BETHEL, N.Y. (AP) — Woodstock didn't even happen at Woodstock.

Considered one of the seminal cultural events of the 1960s, this legendary music festival was held 60 miles away in Bethel, New York, an even smaller village than Woodstock. This is a fitting misnomer for an event that is both real and legendary. And rather than a relationship with a place, the memories this event evokes are about the state of mind of society as a turbulent decade comes to an end.

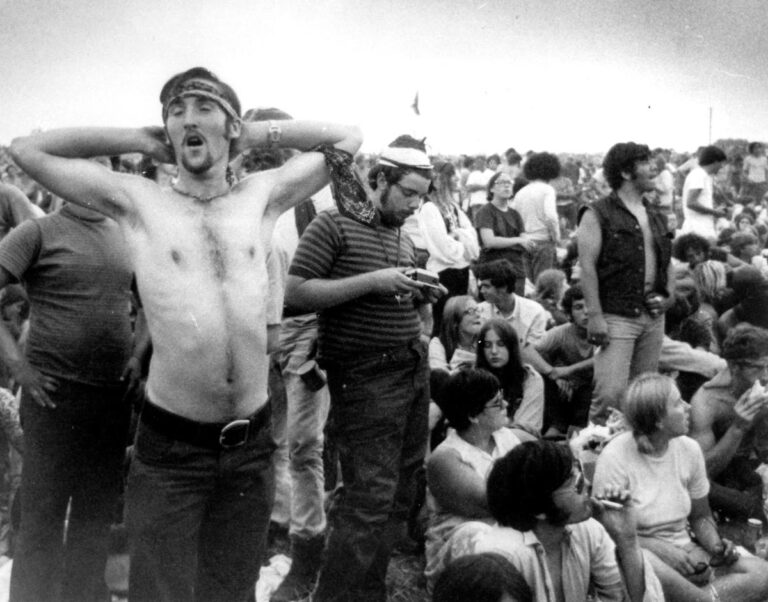

From August 15th to 17th, 1969, an estimated 450,000 people flocked to an area owned by dairy farmer Max Yasgur to take part in the Aquarian Exposition, which promised “three days of peace, love, and music.” Ta. Most of them were teenagers or young adults. People are now in the twilight of their lives, at a time when only a small portion of the population is living through the memories of the 1960s.

Thanks to this ticking clock, the Bethel Woods Museum, located at the festival site, is undertaking a five-year project to sift fact from legend and collect first-hand memories of Woodstock before they fade away. It's a quest that took museum curators on a cross-country pilgrimage to record and preserve the memories of those who were there.

“We need to see history from the perspective of people who have had first-hand experience,” says music journalist Rona Elliott, 77, who works as one of the museum's “community connectors.” Her Elliott has her own story about the festival, and she worked with organizers like Michael Lang, who was there and entrusted his archives to her before his death in 2022. was doing.

According to Elliott, Woodstock is “like a jigsaw puzzle, a compilation of everything that happened in the '60s.”

Exploring oral history

Woodstock attendees have conducted hundreds of interviews over the decades, especially on major festival anniversaries. But the Bethel Woods Museum is relying on techniques similar to those of the late historian Studs Terkel, who produced hundreds of oral histories about what it was like to survive the Great Depression and World War II. The project started in 2020 is deepening further. .

“Being interviewed for a paper or documentary is different than having oral history cataloged and preserved in a museum,” says Neil Hitch, senior curator and director of Bethel Woods Museum. “We had to go where the people were. You can't just call someone on the phone and talk about personal, private memories from festivals where they might have been 18 or he was 19. They don't really know what to say when asked to do something.”

To find and meet the people who can tell the story of Woodstock, the museum received grants totaling more than $235,000 from the Association of Museum and Library Services. That's enough money for curators and community collaborators like Elliott to travel across the country and document the story.

This journey began in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The farm is home to a pig farm that helped feed hippie volunteers like Hugh “Wavy Gravy” Romney and Lisa Roe to the Woodstock crowd. Museum curators traveled to Florida, boarded the cruise ship Flower Power, and visited Columbus, Ohio, near the former home of festival performers Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful earlier this year. Made a trip to California that included visiting a community center in San Francisco. Died.

Richard Schellhorn, now 77, traveled from his home in Sebastopol, Calif., to San Francisco to talk about his Woodstock experience. He was originally hired as a security guard at the box office when the festival was scheduled to be held in Wallkill, New York, but community backlash delayed the change to the Bethel venue.

Schellhorn was still reporting to work at Bethel, but it soon became clear that his services were not needed as the festival became so crowded that organizers stopped selling tickets.

“I was walking around in Woodstock and Hugh Romney came up to me and said, 'Are you working?'” Schellhorn recalled to The Associated Press before sitting down to record an oral history. Ta. I was fired! He said, “So, would you like to volunteer? “said. ”

Kjöllhorn ended up working in a tent set up to help people who had had bad experiences with the hallucinogens they had ingested. He was enjoying his first ever concert when he was stoned.

“It felt like we were all in the same weird boat,” Schellhorn said. “There were no neighborhoods where people were wealthy. No one was special to begin with.”

Before attending Woodstock, Schellhorn said he was lonely, intending to pursue a career in marketing. After Woodstock, he became so extroverted that he lived for several years in a commune in Colorado, where he then spent 35 years as a dialysis technician.

Memories experienced up close

Another Woodstock attendee, Akinyele Sadiku, also came to meet the San Francisco curator to dredge up memories of watching the festival from 25 feet (7.6 meters) from the stage.

The festival wasn't scheduled to start until Friday, but Sadiq left on Wednesday by bus to Bethel. When his bus broke down, he hitchhiked to the festival site by noon on Thursday and was able to secure a spot so close to the stage that he can be seen in photos taken during the performance. Ta.

By the time Sadiq left Bethel a few days later in a hearse that his fellow festival-goers had converted into a van, he had changed.

“I didn't have any real direction until I went to Woodstock. I basically didn't have many friends, but I knew I wanted peace and justice,” she says. “I wanted to be around creative people who were trying to make the world a better place,” Sadiq, now 72, told The Associated Press before getting married. His oral history was recorded. “Before Woodstock, I thought if I lived in a small town, there would be a dozen or so people I could get along with. But then I realized there were at least half a million people. It's just me. It gave me hope.”

Hitch said curators have heard many life-changing experiences in collecting more than 500 oral histories so far, and are confident they will collect even more in the coming year. . Community Connector visited Florida last month and is headed to Boston in March and New York City in early April. This will be followed by a round-trip trip to New Mexico and Southern California.

The museum will focus on locating and interviewing festival attendees across New York state, where Hitch estimates about half of the Woodstock crowd still lives.

The museum will spend 2025 thoroughly researching the oral history and then working on special projects, such as reuniting friends who attended the festival together but now live in other parts of the country.

Elliott believes that “karmically and cosmically” the oral history project was what he was meant to do.

“We want this to be an educational tool,” she says. “We don't want historians to tell us about a spiritual event that just looked like a musical event.”