s anything on their mind, and if they don’t want to engage, we kind of give them their time. And then, maybe, one day, you’ll get half a smile or half a wave. That’s progress, and you go from there.” The doctor-patient part comes later. “I have people whom I get to know literally for years before we do anything clinical,” Koh said. One patient she first encountered in 2015 finally walked into her clinic one day in 2022, wanting to talk. “Now he’s on a pathway to housing,” she said. “He’s working on his sobriety.”

She thinks a lot about the trauma she sees and how it leads people to homelessness. During a two-day conference last spring hosted by the Initiative on Health and Homelessness, Koh and other researchers and clinicians shared the stage with two formerly homeless patients who now serve on BHCHP leadership boards. “This is therapeutic for me,” Derek Winbush assured the audience at the start of his talk. He described growing up in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood and going to a school in the suburbs, because his mother (“a great person, God let her rest in peace”) wanted a better education for him. Back at home, he witnessed the violence of his mother’s abusive boyfriends—a shattering experience he couldn’t share with classmates on the school bus. “That’s part of my trauma,” he said. “I held a lot of stuff in.”

Sports was his outlet, until his outlet became alcohol and drugs, and by 18, he was on his way to state prison, where he spent four and a half years. “When I came home, I was a different person,” he said. He was dealing and taking drugs, and without a home of his own, he stayed in drug dens and other people’s apartments. At one detox clinic, during his first of a few journeys through drug rehabilitation, he was diagnosed with HIV. But he didn’t have the wherewithal to get treatment, so he put it out of his mind, and then in 1994, he found it had progressed fully into AIDS. By then, he had a child and was determined to live. He remembers a priest coming to his girlfriend’s home, where he was temporarily staying, to deliver last rites. “But I wasn’t ready,” he said. “I could hear my son crying in the other room.” He survived, somehow, until the “miracle drugs” arrived.

Joanne Guarino told a similarly stark story: abandonment by her mother when she was a child, sexual abuse by a family friend, early pregnancy, abortion, a boyfriend lost to overdose, addiction (though “drugs saved my life—I’d have killed myself otherwise”), and an accumulating list of daunting diagnoses. A tiny woman perched in a chair, with long auburn locks and a glass eye (the real one “I lost to the streets”), she tells a version of this story every year at Harvard Medical School’s white coat ceremony, with a tart humor that softens the details. “I know I joke,” she said at the conference. “I make everything funny, because if I don’t, well…” She trailed off into a smile.

“A complexity of need”

It isn’t only mental health care that is different for homeless populations. “You can’t simply pretend that homeless primary care is just regular primary care with homeless people,” said Stefan Kertesz, M.D. ’93, a professor at the University of Alabama Birmingham whose research and clinical practice focus on homeless patients. “If a person has no stable place to stay and lacks eyeglasses, then the medicines we offer can’t be dependent on a secure storage facility or require reading very fine numbers, like on a syringe for diabetes.” Often, the challenges go even deeper. A patient who is distrustful or distressed, or who’s been stigmatized by care providers in the past, usually requires more time and patience during a visit. “This extra time might go into focusing on a bunk assignment, as opposed to their blood pressure management,” he said. “And this extra time that we give to earn a patient’s trust looks to the healthcare system like inefficiency.”

“If a person has no stable place to stay and lacks eyeglasses, then the medicines we offer can’t be dependent on a secure storage facility or require reading very fine numbers.”

Kertesz has spent 15 years working to quantify what matters to homeless patients. “I always thought that the patient’s voice, if we could measure it, would redeem us and help us find the right path,” he said. He’s developed surveys to assess their healthcare experiences, asking about medical decision-making and the free flow of information with caregivers, as well as about respect and cooperation, trust and stigma, and doctors’ willingness to help patients find shelter or reschedule a missed appointment. His most complex surveys span dozens of categories. Kertesz’s research has demonstrated that programs like BHCHP and VA clinics tailored to the homeless deliver better care than mainstream medical practices; now he’s studying clinics across the country to identify the “active ingredient” that makes that care better.

Before coming to Alabama, Kertesz spent eight formative years as a staff physician at BHCHP; sometimes, he said, his current work feels like one long exercise in “proving that what Jim O’Connell”—BHCHP’s president—“showed me years ago is true.” Kertesz recalls one long-ago conversation in which O’Connell explained that what they were ensuring for their patients wasn’t access to healthcare—people could get access elsewhere—but quality. “It was the emotional work, the extra time, the outreach, the coordination, the advocacy,” Kertesz said. “Most of the work we did was good, but most of the work we did was not measured or valued by the mainstream systems.”

O’Connell remembers that conversation, too. Sitting in the momentary quiet of his office in BHCHP’s South End headquarters, a century-old building that was once a city morgue and now holds a 100-bed respite hospital, he said, “One problem with homelessness is that it suffers from a complexity of need.” At BHCHP, “We know the healthcare part of homelessness,” he said. “And we know the limits of what we can do. We can inch our way toward making it better. But homelessness is a whole university problem: it’s education, it’s law, it’s public health, it’s medicine, it’s policy, it’s architecture. Public health isn’t going to solve this by itself. Even housing isn’t going to solve it.”

That’s exactly the thinking that motivated Howard Koh’s initiative. He often tells a story about the brutal winter of 1999, when he was Massachusetts public health commissioner and 13 homeless people died on the streets of Boston. Those deaths, and the public’s shock and anger, deeply affected him. Later, he spent six years on the HSPH faculty and then served as assistant secretary for health in the Obama administration, before returning to Harvard in 2014, with homelessness still on his mind.

“Academia prides itself on taking on hard and complicated public health issues,” Koh said. There are thousands of researchers working on solutions to HIV and AIDS, cancer, heart disease, COVID-19, and climate change. But when it comes to homelessness, academia has been largely absent. Harvard’s initiative is one of only a few like it in the country, and Koh has established connections with a growing list of local and national organizations, as well as public officials; within Harvard, the IHH has built collaborations with entities including the Kennedy School, the Joint Center on Housing Studies, and the Advanced Leadership Initiative. O’Connell serves on the steering committee, along with Denise De Las Nueces, M.D. ’08, M.P.H. ’12, BHCHP’s chief medical officer and interim CEO. A new course, “Homelessness and Health: Lessons from Health Care, Public Health, and Research,” taught by Roncarati and Maggie Sullivan, Dr.P.H. ’19, draws students from multiple fields. At IHH events and in interviews, Koh talks about the need for a “coordinated, systems approach” to homelessness. “Look, there’s lots of good people trying to respond to this,” he said, but overall, their efforts remain largely fragmented and isolated. “And vulnerable people keep falling through the cracks.”

Much of what needs to be done is already known. Last year’s survey of California’s homeless population by Margot Kushel’s UCSF team offered numerous recommendations that echo those of previous research: increased access to mental and medical healthcare, vastly expanded rental assistance programs, and tax credits to incentivize the construction of affordable housing. For the chronically homeless and those with complex behavioral health issues, the report called for more permanent supportive housing that follows a “housing first” approach, which offers people a place to stay without requiring that they first accept treatment. Studies, including by Kushel, show it can be remarkably successful in keeping people housed.

But it isn’t a simple proposition. “Housing first isn’t housing only,” Kushel said during a talk in March at the GSD. “We will not solve this problem by denying the enormous trauma that people who’ve experienced homelessness have been through.” Supportive housing must provide needed services such as intensive case management, regular psychiatric and medical care, and assistance with employment and job skills, education, transportation, legal issues, family supports. Housing first “was always supposed to be a clinical intervention” as well as a housing one, said Kertesz, who coauthored a 2016 paper on the subject with Kushel and O’Connell. “People need good supports,” said O’Connell, who has seen some patients finally get a roof over their heads, only to flounder and end up back on the street—or worse—without the services they need. “Housing has been like a miracle,” he said. “But what brought them to the street in the first place doesn’t go away just because they’re through the threshold.” In some cases, the “furies,” as he has called them, intensify once someone is alone in a studio apartment.

A few dramatic success stories suggest a way forward. Since 2009, the federal government has reduced homelessness among veterans by half, using a combination of rapid rehousing and permanent supportive housing. The VA has some built-in advantages, including a national integrated health system that can establish standards and enable continuity of care for patients when they move; it also screens each person for homelessness or housing instability and can connect them quickly with resources in the Department of Housing and Urban Development and organizations in local communities. “This initiative demonstrated that you could have a big interagency collaboration to get people the housing they need and the case management to help them sustain it,” said University of Pennsylvania social scientist Dennis Culhane, who helped design the initiative and has studied homelessness for decades. “And it demonstrated that a national commitment to solving a problem works. But you need political will.”

Since 2011, Houston, the country’s fourth most populous city, which once had one of the highest per capita homelessness rates, has reduced its unhoused population by 60 percent, moving more than 25,000 people from the street into houses and apartments, using housing first principles. As with the VA, the effort has involved coordination and data-sharing. Houston city officials convinced scores of public agencies, local service providers, corporations, and charities to work together.

These efforts cost money. The VA’s homelessness initiative required a federal budget increase from $400 million in 2010 to more than $1 billion in 2016. The policies that researchers advocate would cost federal and state governments billions of dollars. But homelessness is already expensive. Culhane calculated that nonprofits spent about $11 billion annually in today’s dollars on emergency shelter and transitional housing. Researchers at Brown University estimated in 2019 that the federal government spends roughly $2 billion every year on emergency shelter and transitional housing. Those figures don’t include excess health care costs (homeless people turn up in emergency rooms more often and have longer average hospital stays and higher readmission rates) or account for the costs to parks, libraries, sanitation departments, fire departments, police, and the legal system. Homelessness, Culhane said, afflicts the whole public sector.

Into Practice

During her talk at the GSD this spring, Kushel said, “Every route toward an answer flows through housing, and flows through building a society that is less unequal and less cruel.” At Harvard, efforts are underway to put programs into practice that align with recommendations from researchers. The Government Performance Lab (GPL) at the Kennedy School—one of the IHH’s partners—recently waded into the homeless crisis. As part of an initiative focused on prevention and rehousing, Harvard graduate fellows arrived last August at four U.S. sites, to spend 12 months helping to launch public interventions while analyzing what works (and what doesn’t), and what could be applied elsewhere. “The 800-pound gorilla in the room is that we need more deeply affordable housing,” said Carin Clary, the GPL’s director of homelessness and housing. “But that’s decades in the making. And so, our technical assistance is focused at this point on trying to figure out: What are the ramps where people are getting connected to housing? And how do we optimize this very precious resource of existing affordable housing?”

In Chicago, where city officials discovered 20 percent of permanent supportive housing units were empty, GPL fellows are helping to reduce move-in delays and simplify cumbersome eligibility requirements. In Los Angeles, where homelessness among Latinos rose an alarming 32 percent last year, the task is to understand why and identify gaps in services for Latinos.

Other projects concentrate on prevention. Last year, Detroit launched a hotline for people who are homeless, or on the brink, to call for information or help. It grew out of a similar program developed after COVID-19 hit to bring residents pandemic-related information. The new hotline is still a work in progress, but an ambitious effort to create a one-stop alternative to the jigsaw of phone numbers and aid organizations that typically confront people in an emergency.

GPL fellows are working with Colorado officials to prevent people from becoming homeless after they leave prison. Like aging out of foster care and discharge from the military, this transition is one when people are especially at risk of homelessness. The department of corrections is developing housing plans for prisoners six months before their release, tailoring workshops on housing services, screening for homelessness risk, and providing follow-up support as needed.

“The hardest thing—the hardest thing—is trying to predict who will become homeless. I think that creates a lot of immobilization for jurisdictions. Like, ‘How do we invest in this?’”

“The hardest thing—the hardest thing—is trying to predict who will become homeless,” Clary said. “I think that creates a lot of immobilization for jurisdictions. Like, ‘How do we invest in this?’” The pie never seems large enough, and those who are already homeless need help, too. “So, especially in times of scarcity of resources, it’s important to be able to show that investment in prevention is going to have a very direct outcome,” she said.

Clary speaks from experience. Before Harvard, she spent nearly 20 years in the “daily human emergencies” of homelessness response, working in New York City government and the mayor’s office to triage the needs of an unhoused population that, at nearly 93,000 people, is the largest of any American city. Under pressure like that, it’s hard to make time for innovations, even essential ones. The GPL fellows’ work is intended to be a “demonstration project” that doesn’t just suggest the next step but helps governments take it.

In the end, a fluke of luck and kindness pulled Pleasants and his husband out of homelessness. In 2019, a CNN reporter visited their encampment and aired a story on his unexpected encounter with a Yale-educated entrepreneur who had fallen on hard times. Among those who saw it was another Yale graduate, Kim Hershman, an attorney in Hollywood who was one year ahead of Pleasants in college and remembered his face. She searched out his tent in Koreatown, sat down next to him, and asked, “What do you need?” That began his journey back: through rehab and therapy to housing and health and something like “real life.” Now co-chair of the Lived Experience Advisory Board for the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority and a member of several other boards and committees focused on the crisis, he advocates for homelessness policies and HIV research. He also works in addiction recovery, “to reclaim some of what I lost.”

He’s housed and happy now, but his time on the streets did lasting damage. There are good days and bad days—sometimes he feels unstoppable, and at other times it can be difficult to get out of bed. “I still carry all that stuff with me,” he said. “It’s a long road back to yourself.”