patient population

The design of this study was modeled after the initial pilot intervention described above.7. We prospectively enrolled 70 adult patients diagnosed with NAFLD from a liver outpatient clinic in Ann Arbor, Michigan from April 2019 to March 2020 with follow-up through August 2020. went. To meet diagnostic criteria for NAFLD, participants were required to undergo imaging tests. [ultrasound (US), Vibration controlled transient elastography (VCTE) (Fibroscan, Echosens), computed tomography (CT), or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)] Liver biopsy showing steatosis within the past 24 months, or liver biopsy pointing to hepatic steatosis within the past 36 months, and no or minimal (<5) weight loss since these tests. %). This testing period was chosen to minimize the need to repeat previously performed tests to qualify for participation in the study. Ten subjects had completed imaging or biopsies more than 6 months before enrollment, and the remainder had their tests completed within 6 months of enrollment. Patients with other causes of chronic liver disease, such as hepatitis B or hepatitis C, were excluded. Alcohol assessment was conducted based on medical record review and participants' responses to questions during the screening visit. Patients were excluded if they reported 14 or more drinks per week for men or 7 or more drinks per week for women at the screening visit or had a history of alcohol use disorder. All participants were required to be able to participate in a walking program and a basic nutritional intervention (can follow a Mediterranean or low-carbohydrate diet). Those with severe comorbidities (severe cardiopulmonary disease, severe musculoskeletal disease, poorly controlled diabetes, active malignancy), liver decompensation, history of liver transplantation, or hepatocellular carcinoma were excluded. Participants with decompensated cirrhosis demonstrated the systemic benefits of a healthier lifestyle, in addition to data supporting the role of lifestyle interventions in this population in reducing the risk of clinical decompensation, including reducing the degree of portal hypertension. Eligible for registration due to its health benefits.8. Those taking medications that can cause fatty liver or weight loss, those planning obesity treatment, or participating in other structured lifestyle programs were also excluded. Participants need a computer or smartphone with an internet connection.

Data collection

At enrollment, we obtained data on demographics, medical comorbidities, vital signs and anthropometry, laboratory tests (up to 6 months from enrollment), measures of physical function and frailty, liver imaging and several survey measures. . Physical function was assessed using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). The 6MWT is an efficient and low-cost method to assess functional exercise capacity that has been validated in patients with chronic liver disease.9. Frailty was assessed using dynamometric grip strength according to established protocols by trained research staff. Three measurements were taken of him on each hand and handedness was recorded. VCTE liver stiffness (LSM) and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) measurements are available if the results of a VCTE performed within 6 months prior to enrollment are available and if the participant has lost 5% or more of weight since the test. Taken at baseline unless otherwise indicated.

Physical activity was assessed using a validated short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).Ten. Dietary assessments were conducted using the widely used “Conversation Starter” survey as a brief measure of healthy eating.11. This is an eight-question questionnaire that assesses the frequency of consumption of fast foods, vegetables, fruits, sugar-sweetened beverages, low-fat and lean proteins, potato chips and crackers, desserts/other sweets, and margarine/butter/meat fat. It's a tool. Each answer is scored from 0 to 2 with a maximum of 16 points, with higher scores indicating unhealthy eating habits. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measurements were obtained using the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-NAFLD (CLDQ-NAFLD).12. This tool consists of 36 items across six domains: fatigue, abdominal symptoms, emotional functioning, systemic symptoms, activity, and worry. Each question requires an answer on a 1-7 Likert scale ranging from “always” to “never.” Responses to these items were averaged to give a summary score from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating higher his HRQOL.Motivation to change health behaviors was assessed using a validated Stages of Change Questionnaire13. This model categorizes readiness to change health behaviors into one of his five categories: (1) Before contemplation. (2) Contemplation. (3) Preparation. (4) Action. (5) Maintenance.

At 6 months, anthropometry, laboratory studies, and questionnaires were repeated. Follow-up measures were limited due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited in-person study visits and data collection. Participants received a $25 gift card each time they completed a study visit. Study procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to the study. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was first registered on his Clinicaltrials.gov on February 12, 2019 (NCT03839082). The results of the study will be reported according to CONSORT 2010 guidelines.

lifestyle intervention

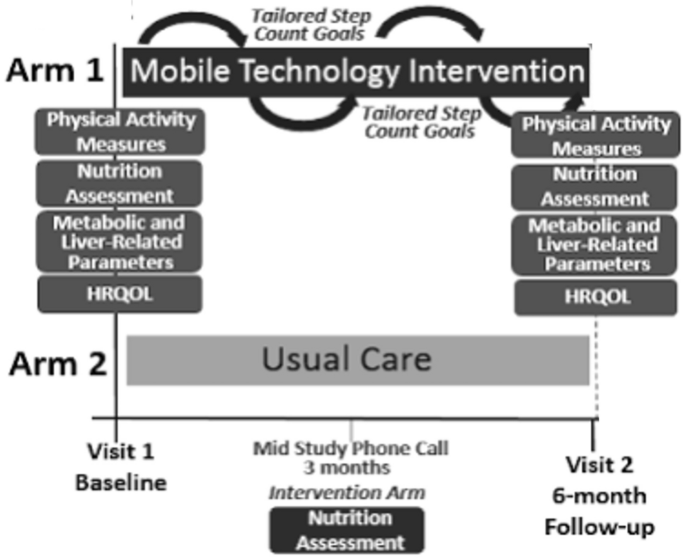

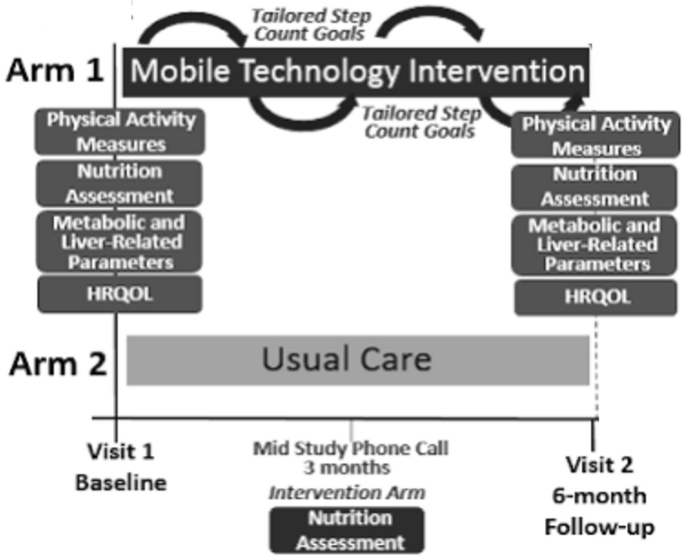

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either usual care at a general liver disease clinic or a mobile technology-based intervention for 6 months (Figure 1). At our center, the usual care for her NAFLD patients without decompensated cirrhosis consists of visits every 6–12 months. The visit lasts approximately 15-20 minutes and includes a weight check, recent lab tests, and her VCTE/imaging tests as ordered. Management usually consists of a brief overview of lifestyle changes, including improving nutrition and physical activity. Patients receiving usual care did not consistently receive specific educational materials or assessment by a dietitian. Vitamin E is prescribed to a small number of patients. A similarly small number of patients are formally referred and then evaluated by a dietitian.

Mobile technology-based interventions compared to usual care.

Mobile technology-based lifestyle intervention design is derived from a previous pilot study7. Participants in the intervention group received their Fitbit Zip to track step counts at enrollment. Fitbit wirelessly syncs data from your tracker to the Fitbit software or app. Research staff helped download the software and instructed participants to wear their FitBits during waking hours each day. If a participant has questions or problems regarding the use of her FitBit, she can contact research staff at any time.

Research staff captures users' step count data weekly for analysis and provides step count information based on customized goals (10% increase per week, from ~800 steps per week to ~10,000 steps/day) and motivational messages. Provide personalized feedback to subjects. Email your previous step counts and nutrition assessment. These goals were modeled after the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) physical activity recommendations.14. Patients who have consecutive days with no data recorded or who have other signs of low FitBit usage (days with minimal step count) will be contacted by study staff by email or phone as appropriate. and encouraged its use. Feedback was given weekly for his first 3 months and biweekly for his subsequent 3 months. Patients in the intervention group also underwent a nutritional assessment by a dietitian specializing in NAFLD at enrollment. As part of longitudinal feedback emails, patients were also asked about their dietary/nutritional progress. Participants in the intervention group also received her NAFLD education folder containing: (1) Her NAFLD disease information including diagnosis, clinical symptoms, natural history, and treatments. (2) NAFLD nutritional recommendations (including menu examples); (3) NAFLD physical activity recommendations (e.g., walking programs and physical activity records); (4) Weight tracking log. (5) Resources for diet and exercise programs15. Participants were encouraged to incorporate physical activity other than walking. Data on the type of physical activity participants regularly engaged in were obtained with the IPAQ assessment.

interesting results

Results included correlations between lifestyle behaviors and HRQOL, improvements in metabolic and liver-related clinical parameters, HRQOL, and physical activity patterns 6 months after implementing the mobile technology intervention. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has limited in-person medical and research visits, follow-up data were limited to survey data, limiting pre/post analysis of intervention impact.

statistical analysis

We performed descriptive and bivariate analyzes to assess the impact of the intervention on baseline characteristics and outcomes of interest. For descriptive statistics, the median and interquartile range (IQR) are shown for continuous data, and frequencies and percentages for categorical data. Correlations between lifestyle patterns and variables of interest were determined by univariate and multivariate linear and logistic regression. Candidate variables for multivariate analysis were selected based on the results of univariate analysis, biological plausibility, and results of previously published studies. End-of-intervention analysis assessed median differences using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, given the small sample size and wide distribution of data points within the cohort. P Values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant. All analyzes were performed in STATA 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).