The main motivation for farmers to store and sell grain after harvest is better prices. However, it is not clear whether post-harvest delivery will result in higher prices than delivery at harvest or “off the combine.” About 60% of the corn and soybeans produced in Illinois were still sold at the end of the year, but these totals hide wide variation among farmers. On many farms, virtually all of his year's production is in stock at the end of the calendar year.

The extent to which unsold produce poses a price risk management problem for a farm depends on how large and volatile postharvest marketing profits are. That is, the price the farm receives for its post-harvest sale minus the price the farm could have received. By selling at the time of harvest. Although we expect that marketing margins will be positive due to typical seasonal price increases, there can be no assurance that this will be the case. Additionally, farms have access to a wide range of sales agreements to conduct both pre-harvest and post-harvest sales, making it difficult to determine the “right” comparison between pre-harvest and post-harvest.

This article examines the postharvest marketing performance of Illinois Farm Management Association farms. I consider the allocation of marketing profits by comparing the price a farm receives after harvest to the price the same farm receives at a near-harvest sale in the same marketing year. This eliminates the confounding effects of location, marketing skills, and other farm-specific factors that influence marketing performance.

We find that farms realize gross revenues from post-harvest marketing that, on average, closely match typical seasonal cash price increases. Farmers who realize a sale after January 1 receive a price that is on average consistent with the typical price increases that follow the near-harvest period. However, the range of outcomes achieved is large, and negative returns often occur. On a risk-adjusted basis, the benefits from postharvest marketing appear small.

Seasonality of corn and soybean prices

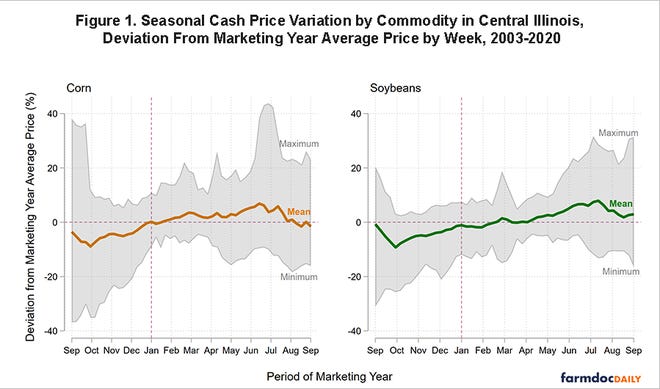

When prices rise late in the marketing year, a typical seasonal price pattern, farm managers and other decision makers in the grain supply chain have an incentive to store grain and sell it for post-harvest delivery. It can be obtained. Figure 1 illustrates seasonal patterns for corn and soybeans using USDA Agricultural Marketing Service cash market price data for central Illinois from the 2004-2005 through 2019-20 market years. Note that the corn and soybean sales year runs from September 1 to August 31 of the following year.

The values shown in Figure 1 are the deviations in a given week from the simple market year average price, which is the unweighted average of daily price observations for that market year. These deviations remove differences in price levels across marketing years to focus on seasonal price changes in each year.

Use the average price series to represent typical seasonal price patterns and baseline marketing profits. The average price series is the average difference between the price for a particular week and the average price for the marketing year. The average price series shows that corn and soybean prices both reached their seasonal lows in early October. The average weekly deviation from the seasonal average price (bold line in Figure 1) is lowest at this point, coinciding with a typical harvest season in central Illinois. Seasonal peaks occur in June and July. Prices tend to rise steadily from October to June.

The average price patterns in Figure 1 show that both corn and soybean prices have increased by about 20% between seasonal lows and highs. Comparing the near-harvest period from September to December and the period after January 1 (separated by the vertical line in Figure 1), typical price increases are around 6-7%. However, the extreme values shown in Figure 1 indicate that there can be large differences between observed prices and typical seasonal patterns in any given year.

Farmers and other grain marketers have other strategies to realize post-harvest marketing benefits. The futures and futures contract markets often experience “carry,” where the price of deferred delivery exceeds nearby prices. By selling ahead, or selling carry, for later delivery, farmers can realize marketing benefits and reduce price risk. The ability to transfer contracts greatly increases the marketing options available to farmers and greatly expands the potential for marketing results.

Defining a benchmark return for post-harvest grain marketing is difficult when forward contracts exist, such as the typical cash price increase shown in Figure 1. For example, if a farmer is in agricultural production, the cash price at harvest may no longer be an appropriate reference price. Harvest sales are realized on pre-harvest grain sales. Some evidence suggests that pre-harvest sales may realize a weather risk premium compared to prevailing prices at harvest.

actual marketing profit

To evaluate marketing performance and assess the extent of marketing benefits, I consider realized selling prices in both the near-harvest and post-harvest periods. Rather than measuring marketing performance against an assumed marketing strategy, such as comparing actual sales prices with observed prices for cash sales at harvest, we measure marketing performance against realized prices for post-harvest sales and for sales close to harvest. Consider realized marketing performance by comparing realized prices. To harvest. Because this comparison is farm-specific, we control for the possible influence of location, marketing skills, and other farm-specific factors that influence marketing performance but do not change over time.

I collected data on annual corn and soybean stocks and production for approximately 16,000 farm observations from FBFM from 2003 to 2020. Merely observing sales volume and sales value for a calendar year is insufficient to evaluate postharvest marketing performance. Includes sales of both old crop inventory and new crop production. However, the Illinois FBFM also records the quantity and value of so-called old crop and new crop sales. New production sales are the sales of the current calendar year's production realized before the end of the calendar year. I call this a near-harvest sale. Close-to-harvest sales are realized in the sense that deliveries are made before January 1st and profits are earned. Unsold merchandise stored in on-farm warehouses, merchandise shipped to commercial warehouses where title is retained, and merchandise stored anywhere other than prior to shipment. Items for which delivery and transfer of ownership are contracted after January 1st will be considered vintage sales for the next calendar year. I call these old crop sales deferred sales.

I measure the total postharvest marketing benefit as a percentage of the difference between deferred and near-harvest sales. This is the total profit excluding costs associated with post-harvest marketing, such as the physical and opportunity costs of holding inventory and interest costs. Accounting for percentage differences allows comparisons between marketing years at different price levels.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of total revenue across marketing years from 2003/04 to 2019/20. This diagram shows that both positive and negative returns are possible. The total profit realized ranges from approximately -40% to +50%. The most common outcome is near-zero returns. The small colored bar along the horizontal axis shows the average return for all years. Average gross margins are approximately 7% for corn and 6% for soybeans. These values are very similar to the seasonal average cash price increases before his January 1 and after his January of the marketing year, shown in Figure 1.

Although the distribution of marketing outcomes in Figure 2 is informative about the potential benefits to postharvest grain marketing, there are several caveats. First, distribution pools results across a wide range of years and market conditions. In some years, most farms realize significant positive returns. In other years, the opposite is true. Perhaps a better measure of potential variation in results would be year-specific variation across farms.Upcoming articles on post-harvest grain marketing

Second, this distribution does not represent all farms. Revenue can only be calculated for farms that have both near-harvest sales and post-harvest deferred sales, thus excluding farms that do not have near-harvest sales. This condition is common. The distribution does not include approximately 40% of farms. Assessing marketing performance is more difficult and will likely have to rely on comparisons to assumed benchmark prices.

what it means

The postharvest marketing performance described in this article provides at least three useful insights into farm-level grain marketing.

- The average total return is positive. We should expect farms that maximize future expected profits to hold inventory and market grain after harvest.

- Gross profits come with significant risks. Assuming that inter-farm variation is an indicator of the risk of future post-harvest marketing activities, risk-adjusted returns appear small. Farms engage in postharvest sales not only when they receive positive returns from postharvest sales (i.e., carry sales) through futures contracts.

- Actual prices received from pre-harvest sales for delivery near harvest may be better than common price benchmarks used to value post-harvest sales, such as cash prices at harvest. there is. One of the causes of negative returns in this case is the success of marketing efforts during the pre-harvest period.

This analysis suggests that farmers need to carefully consider the risks of post-harvest grain sales, especially unhedged sales. Although farmers are realizing overall benefits from selling later, the mixed outcomes of postponing sales indicate significant downside risk from the loss of stored grain. Farmers can manage this risk and secure profits from deferred sales through forward contracts. Seasonal price increases are real, but they cannot be guaranteed unless farmers use futures contracts to secure their profits.