CHICAGO (AP) — An unusual legal challenge could upend the future of a Chicago ballot measure that would raise real estate taxes on luxury real estate sales to fund homeless services.

Such citywide ballot measures are rare in the nation's third-largest city, but other cities, including Los Angeles, have approved similar so-called “mansion taxes.”

A Cook County judge rejected the bill last month, but supporters of the initiative, called “Bring Chicago Home,” are hoping to see it overturned.

Early voting has already begun in Chicago for the March 19 primary, and the measure remains on the ballot pending a court case.

Here we take a closer look at the ballot measure and the issues surrounding it.

referendum

The referendum asks Chicago voters to support increasing transfer taxes on real estate valued at more than $1 million. This is a one-time buyer fee.

The City of Chicago's interest rate is currently 0.75% on all real estate sales. The proposal would overhaul the tax system, reducing the tax rate to 2% for estates worth more than $1 million, 3% for estates worth more than $1.5 million, and 0.6% for estates worth less than $1 million.

Most Chicago real estate sales are under $1 million, so the majority of homebuyers will pay less than that. According to analysis by proponents, about 95% of homebuyers will experience a reduction in the amount they spend on their home.

The median sales price in the Chicago area is about $350,000, according to the National Association of Realtors. Currently, the buyer will pay the city $2,625. Under the new structure, that would drop to $2,100.

Also, since this is a marginal tax, the increased rate only applies to the portion above $1 million. For example, on a $1.2 million property, $1 million would be taxed at 0.6% and the remainder would be taxed at 2%. Currently, the buyer is paying him $9,000, which will jump to $10,000.

revenue

Bring Chicago Home supporters estimate the changes will generate $100 million a year. The money would be reserved solely for homeless services such as mental health care and job training.

Chicago spends about $50 million in city funds on such services. Supporters say larger, dedicated funding sources would make a big difference, including for prevention.

“This allows us to move the needle in a way that we can't do now,” said Doug Schenkelberg, executive director of the Chicago Homeless Coalition.

The coalition says about 68,000 Chicagoans are experiencing homelessness, and racial disparities exist. About half are black. The definition of homelessness includes people who do not have a fixed address, whether they are sleeping on a friend's couch or on the street.

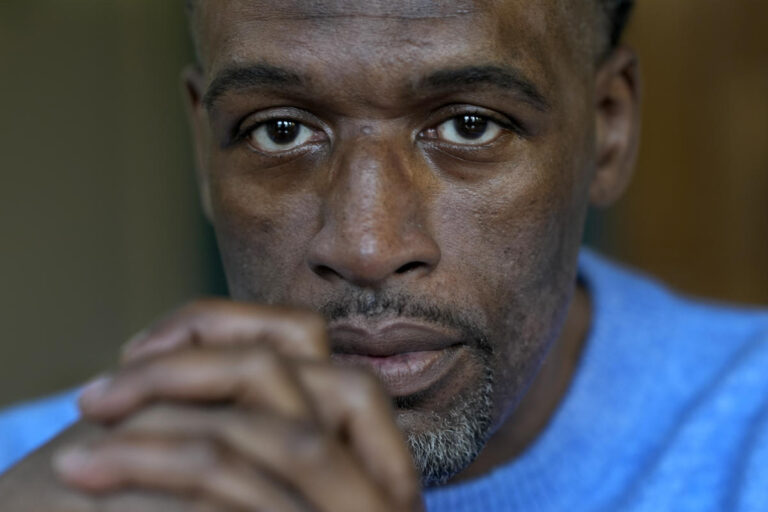

Brian Rogers, 50, struggled with homelessness for years after serving time for a theft conviction. It was difficult to find a job for him as he did not know where he would be staying.

“I feel like I'm off balance. I feel like I don't know when or where to leave or when to go to bed,” he said. “Such unstable situations create unstable decision-making.”

Approximately 17,000 people, or 25%, of Chicago's homeless population are children.

Electa Bey, 66, became homeless after her husband suddenly passed away from an illness in 2019. The couple were evicted. It took her months to find public housing for the four grandchildren she is raising.

His family took him in, but it was far from his children's school. They commuted more than two hours each way by public transportation.

“They couldn't play with their friends. Their homework wasn't always done and they would fall asleep on the train or bus,” she said. “Children are being very seriously affected.”

Opponent

Real estate groups argue the new tax will disproportionately impact commercial real estate as downtown recovers from the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

According to real estate services firm CBRE Group, the downtown office vacancy rate reached a record high of 23.8% at the end of 2023.

“I don't think it's right to punish one industry, real estate,” said Amy Masters of the Chicago Building Owners and Managers Association, one of the groups suing. “We need to think of other ways we can work together to support people who are unhoused.”

They call the tax an unfair burden on Chicagoans and argue the change will hurt business.

After filing the lawsuit in January, a Cook County judge sided with them in February.

legal battle

There isn't much legal precedent for voting questions in Chicago.

First, such a binding citywide voting effort is rare in the city. The last one was in 1993 and focused on new district maps, according to the Chicago Board of Elections.

Real estate groups say the proposed change violates state law because it requires voters to approve a tax cut and a tax increase at the same time.

But supporters question the way the lawsuit was filed.

The lawsuit names the Chicago Board of Elections, but says it is not a proper defendant. Instead, the committee that prints the ballots insists it should be the city of Chicago, which put the issue on the ballot in a November city council vote.

Judge Kathleen Burke rejected the city's intervention to allow the city to join the lawsuit. The city and the Board of Elections each appealed.

Meanwhile, the judge's written order says votes for the measure will not be counted, even though the question remains on the ballot. Those votes would be sequestered until the measure is approved by a court, even if approved after the election.

“Votes are still being counted,” said Max Biver, a spokesman for the electoral commission. “At this time, they are not aggregated, aggregated or published.”

For first-term Mayor Brandon Johnson, who supported the effort, the fate of the measure is in the balance.

“We strongly believe that the referendum is legally sound and that the final arbiter should be the voters of the city of Chicago,” Johnson's office said in a statement after the judge's ruling.

precedent

Other cities have raised so-called “mansion taxes,” with mixed results.

In 2019, voters in suburban Evanston approved an increase from 0.5% to 0.7% on sales over $1.5 million and 0.9% on sales over $5 million. The country's leaders report little impact on home sales, with incomes rising steadily each year and going to Black residents who have faced decades of racist housing practices. He pointed out that the money was being used as part of the compensation money.

Voters in Santa Fe, New Mexico, approved a referendum supporting an affordable housing initiative in November.

Los Angeles voters supported a similar measure in 2022. However, it has also faced legal challenges. Los Angeles' bill would impose a 4% tax on properties valued between $5 million and $10 million, and a 5.5% tax on properties valued over $10 million. Revenues were lower than expected, with some blaming a decline in luxury real estate sales.

Chicago advocates claim they studied these referendums to determine the city's proposed rate.

“This is a historic occasion,” said Jose Sanchez, a Bring Chicago Home spokesperson.