However, offers to promote pharmaceutical companies such as Wegoby and Ozempic continued to arrive.

Then she saw fellow fat activists posting screenshots of similar emails they had received. They come from various marketing agencies and “medical spas” with names like Valhalla Vitality, Thoma Skin Therapy, and The Hills Beauty Experience, and they promote injectables for weight loss.

“That's when we started to realize that this could be very far-reaching. It's strategic,” she says.

Tovar was right. The email she received was part of an industry-wide strategy to sell injectable weight loss drugs through plus-size influencers. Tovar and her fellow activists began spreading the word on social media and speaking to the press.

Novo Nordisk has launched a marketing campaign aimed at the body-positive community as profits explode from sales of its medicines Wigovy and Ozempic. WeightWatchers is promoting his new WeightWatchers clinic, which focuses on injectable weight loss drugs, through paid promotions with social media influencers.

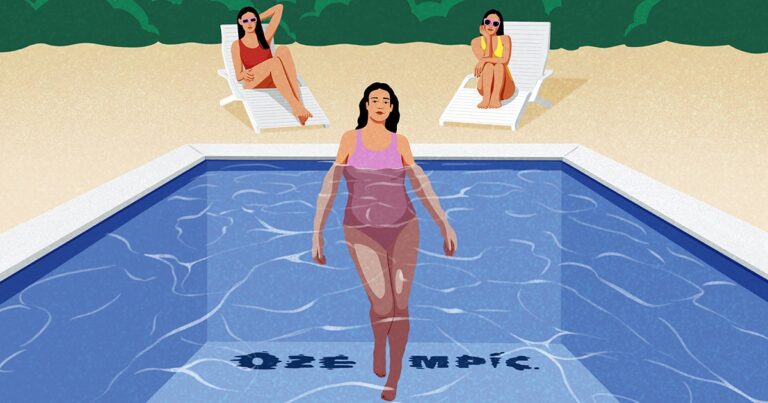

This push from the weight loss industry has created an ideological rift in the body positivity community.

Jessie Diaz Herrera, a plus-size certified fitness instructor, posted a video on Instagram saying she would throw her computer at a company that sells injectables if she received another partnership offer.

“When some of your favorite fat influencers start doing paid campaigns with stuff like this, it's because they've sold themselves to diet culture, well,” she says, using an expletive in the video. Ta.

A new marketing campaign asks plus-size internet personalities existential questions about what it means to be medically autonomous, self-love, and self-acceptance.

“There's a bit of a hornet's nest going on in the online body positivity community,” said Kara Richardson-Whiteley, CEO of Gorgeous Agency. We have been flooded with invitations for collaboration.”

Part of GORGeous Agency's business is connecting companies with body positive influencers. Richardson-Whiteley said the growing number of partnerships with injectable weight loss companies is raising red flags for some customers.

“This is an insult to people who have worked hard to come to a place of body acceptance, body appreciation, and debunking diet culture,” she said.

In April, WeightWatchers acquired telemedicine company Sequence, making it easier to connect users with semaglutide, a class of drugs known as GLP-1 drugs, Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzepatide, such as Mounjaro and Zepbound. Ta.

Since then, the company has partnered with influencers to promote WW Clinic, a new initiative that provides users with injectable drugs for weight loss.

In early January, Weight Watchers flew a cadre of influencers to a Los Angeles hotel for an event called “GLP-1 House.” It featured gift boxes, lectures, an appearance by RuPaul's Drag Race contestant Kim Chi, and plenty of opportunities for photos, videos, and collaborative content creation.

Jake Beaven-Parshall and Kiki Monique are two influencers who have joined the GLP-1 house. Both had already documented their use of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss on their Instagram accounts before Weight Watchers approached them.

According to Beaven-Parshall and Monique, they were paid to create content from the GLP-1 house. WeightWatchers also covered his travel and lodging expenses, and he waived his WeightWatchers membership fees for three months. In both cases, they had already received his GLP-1 drug through their own insurance.

Beaven Parshall describes her experience at GLP-1 House as “incredible” and estimates she has received more than 20 DMs from followers interested in the WW Clinic program.

“There's a lot of stigma around these drugs. It's the easy way out, Kardashians. [are] That’s what we’re doing,” he said. “So I think it's important to humanize it and educate people and show people's real journeys.”

Monique said the response to her GLP-1 content has been largely positive. “Hire @weightwatchers 🙋🏻♀️🙋🏻♀️🙋🏻♀️🙋🏻♀️ She's 150,000 times on Tik tok!” one user wrote on a video of her preparing for the GLP-1 house. I replied with a comment.

Monique also lost followers and received some angry comments. She was surprised at how harsh he was.

“Body positivity is about being comfortable with who you are,” she said. “I started because I wanted to get fit. I don't mind staying a size 18 as long as my back doesn't hurt.”

Amanda Tolleson, Weight Watchers' chief marketing officer, said in an emailed statement that the company's intention is to work with influencers to “bring healthcare into the living room and create a safe space free from bias and stigma.” The goal is to help them and their followers “regain health by providing the following.” , are embarrassed to talk about their medication experiences. ”

Fat-positive author, speaker, and researcher Ragen Chastain sees danger in this approach. “Influencers are not doctors,” Chastain says. “When pharmaceutical companies pay influencers to promote their medicines, they have inherent ethical problems because the influencers cannot be expected to understand the scientific issues of the medicines. It’s not something you do.”

The origins of the fat-tolerant movement date back to at least 1967. At the time, activists held a “fat in” in Central Park, where protesters burned diet books and photos of model Twiggy. Two years later, NAAFA, now known as the National Association for the Advancement of Fat Acceptance, was founded.

Today, the movement is primarily concerned with changing laws and structures that discriminate against fat people. “Body positivity,” on the other hand, tends to focus on loving your body and expanding standards of beauty at all sizes.

Some marketing materials from Novo Nordisk, the company that makes Ozempic and Wegoby, reflect the buzz of body positive online communities.

On “It's Bigger Than Me,” a scripted Internet talk show produced by Novo Nordisk, actor Yvette Nicole Brown challenges guests, including plus-size influencer Katie Sturino and media personality Ashley Marie Preston, to promote body positivity. It still guides you into familiar territory: lamenting the lack of size. Inclusion in fashion, encouraging people to stop criticizing celebrities' bodies on the red carpet and learning to accept yourself at any size.

However, it also cites “reverse body shaming” of people for losing weight and the “limitations of the body positivity movement when it comes to certain health issues”. In the episode titled “Defending Your Right to Lose Weight,” Preston describes herself as “an active member of the body positivity movement” before considering losing weight due to health issues such as acid reflux and sleep apnea. He said that he had “sunk it to the depths”.

Many people in the online body positivity community have expressed concerns about the safety of injectable drugs used for weight loss, citing cases of gastroparesis and questions about what happens if patients stop using the drugs. There is. Others question the validity of obesity as a medical diagnosis and the assumption that a higher BMI necessarily indicates poorer health.

In an emailed statement, a representative for Novo Nordisk said the content of “It's Bigger Than Me” can coexist with messages from other body positive movements.

“We are not here to disparage body positivity or in any way undermine the progress we have made in inclusivity as a community,” the representatives wrote. “In reality, two truths exist: Obesity can affect health, but the discrimination, stigma, and shame experienced by people living with obesity because of their weight is also very real. .”

But in some body-positive communities, advocating weight loss and having a healthy relationship with your body are not compatible.

Sarah Chiwaya, a plus-size fashion designer, said: “There's so much value in having a safe space to escape all the body shame and pressure to lose weight. I know this firsthand, so I try to protect it very much.” Blogger and consultant based in New York City. She said, “I don't want to see people use this community for their own purposes and then discard us.”

A few weeks ago, in Chiwaya's hometown, posters advertising the WW Clinic began appearing on downtown street walls. Professional care. ”

Chastain doesn't think it's possible to simultaneously reduce weight stigma and eliminate obesity through diets and weight-loss drugs. “That's not true,” she said. “Eradication is a stigma.”

Ending weight bias has been a hallmark of the fat acceptance movement since its inception, but Tigress Osborn, executive director of the National Fat Acceptance Association, believes these companies are focusing on the wrong thing.

“They tend to talk about how weight bias keeps people from getting treatment, they don't talk about how weight bias keeps people from getting treatment,” Osborne said.

In a clinical trial with a sample size of 122 physicians in Texas, weight bias was correlated with less time spent with larger patients. Another study found that physicians' weight bias was associated with a reluctance to offer certain screenings to larger patients.

Patients' fear of having their weight judged by their doctor is correlated with avoidance of preventive medical care such as mammograms and physical exams.

Last year, Novo Nordisk sponsored two documentary projects focused on weight stigma: the feature film Embodied and the documentary series Thick Skin.

“It's good to encourage people to find a doctor who treats them with humanity, empathy and respect,” said Erin Standen, a researcher at the Mayo Clinic who studies weight bias. “But when Nordisk talks about weight bias and prejudice, it makes me wonder what their motivations are.”

Rebecca Poole, a professor at the University of Connecticut, has spent 20 years studying weight bias and proposing strategies to reduce it.

“The truth is, I'm not for or against medication,” Pule said. She also revealed that she has received funding in the past from Nordisk and Lilly for work and speaking engagements on weight stigma and weight bias dating back to before the launch of her weight loss injectable drug. .

Pule is less concerned with an individual's choice to use drugs to lose weight than with how society responds to the needs of larger bodies. She referenced a law passed in New York City in November 2023 that prohibits employment discrimination based on perceived height and weight. Such laws remain exceptional.

“There's a lot of attention to discussing these treatments,” Pule said. “We could channel all that energy into building more respectful societies and communities for people of all sizes.”