Lifestyle

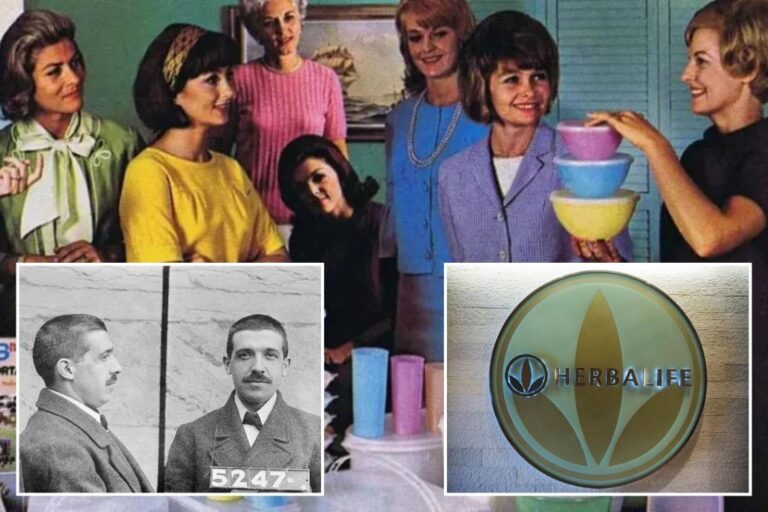

Tupperware is one of the most well-known multi-level marketing schemes in the United States, promising big rewards but often bankrupting its followers. A new book details how the industry came to dominate much of America.

Getty Images

When Julie, a 23-year-old college graduate, is invited to a “girl's night party,'' the guests are offered a large sum of money by a woman named Shawna from a company called Pure Romance who sells “bullet vibrators and vibrators'' to middle-class suburban housewives. I was told that I could earn money. Dildo,” Julie was about to start.

All she had to do was purchase one of four Pure Romance Starter Kits for $99 to “demonstrate and sell” and give it to friends, neighbors, strangers, her mother, and even herself. All he wanted to do was sell the company's “sex toys” to himself.

Even better, as Shauna explained, you can make real money by “recruiting” other women to buy the Pure Romance Starter Kit and have them become your saleswomen just like her. It means that you can do it. That way, when Julie signs her new hire, she instantly receives a “bonus” and that new hire becomes part of Julie's own “employee team” and her “downline” allows her to You will earn a lot of money.

Over the next six months, Julie will spend hundreds of dollars adding Pure Romance items to her sales kit.

But Julie's get-rich-quick dream quickly turned into an expensive nightmare. Despite her promises of big money, she, like countless other women, was lured into one of America's oldest business scams, a pyramid scheme. Financial independence and abundance of wealth.

In her new book Selling the American Dream (Atria), Jane Murray writes, “Most of the money is made in recruiting fees and from retailers stocking their shelves; It doesn't matter what product you have.”

An award-winning journalist and podcaster, Marie exposes the dark underbelly of a billion-dollar industry that feeds primarily on working-class women struggling to make ends meet.

“Some multilevel marketing companies, known as MLMs, don’t sell any products at all,” Marie explains. Instead, they're selling “an opportunity to learn how to sell, an opportunity to learn how to sell to people who might not even be interested in learning how to sell,” Marie explains.

Think Amway household products, Avon skin care, Mary Kay cosmetics, and Tupperware food storage containers. “Whatever the name, they all basically work the same way,” the authors assert.

Marie, a former high school dropout, said these pyramid marketing companies enrich only those at the top and impoverish desperate people who may fall for the impending wealth sale. For many, the end only comes when these questionable financial relationships destroy their finances.

There is nothing new about pyramid schemes. Since 1919, just after the end of World War I, an Italian-American named Charles Ponzi founded a company that promised investors a small fortune within about three months of investing their cash. Shady businesses have been operating smoothly across the United States.

Early investors doubled their money, just as Ponzi had planned. The hype soon spread, and overnight Ponzi was reportedly collecting $1 million a week from people who wanted to get rich. However, his fraud was discovered. He soon became bankrupt. He was later found to have been conducting fraudulent land deals in Florida, after which he was jailed.

Twenty years later, a California vitamin company appeared, selling supplements door-to-door with great promises of opportunity and wealth. The company called itself Nutrilite.

Nutrilite, an early proponent of branding and optics, cleverly recognized the power of image creation and told its sales reps to wear lab coats and carry clipboards “if they wanted to give off a doctor vibe,” says Marie. is writing.

Still, they claimed that they had a panacea for all troubles. However, the Food and Drug Administration investigated the false claims and ruled that the company could only state that it is “effective against a specific disease.”

Nutrilite still exists today, the authors write, and is sold by Amway, “the brand most responsible for the rise and proliferation of modern MLMs.”

Today's pyramid schemes are much more sophisticated, and involve the richest and most powerful people behind the scenes, as Murray reports in her exquisitely detailed research into the industry and history. She cites the power involved in a company called Herbalife as particularly representative of the influence of the people behind these companies.

For example, when Vice President Kamala Harris was California's attorney general in 2015, she refused to investigate allegations that Herbalife was a pyramid scheme. As reported, the lawsuit could have been successful, but it remains unclear why she did not file suit.

What is known is that at the time, her husband, Douglas Emhoff (now known as The Second Gentleman), was employed by the law firm representing Herbalife. You know the rest.

A similarly shady business circle surrounds Madeleine Albright, who served as Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton and became a brand ambassador for Herbalife. Critics allege that the company was suspected of operating a fraudulent pyramid scheme. Despite this, Albright made a whopping $10 million from the company between 2008 and 2014.

Betsy DeVos, who was appointed U.S. Secretary of Education under President Donald Trump after donating about $82 million to the Republican Party, is a majority shareholder in Amway, while her husband Dick DeVos Jr. He is the CEO of Amway, and his father co-founded Amway. 1959.

In 1979, when the FTC investigated Amway as a pyramid scheme with the “ability to deceive” new employees by dangling the carrot of financial freedom, Amway tried to avoid being publicly labeled a fraud. promised to thoroughly review its business practices.

“Amway currently leads all MLMs in global annual revenue with $9 billion and approximately 3 million resellers,” Murray said. The runner-up is Avon, with annual sales of about $3 billion.

According to a report detailed by Murray, Donald Trump purchased a personal MLM in 2009, before becoming president, and renamed it the Trump Network. He sold it in 2012, but before that he was marketing vitamins and supplements through vulnerable employees. Trump also made $8.8 million promoting American Communications, which is also considered an MLM.

The way MLMs continue to lure underdogs who should know better by now is the promise of millions of people. “Despite all evidence to the contrary, the dominant narrative of MLM is one of abundance and freedom from financial stress,” Marie writes.

Whether it's a stay-at-home mom, a person with a disability, or an immigrant looking for work, “people can lose their life savings and have their dreams ruined when they get involved in an MLM.”

The Consumer Awareness Association states, “99% of those who participate do not earn any money; lose money. “

However, the authors argue that the promise of great wealth continues to tempt new employees, who continue to borrow money to survive and stockpile products to peddle to new employees. “Instead of simply paying a commission or wages to sell a product, as in traditional retail,” Marie writes.

In Julie's case, she signed up to market sex toys and build her own female sales force, only to discover that the “exclusive” sex toys the company was promoting were actually available on Amazon for a third of the price. Marie said she quickly found out it was for sale. . So her income was less than her minimum wage, and she ended up with about $4,000 worth of questionably expensive products.

“The reality is that 99 percent of people who participate in MLMs lose money,” Marie concludes. For that 1%, they sit atop a towering pyramid that penalizes everyone else.

Load more…

{{#isDisplay}}

{{/isDisplay}}{{#isAniviewVideo}}

{{/isAniviewVideo}}{{#isSRVideo}}

{{/isSR video}}