Planters are parked and growing weather won't be an issue for months, but most farmers have already put together some kind of marketing plan for their 2024 crop — even if it means Even if it's just the idea of ”selling when the price is high.”

Indeed, given unprofitable new crop futures, it may seem premature to actually begin such a plan. However, seasonal weakness in corn and soybeans presents an opportunity in February for companies using call options to manage risk, according to Farm Futures' long-term study of preharvest sales. .

Options weren't the big winners in the study, which tracks results back to the 1985 crop year, when put and call trading resumed after a decades-long ban. In fact, on average, the option strategy is the least profitable of the methods evaluated, and combines are sold less often during harvest than other sales methods. Alternatives include selling futures or arrival hedge contracts, or using average price tools available with many elevators and some brokers.

More profitable strategies are likely to earn higher profits. However, if production declines sharply or if futures prices rise after a sale, the market could reverse. Options provide the right rather than the obligation of futures trading, which can reduce its volatility. This feature provides additional incentives for growers.

The downside to the option's efficiency is that its cost, or premium, must be paid in full upfront and is ultimately lost if the market rises. And not all options are created equal. A put, which provides the right to sell a futures contract, increases in value when the price falls, so it becomes more costly when the price falls. February could be a good time to start buying, as calls that convey the right to buy futures will be cheaper.

fare becomes worse

Three main factors affect option premiums:

-

time. Typically, policies that provide longer coverage periods have higher premiums.

-

Strike price. In-the-money options that can be exercised immediately for a profit have more “intrinsic value.”

-

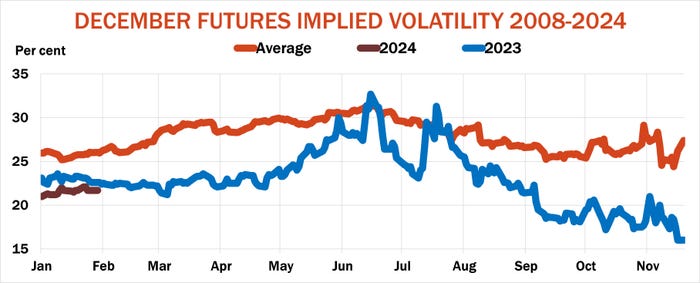

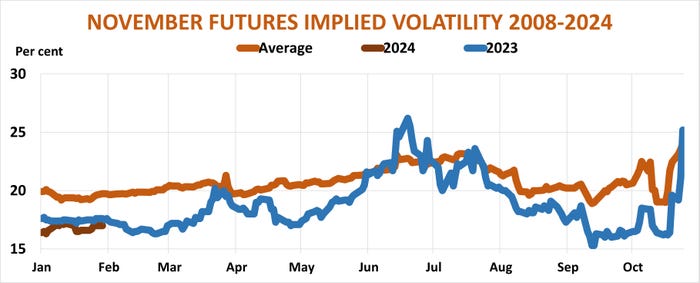

Implied volatility. As uncertainty increases, those who sell options to buyers, such as farmers, face greater risks. Implied volatility measures this uncertainty and typically increases during the hot summer months, especially during periods of weather markets. Therefore, sellers demand higher premiums for the insurance price they are offering.

The increased costs associated with buying February calls well ahead of expiry could be offset by both volatility and typically lower futures prices.

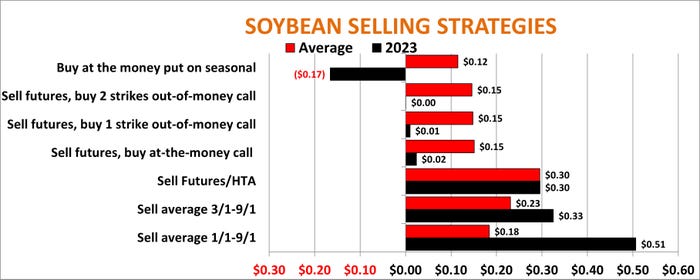

Combining call ownership with a sales contract is known as a synthetic put because it mimics the performance of other types of options. In farm futures research, puts continue to be the worst performing for both corn and soybeans. This is because the cost of risk insurance is higher during the growing season when futures prices may be higher. Corn puts were profitable over harvest prices only half of the time during the study period, and soybeans fared even worse.

In contrast, if you call to buy during a seasonally weak period (end of February, end of April, end of May) to protect a slightly delayed sale, the long-term return that option theory should claim is higher. became. Selling December corn futures/HTA that is subject to an “at-the-money” call, which is the right to buy the futures at the price at which it is trading, yields approximately half the profit as compared to selling the futures outright. It was done.

This calculation did not apply to soybeans last year. The synthetic put strategy barely lost money on November soybeans, while the at-the-money puts lost an average of 17 cents.

time of the season

At the time of the 2023 harvest, crop prices were low, a far cry from the previous year's prices of corn at $8 and soybeans near $18, due to inflation and the effects of the war in Ukraine. But some growers sang a different song if they followed proven seasonal patterns and built hedges throughout the summer.

The sale of corn in late June and soybeans in mid-July pushed prices $1 per bushel higher than yields for both crops, easing the pain of the market downturn suffered in the second half of the year.

It was no coincidence that we targeted these windows for action. On average over the past 50 years, December corn futures peaked in the fourth week of June, and November soybean prices peaked three weeks later, ahead of a critical period of regeneration.

In fact, 2023 follows the scenario documented in the Farm Futures study, which looks at sales during the second week of April and third week of May in addition to the summer period. The average of these gains from selling futures or hedge-to-arrival cash contracts relative to harvest was consistent with long-term results. Corn yields averaged 13 cents per bushel in the 11 locations surveyed, and soybean yields averaged 30 cents per bushel in nine markets around the Midwest.

This study compares futures and options strategies using spot price and options data to provide as realistic an assessment as possible, changing harvest dates at each location depending on the progress of the combine. To do.

winner

Of all the strategies, the average price tool was a surprise winner for soybeans. Using the average price from January through August, the contract was 51 cents, 21 cents higher than the average of the three sales made on futures/HTA, and slightly higher for corn.

Farm location was also important for the 2023 crop. States with above-average yields tended to have a lower-than-average yield base, while states with disappointing yields were forced to raise prices to meet buyers' needs. The spot market was strong. This created something of a “natural hedge” and helped equalize returns.

Click the link below for complete research results for all years and locations.

2023 Corn Results

Corn Results 1985-2023

2023 Soybean Results

Soybean performance 1985-2023

Central Illinois: corn | soy

Central Indiana: corn | soy

Cincinnati: corn | soy

Denver: corn

Evansville: corn

Garden City, Kansas: corn | soy

Kansas City: corn | soy

Minneapolis: corn | soy

North Central Iowa: corn | soy

Omaha: corn | soy

Toledo: corn | soy