In this Ukrainian cohort, subjects belonging to the morning chronotype showed a unique eating pattern characterized by a more balanced diet and earlier timing of their last meal. Specifically, morning chronotypes reported decreased fat intake, increased carbohydrate intake, and decreased intake of animal protein-rich foods. Despite being older, morning people spent less time sedentary and active, and their SJL was smaller, indicating that they were more consistent with their body clock. Additionally, being a morning person was associated with improved metabolic parameters and predicted better overall metabolic health. Importantly, these effects remained significant even after accounting for confounders such as gender, age, physical activity, and BMI.

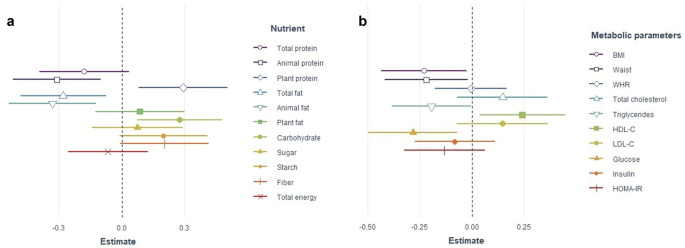

Consistent with previous findings, morning subjects in this study had lower fat intake and higher carbohydrate intake compared to evening subjects.11, 12, 13. Interestingly, lower animal protein intake was observed in morning chronotypes, which was not investigated in previous studies. Linear regression between continuous MEQ scores and nutrient intake models adjusted for confounders confirms the observed group differences. Lower intakes of fat and animal protein were consistently associated with higher MEQ scores and therefore morning chronotype. The results of the present study are partially consistent with her Mota et al., who reported a decrease in total protein intake in residents with high MEQ scores.14. The subjects' lower intake of fat and animal protein in the morning may be due to their lower overall intake of animal foods, which may be due to the difference between morning and evening chronotypes. This is supported by decreased intake of processed meat, eggs, and cheese.It was also found that young Japanese women who are morning people consumed less meat than women who were night owls, but the proportion of energy from protein showed the opposite trend.13. Regarding fish intake, no differences between clonotypes were observed, which is consistent with the findings of Sato-Mito et al.13 This is in contrast to the study of Kanerva et al.12. This discrepancy may be due to the low seafood intake of the current study population compared to national consumption rates.15. Additionally, higher carbohydrate, fiber, and bread intakes were observed for morning chronotypes, but these differences were maintained only for carbohydrates in the linear regression model after adjusting for confounders.MEQ scores were positively correlated with dietary fiber intake in Finns, as shown in a previous study12 and mexican11 On the other hand, no association was found in the Spanish population.11. Moreover, in a subgroup of the same Finnish population, a more detailed analysis showed that the positive association with fiber intake was only for the morning meal, but not throughout the day.16.Regarding grain intake, the results so far are somewhat contradictory.8. For example, some studies found that high intake of cereals and whole grains was positively correlated with MEQ scores.6,12. However, another study found no association with cereal, bread, or pasta.14. Previous studies analyzing indicators of healthy eating have shown that morning chronotypes adhere more closely to plant-based eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet.17,18 and has a higher Healthy Plant-Based Diet Index score, partially consistent with our results.19. The observed discrepancies between nutrient and food group intakes may be related to geography (particularly latitude) and therefore to climatic and cultural influences on dietary patterns, and the comparability of existing data is restricted. On the other hand, these discrepancies highlight the importance of assessing overall diet quality. Combining a food diary with a healthy eating index, because while food records provide valuable quantitative data, adherence to healthy eating patterns has stronger predictive potential than the intake of individual foods. This allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the relationship between chronotype and diet.18.

No differences in metabolic profiles were observed in between-group comparisons of the two clonotypes. However, as also observed by others, these differences were revealed by further multivariate regression analyzes adjusting for age, gender, and physical activity.20,21. Consistent with previous findings, the regression model of the present study found an association between higher MEQ scores and lower BMI.6,18,22triglycerides11,Blood glucose leveltwenty two. No association was found between chronotype and hypertension. In partial agreement with our results, a recent systematic review showed that evening chronotypes have higher concentrations of blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, triglycerides, and LDL-C, but in humans It was found that no significant differences were observed in measured values, arterial blood pressure, insulin, or homeostatic function.Model evaluation of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), total cholesterol, and HDL-CFive. In contrast to others, we observed a decrease in WC and an increase in HDL-C associated with morningness, but no difference in LDL-C. The association between morning chronotype and reduced odds of being metabolically unhealthy, reported in this study, supports recent findings of a positive association between evening chronotype and MetS. It is.6, 11, 20.

The mechanisms underlying the metabolic effects of diurnal dietary differences in different chronotypes are based on the circadian physiology of metabolism and the Zeitgeber effect of food.23,24. For example, meal-induced thermogenesis and insulin sensitivity vary throughout the day and decline in the evening.25,26a late dinner reduces postprandial lipolysis and oxidation of dietary fatty acids.27 In other words, the metabolic load of eating late is greater. Distinctive dietary patterns (i.e., meal timing and regularity, skipping of meals, and diurnal variation in nutrient intake) demonstrated in several studies also contribute to differences in cardiometabolic health between chronotypes. You may have.6,13,16,28,29. In the current study, first and last meal occasions were analyzed, and last meal intake was significantly earlier for subjects in the morning. Furthermore, it may be suggested that slow meal schedules may miscoordinate metabolic functions controlled by tissue clocks and central pacemakers controlled by environmental light-dark cycles. This misalignment is recognized as a reason for the high incidence of metabolic disease in shift workers.30 Also confirmed in a study using simulated night shift work31However, night chronotypes still need to be investigated. Therefore, we suggest that metabolic disturbances are less common in morning-type subjects due to a healthier diet and earlier opportunity for last meal.

Modifiable lifestyle factors such as physical activity and smoking vary by chronotype and can influence metabolic risk18,20.Morning people tend to be physically active6, 7, 18, 20, 32On the other hand, night owls have been shown to have a higher proportion of smokers.20,32. In our cohort, morning chronotypes spent less time sedentary, but the proportion of current smokers was similar. Disturbances in sleep parameters and circadian rhythms also contribute to the negative health effects of evening chronotype.Night chronotypes often experience poor sleep quality and sleep deprivation.3, 20, 33However, other studies have shown inconsistent effects of chronotype on sleep quality.7,34.Additionally, studies show that sleep duration and sleep adequacy do not alter the association between chronotype and metabolic disorders.32, 34, 35. In our study, sleep duration differed only on weekdays, with night type having shorter sleep duration and no effect on sleep quality.

Circadian rhythm deviations caused by work schedules are quantified using SJL, which reflects the mismatch between the biological and social clocks.Morning people had lower SJL in this study, which is consistent with previous findings.3,33. Increased SJL has traditionally been associated with an unhealthy lifestyle and a lower metabolic profile.36, 37, 38. Higher SJL was also associated with lower adherence to a Mediterranean diet, increased likelihood of skipping breakfast, and higher energy intake.36,38. However, the relationship between SJL, diet, and obesity is unclear among different chronotype groups.39. Therefore, the impact of SJL on the health outcomes of night owls remains uncertain. Other measures of circadian mismatch may be needed to assess circadian mismatch in these individuals.

This study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships. Additionally, assessment of individual chronotypes relied on subjective questionnaires rather than objective measures such as dim light melatonin onset (DLMO). Nevertheless, previous studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between the validated His MEQ and DLMO used in this study.40. Note that the median MEQ score (58 points) used to classify our sample falls on the borderline between morning and intermediate chronotypes. Therefore, our findings primarily compare his MEQ types of morning and intermediate chronotypes, and suggest that intermediate types are more likely to be metabolically It challenges the assumption of neutrality. Another limitation concerns the self-reported nature of sleep-related variables, introducing the potential for participant bias. Additionally, this study is limited by the small sample size. Future studies incorporating actigraphy or polysomnography may help overcome these limitations. Recognizing the multidimensional nature of estimating food consumption, we recognize that estimates of food consumption are subject to a variety of factors, not only due to methodological considerations but also due to factors such as differences in the actual nutrient content of foods and differences in individual responses to nutrients. We agree that errors may occur. Given these complexities, our results regarding associations with dietary intake should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, this study did not investigate diurnal changes in dietary composition, so further investigation is needed.

Despite these limitations, the present study has notable strengths. Including both middle-aged and elderly subjects with a wide range of metabolic phenotypes increases the generalizability of our findings. Using her weighed 7-day food diary for dietary intake analysis provides a more accurate assessment compared to methods such as FFQ or 24-hour recall. Additionally, energy-adjusted nutrient intakes were employed for between-group comparisons and regression analyzes to reduce external variations caused by individual metabolic rates.

In conclusion, our data provide evidence for distinct dietary patterns in morning chronotypes. The dietary composition observed in morning people is characterized by lower fat and animal protein intake and an earlier last meal opportunity, and is associated with higher chronotype scores and a more favorable metabolic profile. It may be contributing. Importantly, the associations between morning chronotype and lower BMI, waist circumference, fasting triglycerides and blood sugar levels, and improved overall metabolic health were independent of age and lifestyle differences. It happened. However, the underlying mechanisms of such effects remain to be elucidated. Longitudinal studies should investigate whether diet and feeding patterns mediate the metabolic effects of specific chronotypes. Furthermore, intervention studies using different dietary patterns that take into account meal timing and nutrient distribution are needed to elucidate the mechanisms and causal relationships of these associations.