This is the second installment in an occasional series about cold cases investigations in Cedar Rapids and Linn County.

CEDAR RAPIDS — Dianne Martin doesn’t remember much of that October day in 1959 because she was only 7 and in bed with a headache, fever and swelling of the neck and face — a bad case of the mumps.

“I remember my dad kissing me on the forehead and saying ‘Punkin, I hope you’re going to feel better today,’” she told The Gazette during a phone interview. “He always called me Punkin. If Dad called me Dianne, I knew I was in trouble.”

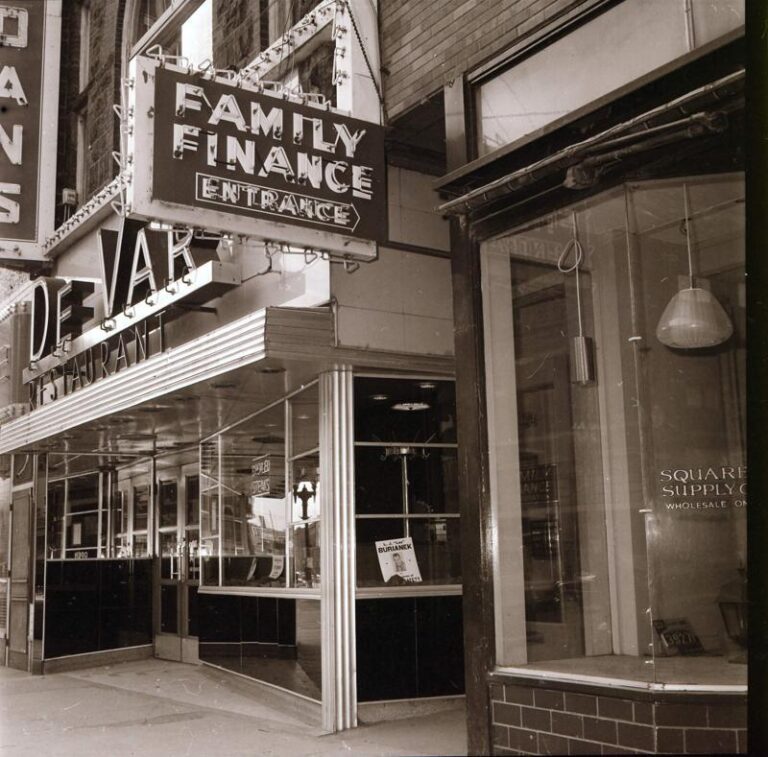

Her father, Frederick “Fred” Leonard Coste, 47, went to work Oct. 15, 1959, at the Family Finance Corporation in downtown Cedar Rapids. Her mother, Betty, went to the dentist for a tooth extraction. She was at home with her grandmother, Louise Coste — Fred’s mother — who lived with the family.

After leaving the dentist office, her mom had to pick up a prescription and decided to walk over to Fred’s office at 312 Second Ave. SE, which is now a parking garage.

When Betty got near the office, she saw police cars with flashing lights. Officers stopped her and wouldn’t let her go inside. She didn’t know what was going on.

“I really don’t remember much,” said Martin, now 71 and living in Alabama. “I was so sick. I’m not sure it registered at the time. My grandma fell apart when she heard about my dad. I remember my mom was upset but she was a strong woman. She had to be for my grandma.”

Martin never thought that kiss on her forehead would be the last from her father. And she never thought his slaying would turn into an unsolved cold case 64 years later.

“I wanted for whoever did this to be found,” Martin, becoming emotional, said. “I wanted him to burn in hell. I wanted him to suffer, and sometimes I still do.”

Details of crime

Fred Coste was discovered by two loan applicants, Thomas McMurrin and Donald McSpadden, about 11:35 a.m. that day, on his back surrounded in blood, Cedar Rapids police Investigator Matt Denlinger said in reviewing the original cold case file.

The two men went downstairs to the De Var Diner, which was below the office, and found a police officer, Donald Hollister, who contacted detectives, George Matias and Roy Walker. They arrived about 11:55 a.m. at the scene with an identification officer.

Denlinger, a member of the department’s Cold Case Unit, said there was evidence of a struggle in one of the cubicles where Coste was likely consulting with a client. The office made small loans and kept cash on hand.

“The table had been pushed back against the wall with a chair behind it,” Denlinger said. “There was a manila folder that Fred was looking at with a customer’s name on it — he was clearly a person of interest. The detective’s notes indicated there was “probably an argument over an application for a loan that Fred had turned down.”

Coste was stabbed in the chest six times with a “heavy object,” Denlinger said. One of those stab wounds punctured his heart, according to the coroner.

The detectives also found “partial bloody hand prints” on a drawer behind the counter and it was determined that $258 was missing from the cash drawer.

The person of interest’s file showed he had taken out a loan for $151.58 on Sept. 25, 1959, and there were what appeared to be blood droplets on the account sheet.

Who was Fred Coste

Denlinger said he is in “awe” of how thorough the detectives were and how quickly they collected evidence and created a “victimology” — a deep background report — on Coste.

When investigating a case, Denlinger said detectives want to look at the victim’s background to see if the crime happened because of the circumstances surrounding the victim. But there was nothing in Coste’s life or background that would lead detectives to an obvious killer.

Coste grew up in Little Falls, N.J., and served in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1946, which included World War II. Before serving, he sold Pontiac cars for a short time, then worked for National Life Insurance and then for a loan company in Atlanta, according to the case file.

No problems in the military. No disgruntled ex-girlfriends, investigators determine.

He started working for the Family Finance Corporation in 1949, then was called back to the military — this time for a stint in U.S. Air Force in 1950. He then returned to Family Finance in Charlotte, N.C., as a manager.

Coste had been robbed in the past, Denlinger noted. When he transferred to Baltimore, Md., a man in 1953 robbed that office at gunpoint. The suspect was captured within minutes and identified by Coste. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Coste was transferred to manage the Cedar Rapids office in 1958 and had been here only about 14 months before the fatal assault, Denlinger said.

A former secretary, who worked at the office the month before the slaying, spoke “highly” of Coste. But when the killing happened in October, he didn’t have a secretary in the office.

Coste would occasionally stop by a tavern, usually “Sammy’s” on First Street, for a beer and then go home, Denlinger said. There were no reports that he was a gambler or had any work issues. His wife would stop by the office in the afternoons to help.

The two men who found his body, McSpadden and McMurrin, agreed to take a polygraph — lie detector — test, which seemed to be a typical police tool back then to rule out suspects but “rarely” used today, Denlinger said. McSpadden and McMurrin passed and weren’t considered suspects.

A timeline was quickly established, Denlinger said. At 11:15 a.m., a Mrs. Charles Kenke reported she talked to Coste on the phone and his body was found at 11:35 a.m. — which left about a 20-minute window for the fatal attack.

Possible suspect

The customer whose file was found on the floor near Coste’s body was called by police within an hour of the homicide. He lived in the Cedar Hills neighborhood.

The “Cedar Hills man” — as Denlinger dubs him — denied being at the finance office. But when officers showed up at this house, he admitted to stopping by to inquire about a loan. He said this happened about 11 a.m., and he was told to bring back his wife to co-sign for the loan, which the detectives doubted was true. He also denied knowing anything about a homicide there.

The detectives couldn’t verify his timeline and obtained a search warrant for his home and vehicle. In the house, they found a handkerchief with what appeared to be blood stains. In the car, a bone-handled knife with blood stains was recovered.

T.C. McDermott, the identification officer, flew with the items for testing to the FBI lab outside Washington, D.C., within 24 hours of the homicide. The testing was completed within five hours, which is unheard today, Denlinger said. It usually takes weeks or months with backlogs at the state crime lab.

However, the test showed the blood on the knife wasn’t human. It was from “some sort of rodent.” No link was made between the potential suspect and the evidence.

The Cedar Hills man took a polygraph but the results must have been questionable. Denlinger found notes from a follow-up discussion with a University of Iowa professor about administering “truth serum.” That had apparently been used by other agencies at one time, but the professor said it was unreliable and it wasn’t done.

The possible suspect was released due to lack of evidence.

Denlinger said there were many notes on canvasses downtown and follow-up interviews, but no real leads. Detectives even had checked out any possible suspects who were traveling with the Clyde Bros. Circus out of Oklahoma that had been performing on May’s Island the day before, Oct. 14, 1959.

An interview with another former office secretary, Pat Thompson, gave the detectives another possibility for a murder weapon. She recalled that there had been a different letter opener than the one found in the office, and it was bigger and made of copper or dark in color.

Denlinger said it was unclear in the notes if investigators thought it might be the “heavy object” used to stab Coste, or if that letter opener had just been replaced by a new one. The larger letter opener was never found.

Daughter’s memories

Martin, a retired social worker, said her mother was so upset in the days following her dad’s death that they left for Chicago and stayed with a relative. She recalls spending a “beautiful” day on the lake with a cousin before going to Atlanta, where her mother’s parents lived.

That’s where they buried her father. Her mom didn’t want to go back to Cedar Rapids. It was too painful. They lived in Atlanta for a few years.

She remembered the military funeral for her dad, who was a staff sergeant during his service. She recalled hearing Taps and the flag was presented to her mother, which Martin received after her mother died.

Martin doesn’t recall much from her short time in Cedar Rapids. She remembers their house was at the top of a hill down the street from Quaker Oats. She remembers not liking the “awful cold” winters.

“My dad would call my mom and tell her to ‘put another sweater on Punkin, it’s 2 degrees out,’” Martin said.

She remembers her dad as “soft-spoken, mild mannered, very tall and handsome.” He never talked about his time in the war, her mom told her. She knew he was an airplane mechanic in the service, serving in France and Germany and later stationed in Georgia.

She has memories of helping her dad wash the car, which she loved, and playing at the playground and her dad pulling her down the slides.

Her dad loved their puppy, Puddles, a shepherd/collie mix. She learned how to walk holding the dog’s tail. Puddles died after getting bitten by a snake. She said her dad was “devastated.”

Coste would go out and collect on loans on the weekends and he would take his wife and daughter along.

“I remember going to the Amana Colonies for lunch and going to the diner downstairs from the office,” Martin said. “The popular song ‘Volare’ (a hit in 1958) was my favorite song and Dad knew the diner owner and he would rig up the jukebox to play it when we came in.”

Her mom always told her what a good man he was and her how much he loved his daughter.

“’The sun rose and set on you,’” her mom would say.

Martin said she has thought over the years how different her life would be if her dad hadn’t been killed. “But I might not have my three fabulous children and three grandchildren. I don’t know.”

As Martin got older, she had such empathy for her mother because “Dad was the love of her life” and it was heartache to lose him in such a brutal way. Her mom suddenly was a single mom with a young child to support.

She worked different jobs over the years, including an optical retail store and in the medical records office of a hospital. Her mom never remarried. One time, she had a boyfriend when Martin was a senior in high school and thought about getting married.

“I asked her if she loved him and she said, ‘I loved your dad,’” Martin said. She didn’t get married.”

Coste met his future wife when he was selling insurance door-to-door in Atlanta. After he left, Betty told her mom she was going to marry that man.

They dated for less than a year and got married in 1939, Martin said. He wanted to buy her a diamond but she didn’t want one. Betty wasn’t a “ring person.” Instead, she settled on a rose gold watch and wore it for many years.

Martin said she remained close to her mother even after leaving Ohio, where her mother stayed. Betty Coste died in 1982 from cancer.

“She was an amazing, strong woman,” Martin said. “She had to be mom and dad for me.”

Recent work on cold case

Denlinger said that in 2007, there was big push in the department to look at Cedar Rapids cold cases. Specimen and hair samples from Coste had been collected for future testing, and now-retired Investigator Doug Larison sent those in for further testing. But nothing significant was discovered.

Larison followed up on the “Cedar Hills man” and learned he was living out West. In 2013, retired Capt. Jeff Mellgren, who worked as a volunteer for the Cold Case Unit, traveled to his home for an interview. The man was 83 years old at the time.

His story had changed some from 1959. He said he was given “truth serum,” which didn’t happen, according to the case file. Mellgren was hoping for a confession but didn’t get one.

Denlinger said it was difficult to decipher from the case notes if this man was lying or maybe, based on his age, having memory problems.

Last year, the unit took another look at this case and realized investigators didn’t have a good DNA profile from the victim to use for comparison in further forensic testing, Denlinger said. The specimen samples collected from Coste in 1959 were tested in 2007 but were “too degraded to yield any results.”

Denlinger set out to find Coste’s daughter to collect DNA from her, but unfortunately all the reports listed her only as “7-year-old daughter.” He searched for an obituary of Coste but only found a burial location on Gravefinder.com.

He called the cemetery in Atlanta. An employee there found a note in Coste’s file from 1982 about a woman, Dianne Martin of Columbus, Ohio, who said she was his daughter and wanted to sell the plot next to his.

Next, he called the Columbus Police Department’s Cold Case Unit for help, and officers there found out Martin had moved to Alabama.

Denlinger eventually found her phone number and coordinated with Alabama police to take a DNA sample from her. Those were sent to him, and he provided them to the state crime lab in Ankeny. Martin’s sample is being used for comparison to the profile developed from the blood evidence found on the floor at Family Finance in 1959.

Denlinger said he didn’t know if the testing would show anything. At this point, he is trying to get answers for Martin. He’s fairly sure he has identified the killer, but is doubtful it will lead to an arrest. All the officers from the case are dead and there’s no living witnesses to testify at a trial. And the suspect, if still alive, may never confess.

This case is much different from 18-year-old Michelle Martinko, who was killed in 1979 and went unsolved for 39 years until 2018. Denlinger had DNA evidence of the killer, Jerry Burns, and the witnesses needed for trial were still alive.

Martin said she needs closure, in whatever form that happens. If she finds out the killer is dead, it might give her that.

“I still have hope,” Martin said. “I hope Matt will find something that will blow it wide-open.”

Comments: (319) 398-8318; trish.mehaffey@thegazette.com