I I just bought a new car (for me). Neither her husband nor I have bought a car in over 25 years, so you can imagine my excitement when we found out we could now receive her Sirius radio with over 100 stations.

I love listening to music. That's the story I heard from my mother, whose most precious possessions were a radio and a record player. Today, I see people young and old wearing tiny speaker pods in their ears and getting lost in their own world of music and wonder. What was it like over 100 years ago when you had to create your own music?

There were no televisions or radios for families to surround themselves with at night for entertainment, and no Victrola to play dance music. During the holidays, instead of tuning in to Dolly Parton's Christmas special or watching “The Muppet Christmas Carol,” people had to come up with their own entertainment. Enter the world of Waterloo Piano & Organ Company and Music Academy.

In the 1800s, musical instruments of all kinds were considered household necessities. The Waterloo Organ Company was founded by him in 1861 and began manufacturing parlor organs and melodeons, a type of accordion. The company began manufacturing pianos designed by talented architect Sebald Mennig in 1889, when Malcolm Love created the blueprints for his pianos, which were known nationally for the quality of their tone and pitch.

In 1903, the company was purchased by William and Chauncey Becker and William C. Vaux and renamed the Vaux Piano Company. The company began manufacturing Vaux variable pitch pianos, one of which is owned by the Waterloo Library Historical Society. The factory remained in operation until World War II.

One of the organ and piano factories was located on the east side of Church Street, just north of Main Street. There was another factory on Washington Street that later became Moore's Furniture. The demand for high-quality equipment kept the factory floor busy.

“Beloved” Music Academy

The first Malcolm Love piano was purchased by Vanadja B. Knight. That piano is now on display at the Terwilliger Museum at the Waterloo Library and Historical Society. One of his famous performances on the piano took place at the Academy of Music, beloved of Waterloo society.

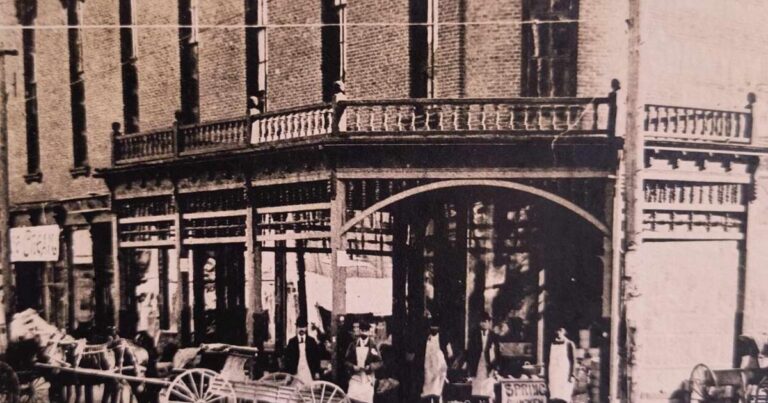

Built in 1868 on the site of the current Waterloo Post Office, the Academy was designed as a music hall to showcase concerts, plays, and oratorios produced and performed by Waterloo residents. According to John Becker's History of Waterloo, it had an excellent dance floor and was a popular venue for large gatherings.

Church groups, school groups, and social groups provided entertainment and diversion by putting on shows for the community. At Waterloo Union School, the Academy held an annual speaking competition where students performed a variety of dramatic readings in a bid to win the coveted ribbon.

Waterloo's early population consisted of large numbers of German immigrants. This was reflected in the Academy's 1883 program of “Grand Concertos” written in German. A note on the back says, “The spinet does not appear because Jedediah Stygitode will not lend it to us.” Fortunately, “Dr. S.R. Wells kindly lent me a pianist.'' It also notes that “unscrupulous frivolous persons will be apprehended by Special Constable Hudson and made to sit in the woodshed.'' has been done.

The Academy of Music attracted national attention when General Tom Thumb, the dwarf made famous by PT Barnum, and his wife, the “infinitesimal” Minnie Warren, visited Waterloo for a performance. Plays performed at the Academy included “Jane Eyre,'' “Esmeralda,'' and a farce called “That Rascal Putt.''

Sadly, a fire broke out in the early hours of September 17, 1904, marking the end of the Academy. The fire was so hot that no one from Waterloo's south side was traveling north on Washington Street. If a fire had broken out during the performance, many people would have died because there were insufficient exits and ventilation. At the same time, the organ and piano factory was destroyed by fire. These fires were a common occurrence, given that turpentine, thinner, and varnish were stored in open vats, and smoking cigars was a common pastime among factory workers.

But the real demise of Malcolm Love and Vaux's piano came with the availability of radio and television. People can enjoy turning the knob anytime and anywhere.

Pianos cannot now be transferred. It breaks my heart to see these works of art thrown away on the garbage heap. On the plus side, there's music everywhere you go now, and I still smile when I think of my mom and dad dancing in the living room on Sunday nights watching Ed Sullivan.

Pamela Becker is a former history teacher and researcher/archivist at Waterloo Library and Historical Society.