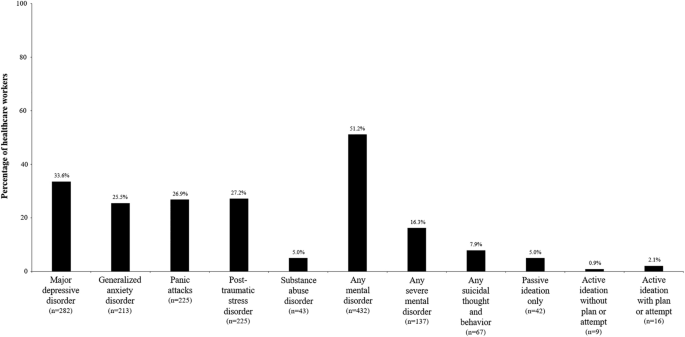

The emergence of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has created a global public health emergency, posing significant psychological challenges to global health systems, especially during the early stages of the outbreak. Masu.32. The results obtained from the present study demonstrate that current mental disorders and suicidal ideation were significantly reduced in a large sample of healthcare workers at the October 12 Hospital (Spain) during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This indicates that the prevalence of the disease is high. MDD symptoms were most commonly reported, followed by GAD, panic attacks, and PTSD. Additionally, health care workers with lifelong mental disorders were observed to have significantly higher rates of negative mental health outcomes. Certain other variables were found to increase the risk of developing mental disorders, including gender, age, job title, and direct contact with infected patients.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers are facing unprecedented circumstances that are taking a toll on their mental and physical health.33. Their important tasks require them to make difficult decisions under extreme pressure, which puts them at higher risk of developing mental health disorders.34,35.Previous studies documenting the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the mental health of healthcare workers are consistent with the findings presented here.15,16,36,37,38,39.A survey conducted by the British Medical Association in May 2020 found that 45% of UK doctors are experiencing anxiety, depression, stress and other mental health problems due to the coronavirus pandemic. It has been shown36. In Spain, another survey conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 (May 2020 to September 2020) found that 43.7% of 2929 primary care professionals (95% confidence interval) is[CI]= 41.9–45.4) Screened positive for possible mental disorder37. Published studies that assessed mental burden on healthcare workers generally reported symptoms of anxiety, depression, insomnia, or distress.38. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety was 8.9–50.4% and 14.5–44.6%, respectively. A systematic review and meta-analysis including data from 70 studies and 101,017 healthcare workers found pooled prevalence rates of 30.0% for anxiety, 31.1% for depression and depressive symptoms, 56.5% for acute stress, It was revealed that 20.2% of post-traumatic stress. Sleep disorders were 44.0%39. Another systematic review and meta-analysis including 12 studies on the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in Asian countries found that the overall prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress was 34.8%; It is reported that 32.4% and 54.1%.Each40.

The MINDCOVID study in Spain was a multicenter observational trial that aimed to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers during the first wave.15,16. Consistent with our findings, almost half of the workers surveyed (45.7%) currently exhibit some form of mental disorder, and 14.5% have tested positive for a disabling mental disorder. Ta.15. The most frequently reported possible mental disorders were current MDD (28.1%), GAD (22.5%), panic attacks (24.0%), PTSD (22.2%), SUD (6.2%), and STB (8.4 %)was. Other reported prevalences were passive ideas (4.9%), active ideas without plans or attempts (0.8%), and active ideas with plans or attempts (2.7%).15,16. Comparing our current results (single center) with those of the multicenter national MINDCOVID study:15, the prevalence of all possible psychiatric disorders, MDD and PTSD, is higher (Supplementary Figure 1). The observed differences may correspond to different causal relationships in Spanish hospitals in the first wave. Indeed, the pandemic has raised potentially traumatic moral and ethical challenges that put health care workers at risk of causing moral injury (e.g., deciding who to put on a ventilator in a situation where one does not exist for everyone). (e.g. select whether to do so).41,42. Although moral injury is not yet considered a mental disorder, it is thought to be related to PTSD due to its symptomology and etiology. Because both can be her two different reactions to trauma.41,42. Therefore, this high prevalence of PTSD may be due to health care workers' exposure to these moral stressors.41,42.

Regarding potential factors associated with the likelihood of mental disorders, our study pointed to higher vulnerability of younger people (18 to 29 years), women, and people with lifelong mental disorders (p< 0.05).Sociodemographic factors such as gender and age were previously associated with higher risk38.Several studies analyzing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare workers have found that female gender is associated with an increased risk of mental disorders.43,44,45,46,47. A recent meta-analysis including 401 studies conducted by Lee et al. reported that women were more likely to have mental health disorders, particularly depression, anxiety, PTSD, and insomnia.48. Potential response biases (e.g., men may have more difficulty recognizing and expressing psychological distress) and various biological, social, and demographic factors may explain these differences. Multiple explanations or mechanisms have been proposed, including factors.49,50. Therefore, age and gender appear to be risk factors, but this should be considered with caution. Additionally, the presence of a previous mental illness has been identified as a predictor of other mental health problems such as depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.51. Additionally, some studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic may be having a negative impact on current mental disorders.52. Given that all healthcare workers are at high risk of developing or worsening psychiatric symptoms, healthcare workers with previous or current mental illness are more vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. It would have been.

Limited availability of personal protective equipment, continued exposure to infected patients, mortality rates, lack of specialized treatments, and overwhelming workload are also factors that contribute to the development of these psychological problems.53. Additionally, health care workers' growing anxiety about the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is compounded by misinformation spread during the first wave of the pandemic and concerns that they could infect their partners and family members. Possibly related.43,54. Furthermore, it was observed here that some occupations, especially auxiliary nurses, are at higher risk of mental disorders (p< 0.05). Maunder et al.55 A study of trends in burnout and psychological distress among health care workers from fall 2020 to summer 2021 also found that nurses reported the highest rates of burnout. Similarly, Fattori et al.56 We observed that nurses and health assistants had a higher risk of scoring above the cutoff than physicians (OR = 4.72 and 6.76, respectively). Differences between the public and private healthcare sectors have also been previously analyzed. A recent study by Pavón Carrasco found that healthcare workers employed in public healthcare institutions were at greater risk of contracting COVID-19 during the first wave compared to healthcare workers in private healthcare institutions. Awareness is reported to be low.43. However, anxiety levels among publicly employed health workers were higher than those reported by privately employed health workers (more than 25% and approximately 20%, respectively).Both groups had high levels of anxiety, even though the private sector was not considered a front line.43.

Several limitations of our study should be considered. First, its cross-sectional design makes it impossible to infer causality of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare workers without similar information collected before the pandemic. It is also not possible to estimate the true scale of change in the mental health of healthcare workers. There is a high possibility of mental disorder. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that during the first wave of the pandemic, psychological support was provided on demand to professionals who volunteered it in hospitals. In addition, group interventions were conducted to reduce symptoms at onset. It would have been interesting to assess the impact of these interventions as protective factors. However, this lack of data introduces further limitations and potential biases.

Second, the response rate was lower than expected. It is possible that people with mental health problems were more willing to participate, or that stressed workers did not have the time to respond. However, weighted data attempts to counteract this limitation. Third, the ratings in this study were based on self-reports from health care professionals and not clinically diagnosed mental disorders. For this reason, we describe them as possible mental disorders.

Importantly, our approach has been used in most epidemiological studies, allowing comparison of results.21, 23, 57. A more detailed analysis of proximal factors would have been interesting to link possible mental disorders and pandemic-related stressors.

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, we found that during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care workers at this large Spanish university hospital were likely to suffer from depression, PTSD, panic attacks, and psychiatric disorders. We can confidently conclude that this shows a high prevalence. anxiety. Young people and people with lifelong mental health problems are more likely to experience mental health disorders.

Based on our results, it appears to be expected that there is a significant demand for mental health services among health care workers at this hospital that needs to be met. Our results, as well as others, highlight the importance of closely monitoring the psychological health of healthcare workers and facilitating their access to psychological support.

Understanding this data will help professionals who should be especially protected in high-stress situations to care for their mental health, such as workers with a history of mental health problems or other vulnerability factors. It also helps when choosing a profile.

Future research is needed to elucidate the evolution of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers over time in order to implement appropriate therapeutic interventions.