This story is a collaboration between the Guardian and the Trace, a non-profit newsroom covering guns in America. A more detailed version of the story can be found here.

Once upon a time in America, people rolled their eyes at seatbelts, four out of 10 high school students smoked cigarettes, and campers left their fires smoldering through the night. Then we changed. Not primarily because of policy reforms, but because teams of marketers crafted public health messaging campaigns in which chatty crash test dummies told us to buckle up, teens piled 1,200 body bags in front of the Philip Morris headquarters, and Smokey the Bear identified who can prevent forest fires.

Recently, big players in gun violence prevention have begun asking whether this tradition of transforming the US through advertising might be used to reform our relationship to guns.

Since its inception, the gun violence prevention movement has invested the bulk of its time and money in a top-down strategy: change gun policy in courtrooms and statehouses, the thinking goes, and the trajectory of gun violence in America will change too. But despite spending hundreds of millions of dollars on this approach and enjoying the support of most of the American public, the movement has failed to budge the metrics that matter most. Gun deaths have been climbing for decades, and in 2020, guns surpassed car accidents as the leading cause of death for young people. These losses have persuaded some gun reform advocates that it’s time to try a different strategy: go directly to the people.

For the first time, this bottom-up approach has been drawing major attention and funding in the gun violence prevention world. The Ad Council – kingmaker in the realm of public service announcements – is in various stages of campaign development with three separate gun violence prevention groups. Meanwhile, the Biden administration has been building out its own gun-safety messaging efforts focused on service members and veterans and, just last month, on red-flag laws.

But one of the most ambitious efforts to change Americans’ relationship to guns is being led by a non-profit founded two years ago, called Project Unloaded. Rather than trying to improve how existing gun owners handle their weapons, or curry public support for a specific policy, Project Unloaded is using marketing to attack the problem at the heart of gun violence: too many households own guns, and more access to guns leads to more deaths and injuries.

Project Unloaded has flooded the social media feeds of young people in a dozen cities with ads and influencer content about the threat that owning a gun poses, reaching more than 2 million teens an average of 30 times. And last summer, the group experimented with deeper in-person engagement on Chicago’s South Side, where gun violence is not an abstract problem. For six weeks last summer, 50 students from Chicago Public Schools were paid to design and implement a bespoke public-messaging campaign that several teenagers say fundamentally changed the way they saw guns – and made them question whether they want to own one.

A single statistic led to Project Unloaded’s founding: a Gallup poll found that the portion of Americans who believe that having a gun in the house makes it a safer place had jumped from 35% to 63% between 2000 and 2014.

The spike rattled Nina Vinik, the project’s founder and a civil rights attorney who has long been a player in the gun violence prevention world – not just because piles of public health research show the belief to be false, but because the falsehood has nonetheless been accepted by many people who are not part of the traditional gun-owning demographic. Women believe it. People of color believe it. Young people believe it.

It occurred to Vinik that while the gun industry had been aggressively pushing the message that guns are the solution to an unsafe world, there’s been no major push back with the empirical truth, uncovered in study after study: in an unsafe world, owning a gun makes you more vulnerable. Having a gun in the house makes suicide attempts more deadly, shooting accidents more common and domestic disputes more dangerous.

Project Unloaded’s wager is that if enough young people know the facts, and even a portion of them choose not to arm themselves, America’s gun death trends will, at long last, reverse course.

Focusing on young people makes sense. Half of gen Zers report that they think about mass shootings at least once a week, which isn’t surprising given that most were taught how to respond to an active school shooter before they were taught to read. Yet, even more than their elders do, young people have come to believe the myth that guns provide safety: sixty-eight percent of people under 34 believe a gun makes a house a safer place, compared to 61% of baby boomers.

When Vinik first learned of that contradiction, it struck her as an opportunity. Like older adults, young people have absorbed the falsehood. But it hasn’t yet been cemented into their worldview.

Project Unloaded launched its first campaign in 2022. It was dubbed SNUG, short for Safer Not Using Guns and, handily, the word “guns” backwards.

The campaign’s ads featured bright colors, lo-fi beats and simple, shorthand messages: “DYK… SUICIDES R 4X HIGHER 4 KIDS W/ GUNS @ 🏠… R U SNUG?” reads their top-performing 15-second ad. They placed ads on TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram in 12 cities, and have paid influencers to talk about the #yousnug campaign. One hair care influencer styled her curls while explaining that a gun can make domestic violence disputes more deadly. An actor and comedian in New York City, sipping her morning iced coffee, talked about finding herself in an active shooter situation on the subway. “That’s why I choose to be SNUG,” she concluded.

Meanwhile, Project Unloaded hired a dozen teenagers from around the US, whom they pay a stipend for providing feedback and TikToks. Vinik’s team runs all ad content by this youth council, Anvesha Guru, a 16-year-old high school senior from Wisconsin and the council’s social media chair, told me: “With the SNUG ads, they were like: ‘Are these colors too bright for young people? Will they find it cringy?’”

In addition to giving advice and making content, the council has taken on its own projects. This year, they launched a teen-focused SMS text program that sends out gun-safety stats, and are developing a toolkit for student clubs. They also published an independent research project showing that during the Hollywood labor strikes, depictions of gun violence shrank significantly without affecting ratings.

Most of the teens on Project Unloaded’s youth council grew up in places where shootings are most commonly self-inflicted. But could the messaging strategy work in a place like Chicago’s South Side, one of the rare places in the US where firearm homicides significantly outnumber firearm suicides?

Last July, Project Unloaded paid 50 Chicago Public School students to create a campaign against gun violence. The teenagers, who were connected with Project Unloaded after signing up for a youth summer jobs program, were split into teams and tasked with researching public health literature on gun ownership and violence. After that, they would work with professional mentors to develop a marketing campaign informing other young people of the facts.

But within days, some students were so restive that there was talk in the district of aborting the pilot and reassigning students to other jobs. Some students felt the assignment was dumb: they could do it, but why? It’s not like anyone listened to teenagers anyway. A couple of students reasoned that gun violence was a problem caused by adults, and it was wrong to ask kids to fix it on their summer break. One said she went to bed every night wondering if she’d wake up to a call that her brother had been shot. Googling studies on gun violence felt emotionally taxing.

District officials listened and tried to affirm their concerns. The group brainstormed how to make the project feel more authentic and useful to them and their peers. By the third hour of talking things through, the students said they were feeling better. The next day they got to work.

I told this story to Selwyn Rogers, founding director of the University of Chicago’s trauma and acute care center, the place most people on the South Side go for treatment if they are shot. Rogers, who also sits on Project Unloaded’s steering committee, wasn’t surprised. The young people he speaks with have divided feelings about guns. On one hand, they greatly fear them. On the other, having a gun gives them a sense of control over their life.

Still, Rogers said, there’s a role for Project Unloaded in places like the South Side. Gun violence, he said, is neither inevitable, nor unshakable. “You could never convince a 76-year-old guy that they should give up the gun they’ve had their entire life because they’re battling depression after their wife died,” he said. Young people are different: “Kids can change,” he said.

I asked everyone I spoke to for this story what they see as the closest historical analogue to these new cultural efforts on guns. Most pointed to the campaign against drunk driving, another effort of the Ad Council. In 1983, a time when “one more for the road” was still America’s general vibe, the first Drinking and Driving Can Kill A Friendship ad appeared on TV. A few years later, the ads adopted the term “designated driver”. Alcohol-fueled auto fatalities have dropped for a number of reasons; most analyses show that public health messaging has played a sizable role.

But none of the campaigns that have taken on America’s stickiest problems – drunk driving, teen smoking, seatbelts, littering – and found success are perfect parallels to gun campaigns, because guns occupy a unique place in American politics. There’s no pro-littering lobby, nor a constitutional amendment protecting Americans’ right to resist seatbelts. Crucially, these historical analogues got help from policymakers, who implemented smoking bans, drinking age increases and littering fines.

Still, Vinik says, there’s hope. Surveys indicate that at least 15% of teens repeatedly exposed to Project Unloaded’s messages shifted their view on whether owning a gun would make them safer, the group says.

Michael Anestis, the executive director of the New Jersey gun violence research center at Rutgers, has devoted much of his research in recent years to studying what makes an effective firearm suicide prevention messaging campaign. When I first spoke with him, he wasn’t familiar with Project Unloaded or the SNUG campaign, but liked the premise. One of the gun violence prevention movement’s “great failures”, he said, has been allowing the gun industry’s messages to “go into a vacuum”, with no pushback.

But he wondered whether a campaign like SNUG might work better if it offered an alternative, like how the drunk-driving campaign suggested designated drivers. What if, he posited, a campaign against gun violence did the same: don’t feel safe at home? Consider an alarm system. Or maybe adopt a dog. They both keep you safer than a gun would.

Even if messaging is fruitful, I asked Vinik: can America’s gun culture change without major policy wins prodding it along? The gun violence prevention movement has made policy inroads in some states, but has backslid in many others, and state borders are porous. The federal gun safety law passed in 2021 – the first of its kind in decades – is often criticized as toothless. The supreme court 2022 Bruen decision will make gun restrictions harder to pass and maintain, because it requires them to have historical precedents from the nation’s earliest era.

Vinik admitted that cultural campaigns have their limits. “There’s no messaging campaign that’s going to solve this problem on its own,” she said. Then she threw the question back: would the policy fights have been more successful if they’d happened alongside efforts to change our culture? She’s convinced the answer is yes.

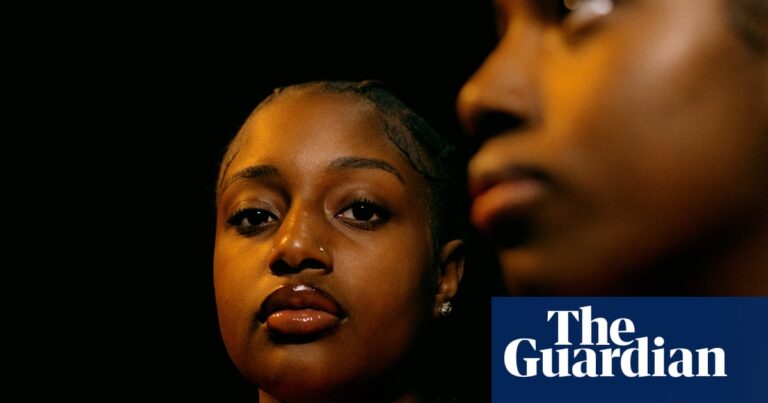

Each of the three groups in Project Unloaded’s summer jobs pilot program in Chicago gave themselves a name. Best friends Arinek Shorter and Egypt Paige, both 17, were on a team that dubbed itself Peace Love Justice, aka PLJ.

On the first day of their summer jobs pilot program, Olivia Brown, Project Unloaded’s program director, handed out a survey to see where the students stood on gun ownership. Twenty percent said they didn’t plan to be gun owners, and another 19% weren’t sure. The majority said they would either probably or definitely own a gun one day.

Both Arinek and Egypt found the data showing that guns don’t make you safer persuasive, but other members were less moved. “They felt that guns will protect them from all the dangers in Chicago,” said Egypt. “But we showed them the research and it’s like, no, this is not what’s keeping you safe, this is what’s putting you in harm’s way.”

The team found themselves debating the issue over and over. Arinek understood why many of her peers disagreed with her change of heart. They were the product of an environment that lacked resources, opportunity and safety. “In our community, all we know is guns. All we know is that it’s a dog-eat-dog world. And so they’re like: ‘If they have a gun, why can’t I have a gun?’” she said.

It was in the middle of one of these debates that the team came up with the marketing slogan they would eventually use for their marketing campaign: “A lot of people kept saying: ‘Guns, they help you, they give you power, they keep you safer,’ and it was just like a click – like: ‘Guns don’t give you power!”

The phrase quickly became a refrain. “Every time somebody said they need a gun to be safe, we would hit them with: ‘Guns don’t give you power’ – and let me give you the facts and statistics why they don’t,” said Arinek, who aspires one day to be an attorney.

On the last day of the program, the three teams presented their marketing proposals to an assembly of the 500 other teens in the district’s summer jobs programs. Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson was on hand to judge; the winning proposal would be incorporated into Project Unloaded’s next major campaign, which the organization was developing specifically to share in communities with high levels of community violence.

The first group’s campaign slogan was: “Enough is enough – change the lyrics!” They proposed asking hip-hop artists and producers to create a “gun edit” of their songs that left out language glorifying gun violence. The second campaign, “Watch where you aim”, encouraged teens to aim higher than a life of gun violence.

Arinek and Egypt’s team went last. Arinek introduced their theme, and Egypt, who aims to one day be a doctor, followed with a skit debunking gun myths. Next, their group performed a spoken-word poem they had collectively written on the theme “Guns don’t give you power”.

“When I see a gun, my mind automatically tells me to run,” Egypt began. “Run from the pain. Run from the shame. Run from the streets calling my name.” Arinek’s lines came later: “Fear of love. Fear of fun. Fear of letting my guard down. knowing that one gun can take my life. Fear that I might not even make it home tonight. Fear that my dreams are no longer in sight.”

When the votes were in, Peace Love Justice had won. The team erupted in cheers.

Before the students left, Vinik and Brown tried to wrangle them into taking another survey, but many of them had already headed for the doors. Of the 18 who took it, 20% had moved from “probably” or “definitely will own a gun” to “undecided/unsure”. Vinik counted that as a win.

Among the students who did not fill out the survey that day was a young man on a team called the Strikers. He had been unable to help deliver their “Watch where you aim” presentation, because he was recuperating. Not long before, he had been shot in the leg.