In addressing the study’s first objective, we sought to discern differences in clinical factors, dietary intake, and lifestyle habits between Malaysian Malay women with and without GDM at the T0 and T1 trimesters. The investigation revealed distinct patterns between the two groups at both time points. Participants with GDM exhibited elevated FBG levels, 2-HPP levels, and increased body weight. Furthermore, they were more likely to fall into the overweight and obese BMI categories. Notable variations in lifestyle habits, including sleep quality, darkness during sleep, and physical activity levels, were observed. Dietary intake also differed, with variations in iron, meat, fats/oils, carbohydrates, and fruit consumption.

In comparison, the current study aligns with systematic reviews21,22 that have consistently reported higher FBG and postprandial levels in GDM groups, indicating poorer glucose tolerance. Notable changes in weight and BMI categories were observed among Malaysian Malay women with and without GDM in the T1, compared to the earlier T0 stage. The higher weight and increased likelihood of being overweight or obese in the GDM group align with previous studies that have reported an association between GDM and higher BMI23,24,25. Changes in weight and BMI during pregnancy, particularly in the context of GDM, require careful consideration. It is expected that women will experience weight gain during pregnancy due to factors such as fetal growth, increased blood volume, and expansion of maternal tissues26. Monitoring weight gain and ensuring it aligns with recommended guidelines based on pre-pregnancy BMI is crucial.

Women with GDM had higher total fat intake than those without GDM at T0. This higher fat intake could contribute to increased insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism, factors associated with GDM development27,28. Additionally, the higher iron intake observed in the GDM group aligns with systematic reviews reporting higher iron requirements during pregnancy, particularly in women with GDM29. Iron is crucial for maintaining hemoglobin levels and preventing iron deficiency anemia, which can negatively affect maternal and fetal health30,31,32. However, it is essential to note that pregnant women, especially those with other known GDM risk factors, should avoid excessive heme iron-enriched food29. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between iron-enriched foods and GDM within the Malaysian Malay population.

Moving to the T1 trimester, the GDM group showed increased meat and fats/oils consumption compared to the non-GDM group. It aligns with studies suggesting a potential association between GDM and a higher intake of animal-based foods and unhealthy fats33,34. While lean meat sources can provide essential nutrients, excessive red or processed meat intake may increase saturated fat and cholesterol levels, potentially exacerbating insulin resistance28,35. Moreover, the higher intake of fat/oils in the GDM group could contribute to excessive calorie intake and impact glycemic control36. Carbohydrate intake, another crucial aspect in GDM management, exhibited variations between the two groups. The GDM group had higher carbohydrate intake at T0, highlighting the importance of monitoring carbohydrate consumption to prevent rapid blood glucose spikes and challenges in glycemic control37,38. At T1, both groups showed a decrease in carbohydrate intake, reflecting dietary modifications aimed at managing GDM through carbohydrate monitoring and control. Fruit consumption, often recommended for its valuable nutrient content and fiber, was lower in the GDM group at T0 and T1. Furthermore, lower fruit consumption may be associated with limited nutrient diversity and inadequate fiber intake39,40, potentially impacting GDM management. This finding raises concerns as fruits provide essential vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber that support overall health and glycemic control.

The lower satisfaction with sleep quality reported by the GDM group aligns with previous research suggesting a relationship between poor sleep quality and an increased risk of GDM41. Disrupted sleep patterns and inadequate sleep duration have been linked to insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism, critical factors in GDM pathogenesis42,43. Interventions aimed at improving sleep quality and promoting healthy sleep habits may have implications for preventing and managing GDM. The difference in darkness during sleep is an intriguing finding. The higher proportion of participants in the GDM group reporting complete darkness during sleep may indicate an association between melatonin secretion and GDM. Melatonin, a hormone released during the night, has been shown to play a role in glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity44,45. Further research is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms and potential interventions related to light exposure during sleep in the context of GDM.

Physical activity levels also differed between the two groups, with the GDM group having a lower proportion of individuals with high physical activity levels. This finding is consistent with a systematic review suggesting an inverse relationship between higher physical activity and GDM risk46. Regular physical activity has improved insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and cardiovascular health47,48. Encouraging pregnant women, including those with GDM, to engage in appropriate physical activities under healthcare guidance can improve glycemic control and overall health outcomes.

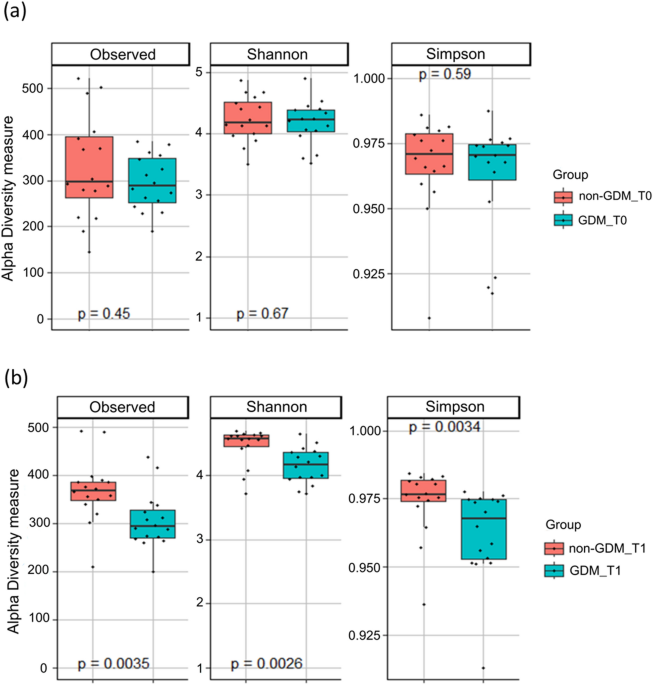

The study revealed noteworthy insights in addressing the second objective centered on discerning differences in gut microbial profiles between Malaysian Malay women with and without GDM at the T0 and T1 trimesters. The analysis of gut microbial profiles revealed significant disparities in the abundance of specific microbial groups at different taxonomic levels between the non-GDM and GDM groups. Surprisingly, at T0, no substantial differences in microbial diversity emerged between the two groups. However, by T1, the GDM group demonstrated a marked reduction in alpha diversity compared to the non-GDM group. These outcomes substantiate the initial hypotheses, implying that GDM may influence the composition of the gut microbiome. The unexpected absence of diversity differences at T0 and the subsequent decline in alpha diversity at T1 underscore the dynamic nature of the gut microbiome during pregnancy, with the impact of GDM becoming more apparent in later stages.

Furthermore, the present findings are consistent with previous research suggesting significant differences in the gut microbial diversity and composition between women with and without GDM during different stages of pregnancy. For instance, Koren et al. conducted a study on 91 pregnant women with varying pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational diabetes status and their infants to understand their role in pregnancy better49. They found that the gut microbiota underwent significant changes from the first to the third trimester of pregnancy. These changes included a remarkable expansion of microbial diversity among mothers, an overall increase in the abundance of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, and a reduction in overall microbial richness. These findings highlight the dynamic nature of the gut microbiota during pregnancy and suggest that the third trimester is a critical period of microbial community remodeling. Similarly, Crusell et al. examined the gut microbiota of pregnant women with (n = 50) and without GDM (n = 157) and found significant differences in microbial diversity and abundance3 and observed distinct microbial profiles associated with GDM. The diagnosis of GDM during the third trimester of pregnancy is associated with an altered composition of the gut microbiota compared to pregnant women with normal blood sugar levels3. The present study and previous investigations3,49,50 provide compelling evidence for the influence of GDM on gut microbiome composition. It suggests that GDM, as a metabolic disorder, can impact the diversity and abundance of microbial taxa in the gut as pregnancy progresses. It supports the concept that metabolic dysregulation associated with GDM may extend beyond glucose metabolism and affect other physiological processes, including the gut microbiota.

Furthermore, in the present study, the taxonomic analysis at the genus level revealed a difference in the abundance of Victivallis between the non-GDM and GDM groups. It is significantly reduced in the GDM group than non-GDM at T1. This finding suggests a potential association between the reduced abundance of Victivallis and the development of GDM. However, there is a lack of existing literature specifically exploring the abundance and activities of Victivallis in disease development. Victivallis is a recently described genus, and its role in the gut microbiome, diseases, and complete characterization is yet to be fully understood51,52. Further investigations are necessary for the species Victivallis due to its recent discovery and limited understanding of its role in the gut microbiome and its potential implications for diseases such as GDM. Understanding the functional significance of Victivallis in GDM pathophysiology is crucial to gain insights into its potential involvement in metabolic regulation, inflammation, and other relevant processes. Identifying reduced Victivallis abundance in Malaysian Malay pregnant women with GDM compared to non-GDM during the third trimester highlights the need for further research to validate and expand upon these findings.

The analysis provided valuable insights in exploring the final objective to reveal associations between clinical factors, dietary intake, lifestyle habits, and gut microbial profiles during pregnancy (T0 and T1) in Malaysian Malay women with and without GDM. Positive correlations were observed between Bacteroides and omega-3 PUFAs in Malaysian Malay pregnant women without GDM at T1. Negative correlations were observed between Roseburia and omega-3 PUFAs. It suggests a potential link between dietary intake of omega-3 PUFAs and gut microbiota composition during the later stages of pregnancy. Omega-3 PUFAs are known for their anti-inflammatory properties and have been associated with various health benefits. Previous studies have also reported associations between dietary factors, particularly omega-3 PUFAs, and gut microbiota composition53,54,55,56,57. However, further research is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms and their implications for maternal and fetal health.

The study also identified positive correlations between specific microbial taxa (Lactiplantibacillus, Parvibacter, Prevotellaceae UCG001, Vagococcus, and Victivallis) and physical activity levels in Malaysian Malay pregnant women with GDM at T0. Physical activity has been recognized as a modulator of the gut microbiome, influencing microbial diversity and composition. The findings suggest that physical activity level during the T0 may be associated with specific microbial taxa in GDM individuals, highlighting the potential impact of exercise on the gut microbiome in the context of GDM58,59,60.

Furthermore, correlations were observed between microbial taxa and gravida and parity. Gravida refers to the number of pregnancies a woman has had, while parity refers to the number of births. Previous research has shown that parity influences the gut microbiota of offspring61, indicating its impact beyond the mother. These associations suggest that the reproductive history of GDM individuals, as indicated by gravida and parity, may contribute to variations in the gut microbial composition during the T0 among Malaysian Malay women.

Indeed, the observed microbial variations in Malaysian Malay women with and without GDM raise exciting questions about the potential role of gut microbiota in developing and progressing GDM. While the exact mechanisms are still being investigated, several hypotheses can be proposed based on the current findings.

Firstly, the gut microbiota has been implicated in regulating glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity62,63. Disruptions in the composition and diversity of gut microbiota in Malaysian Malay pregnant women with GDM may lead to impaired glucose metabolism and insulin resistance, both critical factors in the development of GDM.

Secondly, imbalances in gut microbiota can trigger an inflammatory response and affect immune regulation64,65. Chronic low-grade inflammation contributes to insulin resistance and the pathogenesis of GDM. Changes in the gut microbial composition in Malaysian Malay pregnant women with GDM may influence the production of inflammatory markers and modulate the immune response, thereby influencing the risk of GDM.

Thirdly, the current study’s findings suggest that specific bacterial markers associated with butyrate production exist in non-GDM individuals but not those with GDM. These markers include taxa such as Ruminococcaceae, Roseburia species, Oscillibacter species, Lachnospiraceae UCG010, Flavonifractor, Butyriciproducens, [Clostridium] innocuum group, and Bacteroides_caccae. Butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), is produced by certain bacteria in the gut through the fermentation of dietary fibers66,67. It has been recognized as an essential energy source for colonocytes and has shown the ability to regulate glucose and lipid metabolism68. The correlation between butyrate-producing bacteria and metabolic homeostasis suggests that these bacteria may be crucial in maintaining metabolic health. The current findings imply that a lack of abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, as observed in GDM individuals, may have implications for glucose and lipid metabolism regulation. Consequently, alterations in the gut microbiota, precisely the absence or reduced abundance of specific butyrate-producing bacteria in the GDM group, may contribute to the development or progression of GDM.

Lastly, dysbiosis in the gut microbiota can increase gut permeability, allowing the translocation of bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into the bloodstream69,70. This phenomenon, called endotoxemia, may trigger an inflammatory response and contribute to insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction in Malaysian Malay pregnant women with GDM.

It is important to note that the observed microbial variations may not solely be a cause but rather a consequence or marker of GDM. Further research is needed to establish causality and elucidate the complex interplay between gut microbiota, metabolic processes, and GDM development in Malaysian Malay pregnant women with GDM.

Study’s strengths

Overall, the study design and methodology possess several strengths that contribute to the quality and credibility of the findings. The prospective cohort design, inclusion of control and condition groups, comprehensive assessment of variables, utilization of advanced molecular techniques, and use of validated measurement tools collectively enhance the scientific rigor of the study. These strengths increase the reliability and generalizability of the findings, making them valuable contributions to the existing knowledge on the gut microbiome, GDM, and associated factors during pregnancy.

Study’s limitations and potential sources of bias

While this study has provided valuable insights into the gut microbiome to GDM and pregnancy outcomes, it also acknowledged and explored the limitations and potential sources of bias that may have influenced the results. One potential limitation is the relatively small sample size of the study. The sample size in both the GDM and non-GDM groups may limit the generalizability of the findings to larger populations. A larger sample size would allow for more robust statistical analyses and uncover additional associations. Furthermore, the study was conducted at only two clinics in the southern part of Malaysia, which may introduce some site-specific biases and limit the generalizability of the findings to another setting or population within Malaysia and worldwide. Secondly, the study relied on self-reported measures for various variables, including dietary intake, physical activity, and lifestyle factors. Self-reported data are subject to recall bias and social desirability bias, which may impact the accuracy and reliability of the information collected. Thirdly, the study’s findings are based on associations and correlations rather than mechanistic explanations. The underlying mechanisms remain unclear, but the associations between the gut microbiome and various factors have been identified.