Credit: Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain

× close

Credit: Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain

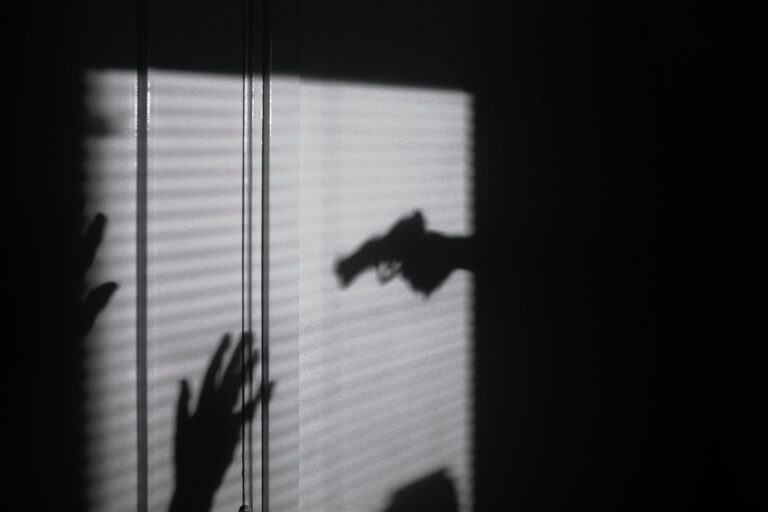

]On October 28, 2003, Barcelona was the scene of a tragic incident that had repercussions in the Spanish port city and beyond.

That Tuesday afternoon, 15-year-old Ronny Tapias was shot dead by a Barcelona gang as he left school, mistaking him for a member of a rival family.

conflicting factions

The killing of Tapias, a Colombian national, sparked a public outcry. Concerns were raised about the threat posed by Barcelona's gangs and the influence of immigrants from Latin America, the birthplace of both clans involved in the Barcelona feud.

“The extensive media coverage has caused a real moral panic,” said Carles Faixa, a professor of social anthropology at Barcelona's Pompeu Fabra University.

Ms. Faisha helped shape the city's response to the incident through a pioneering program that tackled gang violence by pursuing mediation rather than enforcement.

This program, known as the 'Barcelona Model', formed the basis of an EU-funded research project to investigate the international dimensions of gangs and the role of mediation in combating violence in the 21st century.

Mr. Faixa led the project called TRANSGANG for five and a half years until mid-2023.

musical touch

Barcelona's response to this murder included bringing together the city government, the police, and most importantly, the two rival gang factions.

Music was the first means of dialogue between the two clans, Faixa said, and was a joint rap festival.

A youth association was then established to give the young people involved their own space and general training opportunities such as life skills and conflict resolution.

“That opened the door and we got to know each other,” said King Manaba, a former Barcelona-based gang leader who became involved in the mediation process after Tapias' death. .

Over time, violence between the two warring gangs decreased.

Manaba then collaborated with Faixa under TRANSGANG and sought lessons not only from Barcelona, but also from Rabat in Morocco and Medellin in Colombia, where gang mediation had also been successful.

Young people who join gangs typically do so to escape socio-economic troubles and gain recognition from their peers, Faixa said, but these factors make mediation a more effective approach than repression. It is said that there is.

“Through mediation, they see themselves as people who can contribute something,” he says. “It is possible to redirect gangs in a more pro-social way. Mediation is essential to fostering a more positive and inclusive future for young people around the world.”

Gangs have been a growing phenomenon for more than a century and now exist in most societies around the world, often operating across national borders. As public awareness of the gang epidemic increases, so does the need to refine policy approaches.

lessons learned

TRANSGANG examined the evolution of transnational gangs, comparing the approach of Barcelona, Rabat, and Medellin with more punitive responses to gangs in other parts of Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

The project found that coercive and exclusionary policies can create negative public perceptions of gangs and exacerbate socio-economic problems.

“When the only way to get to gangs is through the police or prison, this not only suppresses gangs, it turns gangs into criminal organizations,” Faixa said. “When we attack gangs, the result is that gangs become a problem with no solution.”

The project found that when mediation occurs, public opinion becomes more nuanced, social cohesion increases, and crime decreases.

Insights from this project are now informing approaches to gangs in other cities in Spain, urban centers in Italy and Sweden, and abroad through the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

Faisha himself is working on a book called “Young Lives Matter,'' a collection of gang members' life stories.

gang guest

Dennis Rogers, a professor of anthropology at the Center for Conflict, Development and Peacebuilding at the Geneva Graduate School in Switzerland, also believes a new attitude is needed in dealing with gangs.

And like Facia, Rogers took a pragmatic approach to the challenge.

Rogers has been researching gangs since he was assaulted by a gang while living in Nicaragua in the 1990s. Embracing the principle of “if you can't beat them, join them” and the possibility of his unique research access, he then threw himself into a Nicaraguan gang.

Initially, he was embedded in it for a whole year. Over the next few years until 2020, he returned to Nicaragua many times, staying with his gang for up to three months.

Rogers said these experiences have made him pay attention to an important global phenomenon that can take different forms depending on the region.

“Gangs are global,” he said. “At the same time, they are highly variable and unstable, with unique social dynamics.”

Rogers said gangs can go dormant after months or years, evolving into criminal organizations or even morphing into more cultural or economic organizations. But little is known about why one path favors another, he said.

Rogers leads another project into the gang. The project, called GANGS, has been running for five and a half years, until mid-2024, and has investigated how gangs emerge, operate and develop.

The researchers studied gangs in cities such as Marseille, France, Naples, Italy, and Algeciras, Spain, as well as urban areas in Nicaragua and South Africa, where gang violence has escalated since the 1990s.

Wisdom that goes beyond common sense

One of the conclusions of the entire project so far is that gangs are fundamentally embedded in the social fabric.

Another conclusion is that gang membership can have a variety of long-term consequences for both individuals and communities, but not all of them are negative. Rogers said these reflect broader societal factors, with much of the gang-related violence stemming from the influence external perceptions and interventions have on gangs.

In this respect, the team challenges traditional public perceptions of gangs and their impact on society.

For example, in Marseille, widely considered the epicenter of gang violence in France, researchers found that most local households have more pressing concerns, such as housing, health, education, and employment. I discovered that.

Mr Rogers warned against “stereotypical representations” of gangs and their violent instruments, saying overly simplistic views increased the risk of counterproductive policy responses.

“They can lead to authorities acting a certain way towards the city and not recognizing the real problem,” he says.

Rogers said that in Marseille, the stigmatization of gang-influenced areas has led to heavy-handed policing, exclusive urban development and cuts to public investment, particularly in educational infrastructure.

From gangster to poet

For Rogers, the complex nature of gangs and their members' ability to change course is epitomized by Yusuf Kamara, a former Sierra Leonean gang leader.

During Sierra Leone's 10-year civil war that lasted until 2002, Kamara left her rural village at the age of 16 to try her luck in the capital, Freetown. There he joined a feared local gang and became its boss.

Then one day in 2017, after overhearing a conversation between friends enrolled in a poetry course, Kamala discovered a new passion. He began writing poems on his cell phone and sharing them online through his YouTube.

With support from local arts organizations, Kamala rose to fame and began competing in prestigious international poetry competitions. He calls himself “Paper Poet Gaz.”

Kamara also founded Slums to Career, an organization that helps transform the lives of young people surviving on the streets of Sierra Leone.

His story was collected by a gang team member named Dr Kieran Mitton from King's College London, along with the stories of 31 other current and former gang members from around the world, targeting both populations. It is scheduled to be part of a forthcoming book on the project. general public and academic audiences.

“I wanted to tell my story,” Kamara said of her planned book. “If 10 people change, it means a generation has changed.”