Several years ago, Andrea Mackey, MPH, was working in diabetes management and education at the International Pre-Diabetes Center in Los Angeles as a community health worker — a trained specialist with lived experience who helps patients in underserved communities navigate the health system and connect to social supports. In addition to helping patients with diabetes, Mackey recalls introducing them to mental health, employment, and housing agencies. “Sometimes it wasn’t the diabetes,” she said. “They were really struggling to pay rent, get proper food, or pay for their medication.”

Mackey found it gratifying to know she was improving the lives of patients, many of whom came from the Filipino community, like herself. But she was also frustrated by the limited resources at her disposal. “There’s only so much you can do, and you only have so much time,” she said.

Defining the CHW/P/R WorkforceA community health worker (CHW) is a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served. A promotor/a (P) is a trusted person that empowers their peers through education and connections to health and social resources. They largely work in Latino/x and Spanish-speaking communities. The R stands for community health representatives (CHRs), who do similar work in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. CHCF’s use of this abbreviation and inclusion of CHRs is shifting. As of April 2023, we added CHRs to honor the important role and long history of CHRs in the US and California. |

So Mackey was thrilled when she was able to apply her practical experience to the development of state policy to formally recognize this frontline health work done by thousands of people like her. Now a senior policy

manager with the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network (CPEHN), she helps lead a grassroots coalition focused on strengthening the integration and sustainability of community health workers, promotores, and representatives (CHW/P/Rs). “It’s really been exciting for me,” said Mackey.

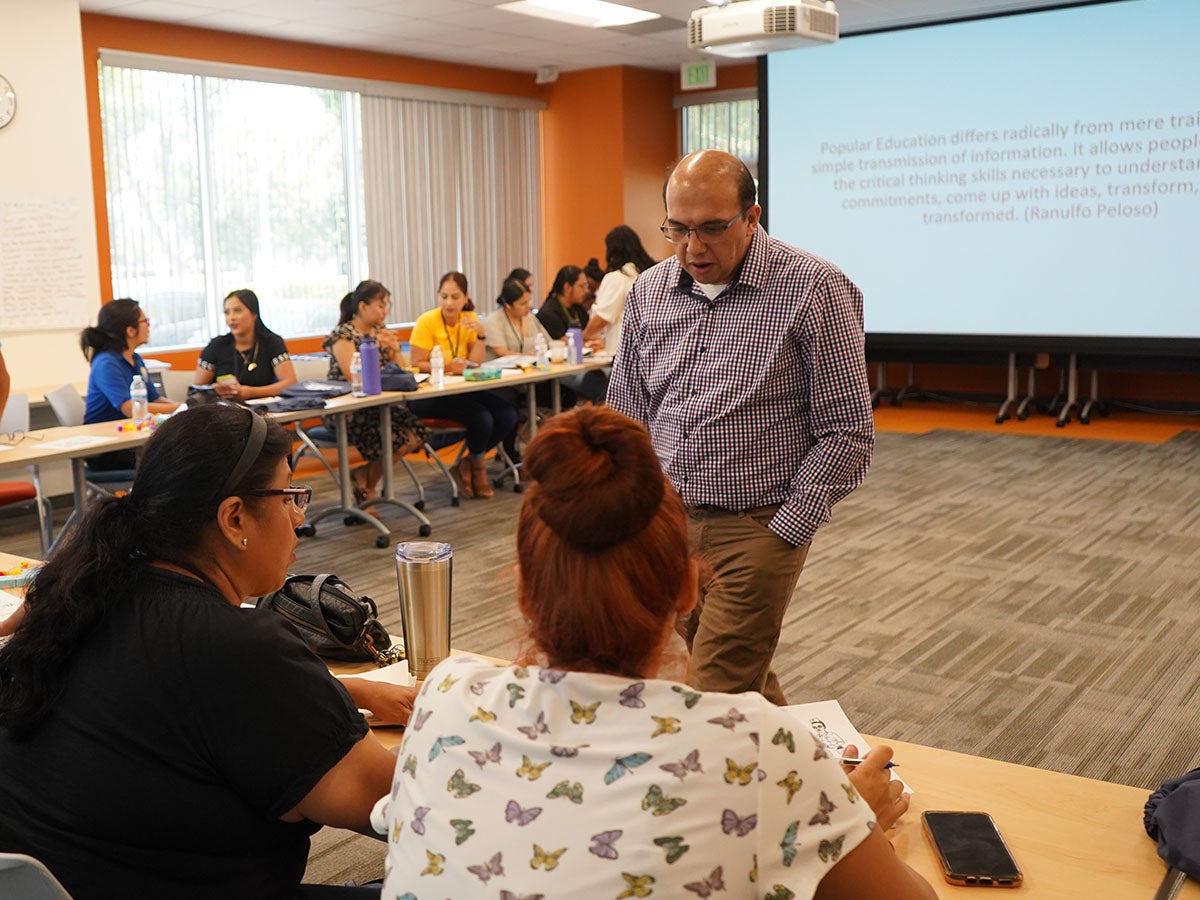

This is a transformative time for the CHW/P/R workforce in California. For generations, CHW/P/Rs have filled critical gaps in California’s health landscape and acted as liaisons between marginalized communities and mainstream systems. As trusted community representatives, they share cultural and linguistic backgrounds with their clients, many of whom are immigrants, people of color, and people with low incomes. And they provide accessible information and support in ways that resonate with their surrounding community.

“Having community members to lead these conversations with others in the community means we can find solutions to the problems, versus someone on the outside telling you what to do,” said Alex Fajardo, MCP, executive director of El Sol Neighborhood Educational Center. El Sol pioneered CHW/P/R training programs in San Bernardino and Riverside Counties.

Overcoming the Language Barrier

In communities where people speak languages other than English, being able to effectively communicate with a representative is exceedingly valuable. “A major barrier for accessing services in the ANHPI (Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander) communities is the language barrier,” said Doreena Wong, JD, policy director at Asian Resources Inc. (ARI), a community-based organization founded in Sacramento to meet the needs of Asian immigrants. It can be hard to keep up with demand — especially in communities with different cultural and linguistic subgroups. The supply of culturally and linguistically competent CHW/P/Rs must increase to meet that demand, she said.

For years, community advocates have stressed the need to bolster the CHW/P/R workforce, which has been shown to improve health outcomes, lower health care costs, and advance the cause of health equity. “The need for more culturally and linguistically appropriate, responsive care is a big issue,” said Cary Sanders, MPP, senior policy director at CPEHN. “A promising strategy that we’ve known about for a while is to really lean in and integrate community health workers.”

Now, California decisionmakers are joining the growing number of states in which leaders are embracing the vast potential of the CHW/P/R workforce, proposing new initiatives that seek to increase the awareness and use of their services, which will in turn improve health equity across the state.

Envisioning Community Health Work as an Accessible Benefit

Chief among these developments is the establishment of CHW/P/R services as a benefit for enrollees of Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program. Administered through the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), the benefit was implemented in July, 2022.

“The state is committed to ensuring equitable access to quality health care for all Californians, and increasing the use of CHW/P/Rs is an essential strategy to achieve this goal,” said Darci Delgado, assistant secretary, and Dan Torres, chief equity officer at California Health and Human Services (CalHHS), in an emailed statement.

Delgado and Torres explained that under the new policy, enrolled Medi-Cal providers submit claims for services provided by CHW/P/Rs who meet qualifications laid out by the state. Medi-Cal members can receive referrals for free access to such services as oral health education, domestic violence prevention, and chronic disease management.

The benefit fits into the state’s larger vision of maximizing health care quality and health equity in Medi-Cal by bridging health and social services, especially in underserved communities, said Palav Barbaria, MD, MHS, chief quality officer and deputy director of quality and population health management at DHCS.

“From a quality and health equity perspective, we recognize that the current health care delivery system is fragmented,” Barbaria said. “It really is designed around the needs of the care system and payers and providers, and not necessarily the experience of the needs of the members.”

Across the state, community leaders were thrilled when they heard the news in July 2022 that CHW/P/Rs were finally getting much-deserved recognition and a pathway to sustainable financing. Fajardo, who advocated for the benefit for nearly a decade, was excited to know that there was “funding to support the workforce.” Wong said she felt relief after having relied for years on grants and donations to support her organization’s CHW/P/Rs.

Mackey was encouraged that the benefit included a wide range of services. “It’s pretty broad on what can be encompassed,” she said. “We have health education that can be reimbursed, advocacy, navigation, social support. So we were pretty happy with how it landed.”

Virginia Hedrick, MPH, executive director of the California Consortium for Urban Indian Health (CCUIH), hopes the benefit sparks more advancements for CHW/P/Rs around the state. “It’s a policy win,” she said.

For Pooja Mittal, DO, chief health equity officer at Health Net, the benefit speaks to a positive shift in how the state views and approaches health. “It’s an incredible way to be thinking about what health care should be,” she said. California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) — the initiative within which the CHW/P/R benefit is rooted — marks a “revolutionary” step forward, Mittal said.

Building a Lasting CHW/P/R Workforce

Despite early enthusiasm about the benefit, however, there have been some bumps in the road when it comes to its implementation and adoption by health plans, community-based organizations, and Medi-Cal members.

“Uptake has been lower and slower than we would have desired,” said DHCS’s Barbaria, pointing to workforce development, billing support, and referral infrastructure as factors that have likely curbed momentum. Closing those gaps is critical to ensuring that CHW/P/Rs are woven into the fabric of Medi-Cal as a resource that can be accessed easily by people who need their services.

“We need to think through how they [CHW/P/Rs] are working with the nurses and doctors and nurse practitioners, and others in the health care ecosystem, so that we’re not just creating yet another silo,” Barbaria said.

Everything we do, especially when it’s new, takes time — and this is truly a paradigm shift.

—Rene Mollow, California Department of Health Care Services

Community-based organizations agree. Transitions Clinic Network is an organization focused on improving health care access for people returning to the community from incarceration. The network has made it a top priority to train CHW/P/Rs, many of whom have experienced incarceration themselves. “We want our patients to have the best health that they can get and, so, of course, there has to be training,” said national program manager James Mackey, MSW, DHSc.

“The state is committed to identifying, scaling, and supporting best practices and ensuring CHW/P/Rs are trained and employed to work with a wide range of populations,” said CalHHS’ Delgado and Torres in their emailed statement. “It is important to remember that whenever DHCS adds a new benefit, there is always a ramp-up period to add new providers and for member utilization.”

Certification Program Debated

Although nothing has been set in stone, there have been discussions about the state supporting a certification program that would elevate the image of CHW/P/Rs in health care settings while increasing awareness of CHW/P/R services. However, the merits of certification are still under debate. The state recently had to pause the development of the state certificate process to address important questions and concerns raised by the community. They plan to resume a more robust stakeholder process later this year.

Some community leaders anticipate that offering state-sanctioned certificates will “raise the level of credibility and professionalism” of CHW/P/Rs and help them to be “considered more part of a medical team,” said ARI’s Wong.

“It gives legitimacy and recognition to the field. It really starts setting up the conversation of . . . what a career pathway would look like for a community health worker,” said CPEHN’s Mackey. “At the same time, there is a tension that comes with the idea of certification, and many of us are asking why we need to legitimize ourselves when we have been serving the community well for years.”

Arianna Antone-Ramirez, health policy analyst at CCUIH, has witnessed how the lack of a formal career ladder has hurt CHW/P/Rs. Her mother is unable to afford her own apartment despite having been a community health representative for decades in the Bay Area. That might not be the case if she had been offered a clear route toward promotions, increased responsibility, and incremental income growth, Antone-Ramirez said.

Health Net has focused on workforce development since well before the Medi-Cal benefit was introduced, said Mittal. Ongoing education and upward mobility are necessary for CHW/P/Rs to see their roles as “a viable long-term career that offers growth opportunities as well as the opportunity to upscale in areas they are really passionate about.”

Minimizing Hurdles, Maximizing Incentives

Another limitation to the benefit’s uptake, community leaders say, has been the administrative burden of familiarizing themselves with and navigating the Medi-Cal system. Many community-based organizations have struggled to find the resources to ensure claims are processed and reimbursements are received timely and accurately.

For DHCS, that barrier has not gone unnoticed. “We’re thinking through how we provide better technical assistance…because those pieces are so critical,” said Barbaria.

In the meantime, groups like the San Diego Wellness Collaborative (SDWC) are stepping in as liaisons that can assist community-based organizations with technical aspects of the benefit. Kitty Bailey, MSW, the CEO of the collaborative, said its experience navigating the implementation of other CalAIM benefits, such as Enhanced Care Management and Community Supports, positions it well to do this work for entities that deploy CHW/P/Rs.

“They hire the workforce, they do the services, and then they track all of that in our case management system so that we can do all the billing and claims on their behalf,” Bailey said. She explained that many of SDWC’s existing clients were eligible to bill for the new benefit when it came into effect but needed extra support to implement it.

“Setting up these programs inside of community-based organizations is very challenging, because the workflows that are required to make this work are not anything like any other program they’ve ever done before,” Bailey said. “This is a very different kind of project.”

The Need for Fair Reimbursement Rates

But even with technical assistance, many community leaders said Medi-Cal reimbursement rates are insufficient. At present, the rate is set at $26.66 for 30 minutes of direct contact with a patient.

“It’s not enough to build up the infrastructure we need,” said Wong.

Once a CHW/P/R accounts for additional labor other than the half-hourly billable rate — such as finalizing referrals, traveling to work sites, and completing administrative tasks — it becomes clear that the fees are inadequate, Fajardo said. More than one year into the benefit, he had only accepted two Medi-Cal referrals and intended to complete a thorough cost analysis before accepting more.

“We’re grateful for some level of reimbursement, but it’s okay to say that that’s not enough,” said Hedrick of CCUIH.

Moreover, billing is capped at two hours, which may limit patient interactions, said CPEHN’s Mackey, describing how she frequently spent as much as four hours with a single patient to understand the root cause of their diabetes. “It takes time to build trust,” she said.

“Doing 20 visits a day is not realistic, and it’s not aligned with the spirit of CHW/P/R services,” said Bailey, which has historically involved extensive outreach in the communities they have served — labor that goes unpaid within the current benefit model.

Ralph Silber, MPH, a consultant with expertise in the non-profit health sector, notes that beginning January 1, 2024, Medi-Cal is raising rates to 87.5% of Medicare rates for primary care and behavioral care services. Silber said that is a “huge step forward.” Since those decisions were made, Medicare set a new CHW reimbursement rate. So, although CHW/P/Rs were not included in the policy change, the Medi-Cal rate increases could set an important precedent. That’s because applying the same rate increase to the new CHW Medicare rate would almost double current CHW/P/R reimbursements from Medi-Cal.

“If it’s good enough for the doctors and therapists, it’s good enough for the CHWs,” said Silber.

For some organizations, another opportunity to fund unpaid hours could be the CalAIM Providing Access and Transforming Health Initiative (PATH), which offers one-time payments for administrative costs, said Rene Mollow, MSN, RN, deputy director of health care benefits and eligibility at DHCS.

Notably, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), which many underserved communities rely on, cannot bill for the CHW benefit because of their financial structures. “Many of our sites are FQHCs , and they’re not utilizing the state plan amendment mechanism for paying for community health workers,” said Anna Steiner, MSW, MPH, national program manager at Transitions Clinic Network.

A Collaborative Path Forward

State and industry leaders agree that bringing a wide range of community voices to the table is paramount for identifying opportunities for growth and improvement that will be felt on the ground.

“The state cannot enter the picture and co-opt the hard work that has happened at the grassroots level. Instead, the state must put the CHW/P/R voices at the forefront in guiding us on how to move this initiative forward,” Delgado and Torres said in their statement.

For Health Net’s Mittal, that collaboration is fundamental. “The most important thing that we do is be good partners, show up, try to understand, and support the organizations that have been doing this work successfully for a very long time,” she said.

Ultimately, these discussions indicate that everyone involved, from state officials to community leaders, wants to ensure that California’s underserved communities get the care they need — and that the diversity and grassroots nature of CHW/P/Rs is preserved.

“CHWs, doulas, peer support specialists – these are all examples of Medi-Cal saying, ‘We recognize the important role that these non-licensed community members can play in improving health outcomes,’” said Silber.

But creating sweeping change does not happen overnight, stakeholders and state officials acknowledge. “We expect within a couple years, we’re going to see more uptake, but it’s an ongoing process,” said Mollow. “Everything we do, especially when it’s new, takes time — and this is truly a paradigm shift.”

“We’re learning as we go,” said Fajardo. “There is hope. This is just the start.”

José Luis Villegas is a freelance photojournalist based in Sacramento, California, where he does editorial and commercial work. He has coauthored three books on Latino/x baseball. His work appears in the Ken Burns documentary The 10th Inning and in the ¡Pleibol! exhibition that debuted at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History and has been appearing at museums around the country. Read More