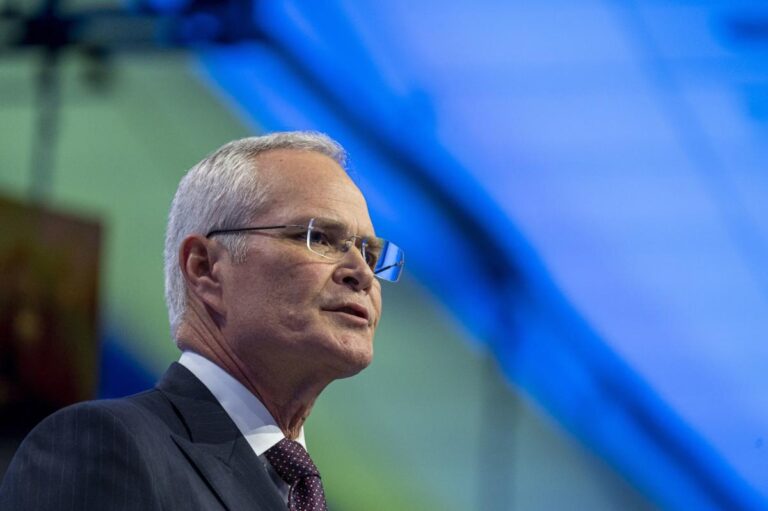

(Bloomberg) – After coming under fire from both environmentalists and investors during the first half of his seven-year tenure at the helm of Exxon Mobil Corp., Darren Woods is on the offensive.

Most Read Articles on Bloomberg

Woods has already filed an arbitration case this year against Chevron Corp. for trying to buy into Exxon's large offshore oil project in Guyana, as well as a lawsuit against investors demanding the company reduce emissions. Just a few months ago, he agreed to a $60 billion takeover that would make Exxon the largest U.S. shale producer.

Woods has also taken a tougher stance on climate change goals in speeches and interviews, saying fossil fuels will be needed for years to meet energy needs and that the world will reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. They claim that they are not on the path to. I don't want to pay for a cleaner alternative.

The message may be controversial, but it resonates on Wall Street. There, ambitious environmental, social and governance commitments run counter to the need for safe and affordable energy, and 'ESG' is fast becoming a hated moniker. Exxon is up 89% since losing a proxy fight to No. 1 climate engine in 2021, more than four times the S&P 500.

It's a stunning turnaround from the pandemic era, when Exxon posted its biggest losses in its history, employees left in droves and a shareholder revolt forced Mr. Woods to replace a quarter of the board. Exxon's resurgence symbolizes the resurgence of the U.S. oil industry, which now supplies 40% more oil each day than Saudi Arabia, forcing OPEC and its allies to retreat.

“It wasn't that long ago that it seemed necessary for the industry to take a green approach to attracting capital,” said Jeff Will, senior analyst at Neuberger Berman, which manages about $440 billion. It's not about that,” he said. But Russia's invasion of Ukraine “flipped a switch and made energy security more important. Exxon benefited because it never retreated from its traditional business.”

Fossil fuels will be in demand for decades to come, and not just by large corporations, but by governments and consumers, as Woods takes center stage at S&P Global Energy Conference CeraWeek in Houston this week. This will further strengthen this long-held view. Oil must pay for a meaningful transition to greener energy.

This is an unpopular argument for those who hold Exxon and Big Oil to blame for decades of delays and misinformation on climate change. However, it was created from the standpoint of increasing financial strength.

Exxon paid out $32 billion in dividends and stock buybacks in 2023, the fourth-most in the S&P 500, and has pledged to pay even more this year. The pending $60 billion acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources makes it the country's leading producer of shale oil and puts it at the top of an industry largely responsible for OPEC+ losing market share to the United States. I will stand.

Exxon also operates one of the world's fastest-growing large-scale oil developments in Guyana, making it the largest crude oil discovery in a decade and recently building a number of refinery and petrochemical expansions. Completed.

Its mega-rivals are now racing to catch up.

Chevron agreed to buy Hess for $53 billion, primarily to acquire a 30% interest in Exxon's Guyana project. But Exxon claims the deal was an “attempt to circumvent” a deal that gave it a first right of refusal, and is taking the dispute to arbitration at the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris.

Meanwhile, Shell and BP, under new CEOs, are now putting more investment money back into oil and gas after their share prices fell on the switch to renewable energy.

Greg Buckley, a portfolio manager at Adams Funds, which manages about $3.5 billion including Exxon stock, said Europe's biggest companies are struggling to convert high, steady cash flows from fossil fuels into profitable products. This shows the dangers of replacing renewable energy with low energy consumption.

“ESG has been popular, but ultimately I think return on equity is more popular,” he said. Shell and BP “found it the hard way.”

Dan Yergin, vice chairman of S&P Global, which organizes the CERAWeek conference, said the shift away from ESG terminology is a recognition that the energy transition is complex and will not play out in the same way in every region of the world. interview. Conflicts around the world, including in the Middle East and Ukraine, have highlighted the need for reliable energy supplies, but investors remain focused on returns, he said.

“Energy companies have shown discipline in capital spending and have responded to investors,” Yergin said. “You can see it in their spending, and the social contract between companies and investors has been renewed.”

Woods has also learned from his own experiences with activist shareholders. In January, the company filed a lawsuit against U.S. and Dutch climate investors who buy shares to promote emissions reductions. Exxon said in its lawsuit that the process of obtaining ballot votes at company meetings is “ripe for abuse by activists with minimal equity stakes and no interest in increasing long-term shareholder value.” said.

Woods has also become more vocal about his views on a low-carbon future. “The dirty secret that no one talks about is how much this is going to cost and who is willing to pay for it,” he said on a recent Fortune podcast. The world has waited “too long” to consider all the solutions needed to reduce emissions.

The comments drew anger from environmental activists.

“Exxon is particularly vulnerable to this move as it is most involved in efforts to slow the progress of climate change,” said Andrew Logan, senior director of oil and gas at CERES, a coalition of environmentally conscious investors who invested $65. That's infuriating rhetoric.” We manage trillions. “They have a long history of over-promising and under-delivering on low carbon.”

In a statement, Exxon spokeswoman Emily Mir refuted Logan's comments. In addition to its $4.9 billion acquisition of Denbury, the company announced it is pursuing more than $20 billion in low-emissions investments from 2022 to 2027. The acquisition gives the oil giant the largest network of carbon dioxide pipelines in the United States. These pipes are key to capturing carbon from highly polluting facilities such as refineries and chemical plants.

“Facts that don't align with uninformed bias are often frustrating,” Mir says. “That doesn't mean they're wrong. Someone needs to tell the truth about what it will take to achieve a net-zero future.”

In November, Mr. Woods also used the slogan of Exxon No New, a long-running environmental campaign that accused company executives of ignoring warnings from their own scientists since the 1970s that carbon dioxide causes climate change. I tried to flip the script. Exxon has denied intentionally misleading the public about global warming.

“We have the tools, the skills, the scale, and the intellectual and financial resources to bend the emissions curve,” he said at the 2023 APEC CEO Summit in San Francisco. “That's something ExxonMobil knows.”

However, the energy transition remains a major challenge. Concerns that oil demand could peak as early as 2030 have investors downplaying whether Exxon and its peers will be able to maintain dividends and share buybacks as the transition takes hold. Currently, the S&P 500 index is dominated by tech stocks, whose returns are expected to be more resilient in the coming decades.

Despite its rise over the past few years, Exxon is only the 17th largest company on the S&P 500, with a P/E ratio of 12.2x, 42% below the index average. Even though the US has become the world's largest oil producer, energy stocks account for less than 4% of the index.

“Exxon and the industry have yet to demonstrate how they will generate cash in a carbon-constrained future,” Logan said.

—With assistance from Naureen S Malik.

Most Read Articles on Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg LP